Pretext, Subtext, Steptext

“Sarabande,” “Sunshine,” “Steptext”

Lyon Opera Ballet

The Joyce Theater

New York, NY

April 29, 2015

All three of Lyon Opera Ballet’s works on its opening night program focused on reconstructing and extracting from the grammar of the choreographic text varying meanings, and all three conveyed a perspective on modern choreography and a statement about the company.

The all-male “Sarabande,” Benjamin Millepied’s sequential approach to Bach’s music inspired by Jerome Robbins’s “A Suite of Dances,” presented an interplay of music and steps, with many of the body waves and patterns in the dance taking their cues from the sound waves of the live solos performed by the violinist Tim Fain and flutist Stefan Hoskuldsson. The music served as the pretext to the movement, and the four dancers throughout the ballet took the structured musical passages as their opening lines but then conveyed unexpected and at times more nuanced expressions, often pausing to wait for the accompaniment to introduce the next steps and their points of departure in the choreography. But while almost all of the solos exhibited this interplay with the music, the interactive sequences for two or more men instead worked to illustrate the musical texture beneath the melody through the symmetry of the coming together and apart of these dancers.

Lyon Opera Ballet’s “Sarabande” looked natural and intuitive, almost improvised in its expression but with sufficient exhibition of pre-conceived bravura in the solos. This was particularly evident in the dancers’ relationships with verticality, which in Millepied’s prescription here is either adhered to strictly, with movements performed in strict parallel alignment to the ground with little deviation, or expertly evaded, such as in the tours en l’air where the jumps are performed with rotation on a displaced axis, somewhat angled against the floor, and which the dancers approached with freedom but also distilled control. Even if not all technical elements were perfect, such as some grande jetés which looked constrained, the foursome made up for it with their remarkable ability to have their movements both complete and contradict the musicians’ sentences.

