The Legat Legacy

"The Legat Legacy" edited by Mindy Aloff.

University Press of Florida, 2020.

With its rich list of books on dance history, technique and memoirs, The University Press of Florida has become the go to publisher for dance books. This recent work, a reprinting of the 1939 "Ballet Russe: Memoirs of Nicolas Legat" and the 1977 "Heritage of a Ballet Master: Nicolas Legat" under the title "The Legat Legacy" is a welcome addition.

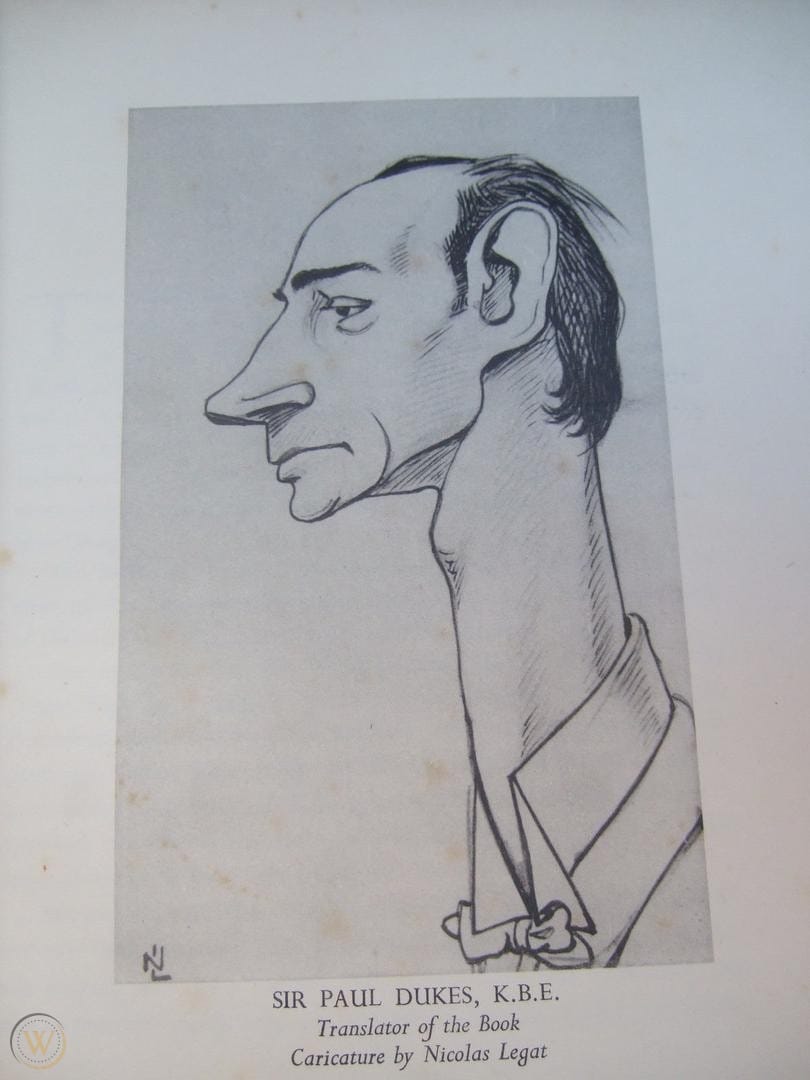

His memoirs were written in Russian; though he taught in England from 1926 until his death in 1937, he never learned English. The translator, Sir Paul Dukes (oddly called Sir John Dukes on the title page verso) was the perfect translator. He had studied music in pre-war St. Petersburg and had seen Legat on the Mariinsky stage. His Russian was so good that, while working for MI6 after the Russian Revolution, he was able to pass as a native (even joining the secret police at one point) and he was a vivid and gripping writer, as his own memoirs show. He was also closely connected to the British ballet scene, as his brother Ashley Dukes was married to Marie Rambert.

