White as Snow, with Shades of Darkness

“Snow White”

Ballet Preljocaj

David H. Koch Theater

New York, NY

April 25, 2014

Snow White’s hair wasn’t the only thing black as night in Angelin Preljocaj’s balletic take on Brothers Grimm’s fairy tale. – The entire ballet, from set design to the story, was cast in darkness. The stark departure from the colorful and cute Walt Disney version was intentional, but paradoxically, by removing all things Disney and kid-friendly, Preljocaj made this “Snow White” more magical.

The work stood out on two counts: as a narrative ballet based on a fairy tale yet with deeply adult themes, and by being a work of visual art as much as a dance. The performance ran for close to two hours without intermission, which tested viewers’ stamina but also helped maintain continuity. The unremitting presentation built the story’s intensity to the culminating finale where, true to original text, the evil Queen was brutally punished by having her feet placed into shoes filled with burning coals and forced to dance to her death.

The masterful use of artistic elements embellished the very Grimm narrative of this production. Thierry Leproust’s dark set designs made the costumes and performers pop in contrast. An emotional and mysterious musical accompaniment pieced together from Gustav Mahler’s symphonies and interspersed with modern sound effects supplied romance as well as sorcery. Preljocaj’s choreography freed the dancers and fashion’s enfant terrible Jean Paul Gaultier’s costume designs provided the sartorial edge. The final product was a perfect fusion of these elements and grounded the ballet in reality, while keeping it mysterious enough to maintain the surreal fairy tale qualities.

Preljocaj’s choreography intentionally wasn’t neat and avoided precise positions, so that sometimes the steps looked improvised. He included several scenes where the dancers would vocalize along with some of their steps by singing or grunting, which made them look even more at ease in their movements. The effect was compelling: the dancers looked as if each move was just another phrase of an ongoing dialogue in their native language.

Nagisa Shirai, who danced the title role, was the most eloquent in her expressions. Each of her steps had a purpose; some she performed carefully, with seeming thoughtfulness, others with spontaneity, and this approach slowly but generously revealed the mysteries of her persona. Her face projected coexisting wisdom and innocence.

As the Queen, Anna Tatarova’s total blackness of dress and spirit contrasted the pure white innocence in Shirai. It also colored the perspective Preljocaj gave on the Queen’s obsessive resistance to aging and jealousy of her young step-daughter, even as he attempted to explain why growing old was so terrifying.

At first, it was difficult to understand why the subdued and mysterious purity of Snow White would distress the Queen so much. After all, she was a flashier, shinier woman compared to Shirai. But that was precisely it: the Queen was trying too hard and knew it. True beauty is effortless.

Youth and beauty were the key to the Queen’s powers, and it seemed that it was seductive powers of beauty, rather than beauty itself, that was so important. She first appeared during a ball, in black thigh-high stockings, spiky heels, and a bondage-inspired corset and made a point of directing her enticements at everyone, including the Prince who by then was courting Snow White (in Preljocaj’s tale, we meet him from the beginning). You couldn’t help but notice hints of growing desperation in these aggressive attempts.

The iconic mirror scenes were where the Queen’s self-indulgence reached its expressive peak. Facing a giant black mirror in a golden frame, Tatarova managed to fill it with the sheer scale of her self-absorption as she sashayed back and forth in front of it, sticking her hip out, thrusting her shoulder forward, loving what she saw. Sharing these scenes were her two black cats, performed by Caroline Jaubert and Margeaux Coucharrière, who seldom left Tatarova’s feet during the ballet. Besides admiring their mistress, they shared her narcissistic qualities.

But the ballet’s most captivating moments were the more innocent duets between Snow White and the Prince. There was the first interaction during the ball at the beginning of the ballet when the Prince, danced by Sergio Diaz, first sees Snow White and starts to court her. Preljocaj had the young couple mirror each other as they danced. Unlike the Queen’s mirror; their eyes were clouded not by self-love, but budding love itself.

The young pair encountered one another again in the forest. Starting in silence, Shirai and Diaz danced with so much emotion that it seemed all the better there was no music to interrupt it. The passage ended with the Prince holding Snow White’s right leg by the ankle, as she leaned and bent all the way to the left away from him, completely unbalanced by their interaction. The whole dance sequence repeated again, this time with music, and looked even richer the second time around, the notes adding depth to what we saw in silence.

Loss followed love quickly. The Prince’s next dance, to the adagietto from Mahler’s Symphony No. 5, was with Snow White’s dead body. Before embracing Shirai, Diaz dropped to his knees in grief. He crawled towards her, stood up and covered his face, punctuating his restless body waves and reaches toward Shirai with longing glances. Diaz made each movement echo with an invisible pull toward her and grief-stricken apprehension. Finally next to Shirai, he buried his face in her body and tenderly maneuvered her on stage, constantly seeking to make eye contact with her. Although Shirai’s body remained limp, she had the same fluidity as in her earlier dancing. It seemed even in death she was in harmony with Diaz.

The duet was as pure and beautiful as the murder scene that rendered Snow White lifeless was cruel. The Queen, after a very detailed and ritualistic disguising, lured Snow White with the poisoned apple, but it wasn’t trickery that got Snow White to bite. The magical fruit drew the heroine to follow it with unseen powers, holding her captive with growing intensity. In her jealous quest the Queen forced the fruit in Snow White’s mouth, smothering the girl with it, and proceeded to manipulate her body, shoving her down to the floor, then lifting her up and bending her like a rag doll. When she was done and Shirai’s body fell lifelessly to ground, Tatarova sat atop her victim in sadistic triumph, and then walked arrogantly offstage.

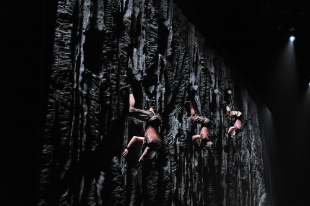

Absent from the title, and most of its storyline were the dwarves, but the few times they appeared they made a lasting impression. To enter, they crawled out of holes in a rock wall at the back of the stage. They appeared suspended, and proceeded to dance against the wall to the third movement from Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 in D with remarkable acrobatic skill. The scene could have rivaled any Cirque de Soleil performance. Their gravity-defying movements were so light and effortless that it was difficult to believe these aerialists were in fact meant to be underground mine workers.

This wasn’t the only time Preljocaj suspended his dancers in the air. In a scene that followed Snow White’s murder, her own deceased mother floated onto the stage, descending and kneeling at her daughter’s body, lifting it up, with the mother and daughter vertically inverted, floating connected and suspended in near-darkness. It was an eerie scene, but like many of Preljocaj’s creations added to the surreal qualities of the ballet.

Despite the work’s dark dominant color and sobering story, it remained a fairy tale complete with a happy ending. The otherworldly effects, as well as the love story, softened the treatment of the ballet’s brutal plot, and made you walk away thinking this “Snow White” may well be the fairest of them all.

copyright © 2014 by Marianne Adams