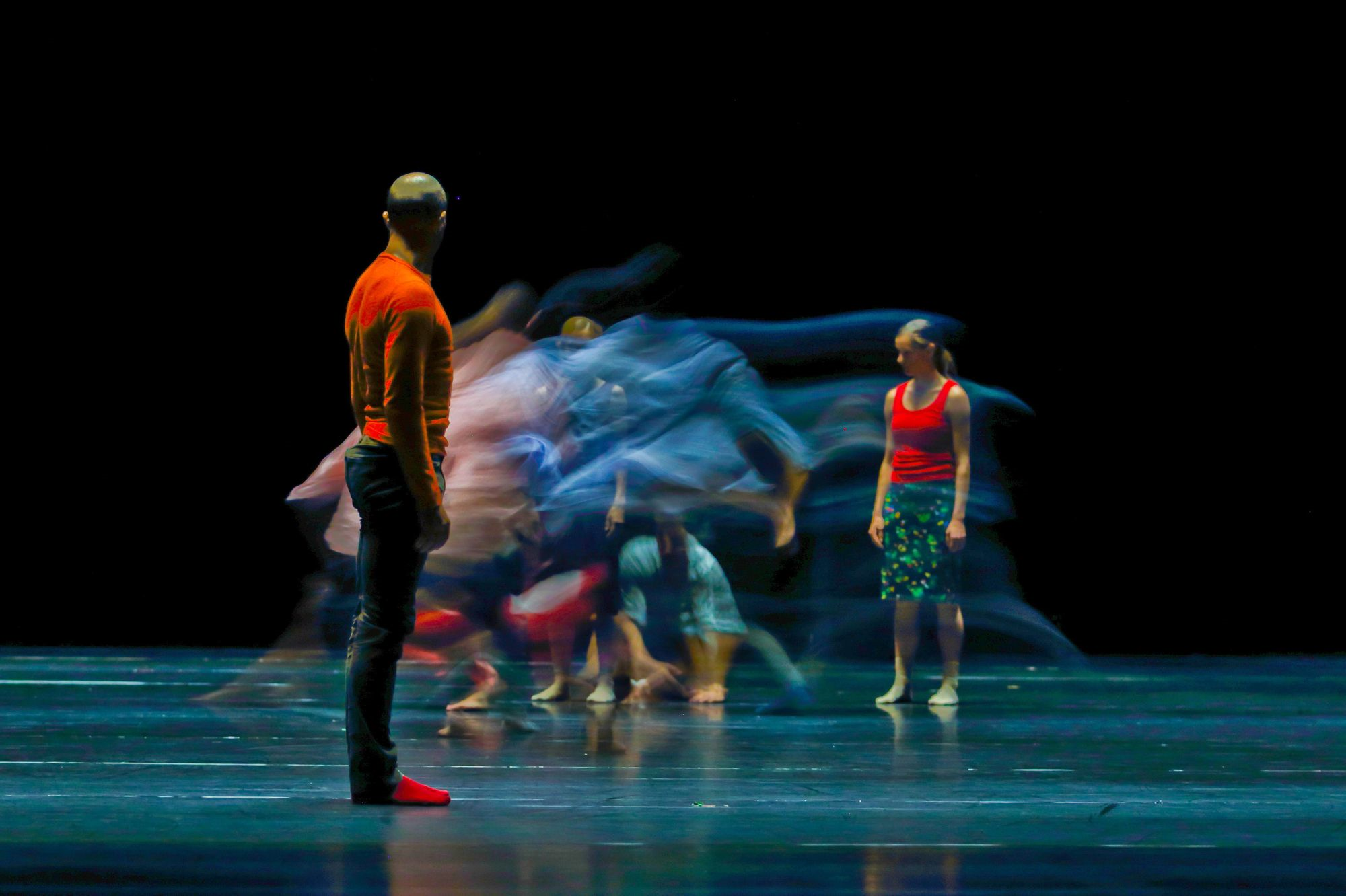

Emanuel Gat’s 2014 “Sunshine,” created specifically for Lyon Opera Ballet and appearing before the New York audiences for the first time, was a curious amalgamation of different movements and untold moments, with the choreography composed of numerous configurations, intertwining forms that were connected if not directly then by some common thread of searching emotion and arrested sequences where not much happened as dancers simply observed each other.

Gat’s array of steps ranged from walking, crawling and jumps to liquid transitions from one loose and undefined body form to another. This lack of apparent structure, combined with equally uncommitted accompaniment consisting of some passages from Georg Handel’s “Water Music,” but also whispers, sound of closing zippers, warming up orchestra, and talking voiceover sequences all taken from recordings of the Orchestra of the Opera de Lyon’s rehearsal of Handel’s music piece, all contributed to the work’s relaxed nature, where the piece invited you to watch it, but without any exertion or sense of commitment. Somehow, it was sound, not music, that was the accompaniment in Gat’s ballet, and its random feel bled into the nature of the dance, with variations in volume reflected in the dancers’ position on the stage – towards the back for lower volume and the front for the louder bits.

By Gat’s own account, the music isn’t key to his choreography, and the recording to which the company performed was mixed and added to the piece just a few nights before the work’s world premiere, at the end of the creative process. Odd as it sounds, this approach seemed to have forced the steps and not the music to be the ballet’s backbone, which was perhaps the key to making the dancers’ performance in the piece look the way it did -- semi-improvised, uniquely personal, and somehow still in formation. This late integration of music is also perhaps what accounts for the perceivable, though perhaps not articulable, common thread in the work, as the dancers seemed to have anchored their emotional meaning of the work in something internal, rather than music. The ballet may not have read like a masterpiece, but it definitely made for an fascinating 25 minutes.

“Steptext,” one of William Forsythe’s most widely performed works, closed the night, but despite being in this company’s repertory since a mere two years after its creation in 1985 it was the work the company seemed least comfortable in. This Forsythe ballet focused on reconfiguring the role of the woman in dance partnership and spelling out the dance with steps, like so much of his choreography, requires impeccable athleticism and control, and effortless flexibility. Although the company’s four dancers -- Ashley Wright, Raul Serrano Nunez, Marco Merenda and Roylan Ramos -- certainly possessed these qualities, they manifested them in erroneous ways. Where the steps required amplitude in extensions, the dancers, particularly Wright, exhibited control, and when the movement skewed off-balance in those signature Forsythe ways, the bends and curves in the dancers’ hips and lower backs, as well as lack of suspension in the pauses, often contradicted the intended phrasing. As a result, the choreography's frequently recurring off-balance line that makes Forsythe so difficult to dance and so remarkable to watch was wholly distorted, and with it the impression of work.

With that, the overall context of Lyon Opera Ballet’s presentation showed that while the company is determined to move forward with new choreography, its treatment of modern classics is far less apt.

copyright © 2015 by Marianne Adams