Nicolas Legat (1869-1937) was born into a theatrical family. His father Gustav, who was one of his teachers, studied with Petipa and worked at both the Mariinsky and the Bolshoi. He also studies with Pavel Gerdt, and especially Christian Johansson, the Danish trained (by Bournonville, father and son) dancer and teacher, whose class of perfection Legat assumed on Johansson's retirement. Legat's memories are warm and generous, writing of Johansson as a "benevolent old sorcerer" with "his magic violin wand." (The venerable teacher gave his violin to his successor, which unfortunately was destroyed in the revolution.)

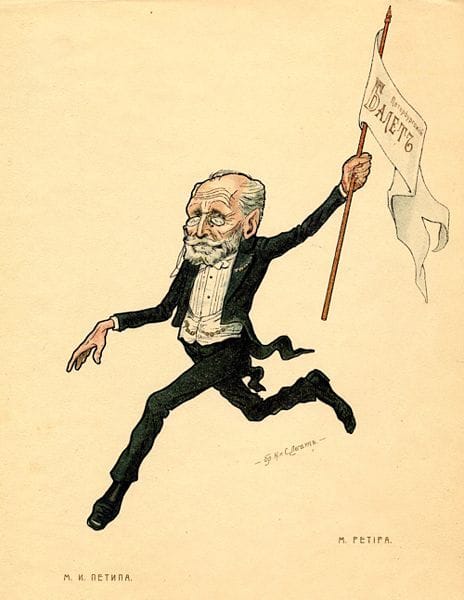

He also writes fondly of Petipa, "the life and soul of every gathering, [who] kept things always on the go by his stories, jokes, and juggling abilities." He is perceptive and generous about the influx of Italian dancers and his excitement at their astounding technique (thirty-two fouettés included) is so vivid. It certainly spurred the Russians, and Legat writes about carefully observing Legnani and working with Kshesinskaya. The day after Kshesinskaya first performed them, he writes "I received a gift of a gold cigar-case and a note of grateful thanks for a certain very exalted personage."

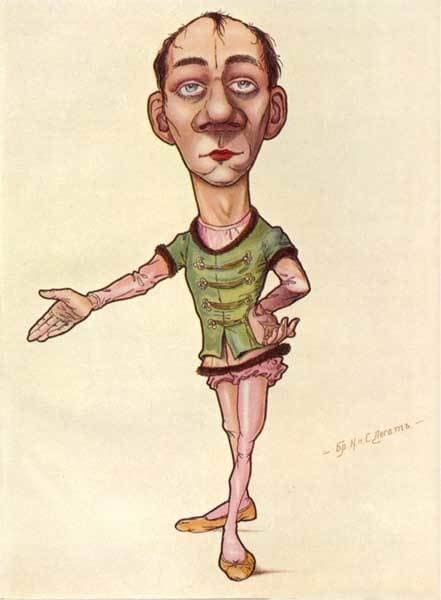

Legat was also a talented caricaturist and the book has a generous sampling of them. The original 1939 memoirs reproduced them in color, but as Aloff's preface explains, modern publishers cannot afford such luxury. However, the reproductions are large and clear, and their wit (Kshesinskaya with her goat, a skeletal Pavlova wafting a scarf, Dolin with his muscles, de Valois running) are irresistible.

The second half of the book "Heritage of a Ballet Master", was compiled in 1977 by the writer, dancer, and teacher John Gregory, with André Eglevsky, and is a collection of reminiscences by some dancers and students who studied with him in England. One of the most famous, Eglevsky, was sent by Massine (who, Eglevsky writes, "was perhaps the most ardent student of us all"). Eglevksy credits Legat with giving him his pirouettes, and writes that thanks to that he was able to eat when he came to the U.S. "To ensure that I would be able to buy my lunch, I used to wager Mr. Balanchine I would turn twelve pirouettes for him. I never went hungry."

Some of the reminiscences are detailed (Alan Carter's and Wendy Toye's in particular) and some are brief (Ashton rather ruefully writes "He was undoubtedly a great teacher but I was too inexperienced at the time to get the full benefit of his great knowledge"), but all describe a dedicated, creative teacher. The book ends with four classes that Legat gave to Eglevsky, a gold mine, I expect, for teachers, but the greatest gift is the ability to spend some time with a teacher who so loves his subject.

copyright © 2020 by Mary Cargill