School Figures

"Square Dance", "Harlequinade"

New York City Ballet

David H. Koch Theater

New York, NY

February 25, 2015

by Mary Cargill

copyright © 2015 by Mary Cargill

"Square Dance", Balanchine's witty salute to American folk dancing by way of European courts, is a dance of crisp and gracious symmetry gilding a warm center. Erica Pereira, who danced the lead in the 2006 SAB performance, made her debut with the grownups. Her SAB version was meticulous, precise and uninflected, adjectives which, unfortunately, applied to her debut. She had an air of wispy eagerness and tended to give the steps the same emphasis, so that little insouciant leg flicks were delivered as strongly as the gargouillades. Technically she had few problems and the final footwork series was clear and sharp, but her dancing was one-dimensional and, with only a few glimpses at her partner, directed straight to the audience, like a student reciting lines.

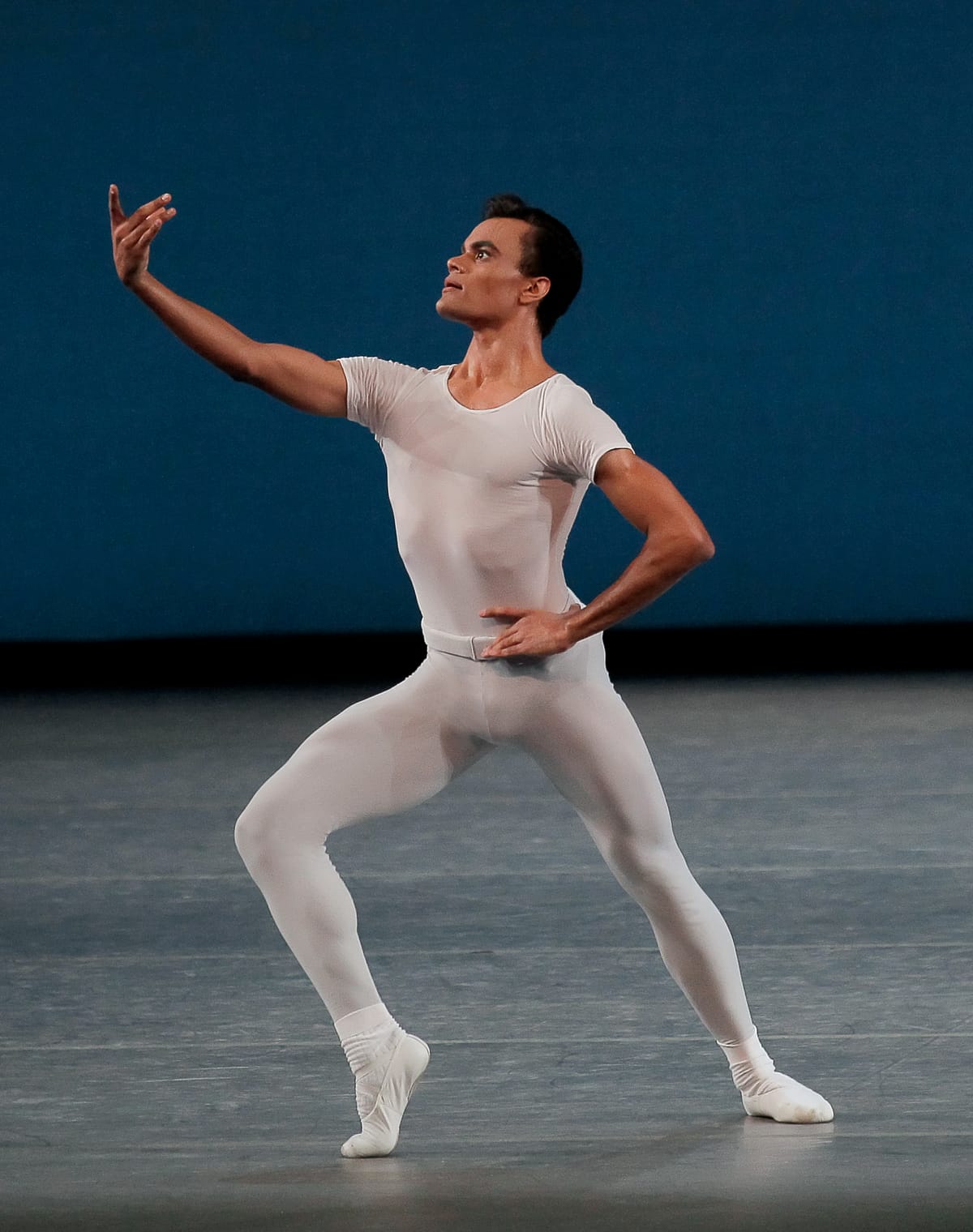

Her partner, Taylor Stanley, was well worth looking at. He used his molten fluidity so expressively, leading the group with lighthearted joy at one moment and then wandering through the music of the male solo Balanchine added in 1976 for the unique talents of Bart Cook. He seemed to dance this in one breath, with his arms continuing movements originating from his back (or even his soul), as he reached out into space for whatever it is poets fail to get. It was breathtakingly beautiful.

Anthony Huxley, Pereira's partner in the 2006 "Square Dance", also got a debut, dancing the hapless, white-faced Pierrot in "Harlequinade", Balanchine's take on the Petipa ballet "Les Millions d'Harlequin" based on characters from the commedia dell'arte; Balanchine had danced in the Petipa ballet as a child and the second act is chock full of children.

This performance was also chock full of debuts: every main character was having a first crack at their role, with varying degrees of success. Fortunately, the main characters, Columbine (Ashley Bouder) and Harlequin (Gonzalo Garcia) were both successful, technically and dramatically. The slight story (poor man wants to marry daughter whose father has a rich, foppish suitor in mind for her) is certainly familiar comedy fodder, but love thwarted and then rewarded has lots of excuses for dancing.

