Youth Has Its Evening

"Interplay", "In the Night", "N.Y. Export: Opus Jazz"

New York City Ballet

David H. Koch Theater

February 5, 2019

Youth must be served, as the old saying goes, and no choreographer served youth as assiduously as Jerome Robbins. He admired the audacity of the young Twyla Tharp, using Central Park as a performance space, and was often the first to spot – and spotlight – young talent at the New York City Ballet, particularly among the male dancers. And, above all, youth and young people were a favorite subject of his ballets from "Fancy Free" on. Youth permeated this all-Robbins triple bill (filled with debuts), excessively so by the end of the evening.

Robbins was also a master of translating a moment in time from the street to the stage. For all its comic camaraderie, death trails the three sailors throughout "Fancy Free". "Interplay", the choreographer's second ballet, had its premiere less than a month after V-E. Day. It is full of youthful high spirits, playfulness, gentle romance and good-natured competition, particularly American in its invincible optimism. "Interplay" seems to reflect the national mood almost to a specific day. With his light, floating jump and pleasure at being in motion, Roman Mejia, easily caught the tone of the piece. In the virtuoso solo of 'Horseplay', Spartak Hoxha was more good-natured than showy, trying to coax the others into joining the fun rather than keeping it all for himself. Otherwise, this performance, while technically well danced, seemed dry, hard-edged and encased in a bubble. Have any of the dancers (particularly the women) ever been young or have they just been bunheads?

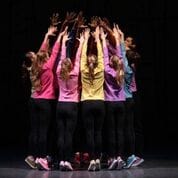

Like "Interplay", "N.Y. Export: Opus Jazz" finds Robbins reflecting the zeitgeist in the theater. But how times have changed. The year is 1958. The Cold War grinds on. Beatniks are the epitome of cool and television is in its infancy. (The opening backdrop, by Ben Shahn, is a traffic jam of antennae against a milky sky.) The setting is urban – up on the roof, at an outdoor basketball court. Yet here too, in a performance with debuts in all four leading roles, the men stood out more than the women. David Coll had the right spring to his step for the period and Peter Walker was both attractive and elusive in the pas de deux. When he walked off, leaving Laine Habony bereft in the dark, you knew why. But Gilbert Bolden III, in a corps role, connected most seamlessly with his inner hep cat.

"In the Night" examines the ages of love: young love, possibly quite new; youthful though experienced love; mature love as conflict. Her lightness and his unfailing courtesy (almost to the point of chivalry) and generosity as a partner, would seem to make Sterling Hyltin and Tyler Angle perfect in the duet for the youngest of the lovers. But both seemed too strong, too fully formed to convey the uncertainty of nascent attraction.

Robbins once told Philip Neal that the middle duet was about a husband and wife reunited after a long separation. Their duet is usually formal, reticent, restrained, perhaps, given Robbins' narrative, the first steps toward mutual rediscovery. Sara Mearns, her jaw slightly forward, ready to bite, her eyes blazing like torches, was having none of it. Her rage at her spouse was all-consuming, whether because he had left her or because he had returned, unknown. Watching her, Ask la Cour (in another debut) seemed surprisingly relaxed, as though he'd seen it all before and knew that the flames would soon burn themselves out.

Distress of cosmic proportions is supposed to be the turf of the third, older couple. In her local debut in the part, Tiler Peck knew who she was and technically what to do. Yet everything was too small in scale. Her flailing arms were not those of a woman railing at fate but of a two year old in mid-tantrum. The stage should be too small to accommodate all her pent up resentments. If Peck can ramp it up without losing clarity and precision, she'll be unstoppable.

Beyond debuts, this triple bill brings up questions about coaching and programming. It is impossible to turn back the clock to 1945 or 1958. But what can be done to meet this dances, if not on their own turf, part way there? The original program note for "N.Y. Export: Opus Jazz" mentions contemporary popular dance at some length. Did that ever come up in rehearsal? Also, while technically sleek in execution, in both "Interplay" and "N.Y. Export: Opus Jazz" Robbins is given short shrift as a man of the theater. If this can't be fixed, the ballets are in danger.

An all-Robbins evening is admittedly difficult to program. By my count, he made one large scale send 'em home happy piece ("The Four Seasons"). But most of his works are chamber sized. Even so, it should have been obvious that "Interplay" and "N.Y. Export: Opus Jazz" are too similar to share the same bill. Peter Walker is an interesting dancer, but should he really have appeared twice in one night as the male half of a pas de deux, both times in a blue shirt?

copyright © 2019 by Carol Pardo