Garcia used his back beautifully in the opening serenade, echoing the Italian lilt to show a love sick suitor; it is of course difficult to know where Petipa ends and Balanchine begins, but Harlequin's demi-caractère strumming of his mandolin seems to foreshadow Apollo's lute. Garcia was a lovable scamp, transforming into a majestic partner (with a few Harlequin poses for accent) in the rigorously classical final pas de deux; it does seem to be one of Balanchine's jokes that two of the most traditional pas de deux he did (this one and the pas de deux from "Stars and Stripes") are danced by men wearing funny clothes.

Columbine gets to wear a traditional tutu, and Bouder wore it well, especially in her final dance, where her deep back bends seemed to sum up her awe and happiness; she gave the quick little steps an intensely feminine flavor and seemed to luxuriate in the choreography. As always, she seemed to be able to pause the music at the top of a move, freezing the picture of a perfect shape while having fun. Huxley, too, captured the character of Pierrot, as he flopped helplessly in his long white tunic. As Pierrette, his wife, the young corps dancer Clair van Enck showed off her long legs and pretty face, but was a bit bland; it was hard to realize that this character had entertained Europe for two hundred years. Isabella LaFreniere, another corps dancer, made her debut as La Bonne Fée, the good fairy that provides Harlequin with his gold. (Older comedies are quite clear-eyed about the value of money and there was no sentimentality about love in a garret.) She is a tall, luxurious dancer, but as yet a bit blank, and there was no sense that she is the Lilac Fairy's cousin; this was a demonstration and not a performance. Aaron Sanz, yet another corps dancer, made his debut in the mimed role of the pot-bellied Léandre, a role which makes Don Quixote's Gamache seem subtle. But Sanz, even in the over-sized Napoleonic hat, managed to give him some sweetness and pathos, using his long legs to suggest an over-eager stork, and elevating the ballet from the class room to the theater.

copyright © 2015 by Mary Cargill