Old and New

"Cave of the Heart", "From the Grammar of Dreams", "Lamentation Variations" "Variations of Angels (Film)", "Diversion of Angels"

Martha Graham Contemporary Dance

The Joyce Theater

New York, New York

February 27, 20013

The current Graham season at the Joyce is called "Myth and Transformation", Graham presumably being the myth, and the new dances the transformation. "Regeneration" should also be acknowledged, as the beleaguered company struggled to cope with the damage from Hurricane Sandy. The opening myth, "Cave of the Heart", Graham's compact and powerful retelling of the Medea story got a graceful introduction by company director Janet Eilber, who briefly described the action. (Presumably, when Graham choreographed it in 1946, the audience would have been better versed in the classics.)

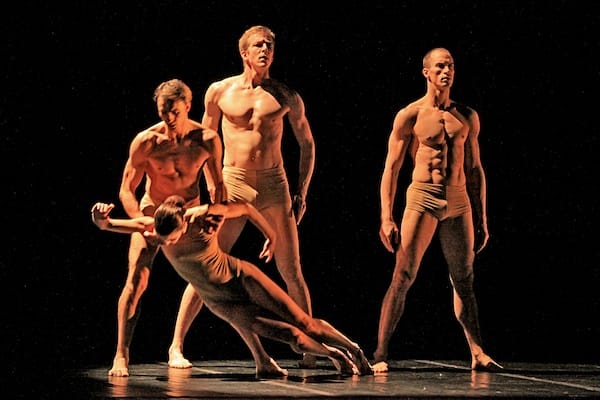

Miki Orihara as Medea was concentrated, desperate fury, and even her curling toes seemed ominous. There was no attempt to soften her crime or even to explain it, no forgiveness or understanding was possible in this bleak world. This dark impassiveness was heightened by Graham's theatrical savvy, knowing when to pull back and let the audience imagination do the work, as she avoided the obvious horror of presenting dead children. Instead, she has Medea pull a red ribbon from her dress as she curls up in agony, a reference, it seems to me, to both the pain of childbirth and the crime she is to commit. Iris Florentiny as the Princess who replaced Medea danced with an innocent and graceful sensuality that heightened the tragedy. Tadej Brdnik's Jason had to fight the Corinthian stud-muffin costume, which must have been impressive in the 1940's; now it looks like a fancy underwear ad. His dancing was powerful but the sweaty realism of the choreography isn't on a par with the oblique, allusive poetry of the women's roles. But despite the period flavor, the final moments, with Medea trapped in Noguchi's shimmering metal tree, are absolutely shattering.

Graham's 1930 solo "Lamentation" was the basis for the second work, as three choreographers (Bulareyaung Pargarlava, Yvonne Rainer, and Doug Varone) worked with elements from that work. Pargarlava's opened the variations, following a filmed version of Graham talking about the original. Her comments, modest and moving, described the effect her solo had had on one woman who's son had recently died. This flowed into Pargarlava's work to a Mahler song from "Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen"; the piece was elegant and smooth, but as with many dances to great music, it seemed to add little to the original.

The Rainer variation, on the other hand, was neither elegant nor smooth. Katherine Crockett sat hunched on a bench, huddled in a T shirt (presumably a reference to the original "Lamentation" costume, which another woman (Janet Eilber) shredded paper. Crockett then pulled a long piece of purple net through her T shirt in what looked like a parody of Medea's red ribbon. It ended with a jokey wave to the audience by Crockett; the program notes say that the "Lamentation Variations" was intended to commemorate the September 11 attacks, which made this postmodern nonchalance even more trivial. Doug Varone used "Lamentation's" bench to fine effect, as a support, a barrier, a lifeboat for four men, who made constantly shifting patterns, lifting and falling.

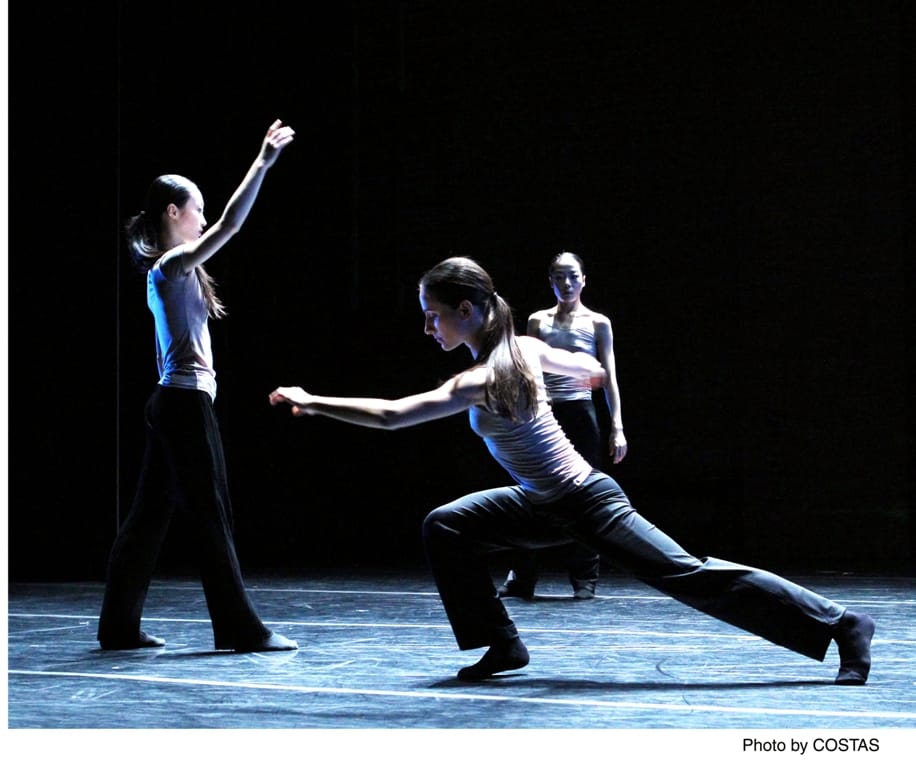

Eilber introduced Luca Veggetti's "From the Grammar of Dreams" by alluding to the Sandy destruction and saying that he had given his work to them as a gesture of support. But unfortunately generosity is not the same as quality, and the work, an examination of the non-linearity of dreams, proves that other people's dreams are of interest to no one else. The music (by Kaija Saariaho) consisted of breathy shrieks (quoting unintelligibly from Sylvia Plath), the lighting was the ubiquitous gloom with pools of light, and the very fine dancers (all women) took turns bursting into shards of movement. It had impressive moments but didn't add up to much.

Graham's 1948 "Diversion of Angels" does add up to a great deal. It was preceded by a montage by Peter Sparling, "Variations of Angels", which showed performances through the years, often superimposed on each other, so that the movements seemed to reverberate through time. Natasha Diamond-Walker, with Abdiel Jacobsen, was the woman in white gave a rich depth to her calm demeanor, as if she were looking back on her life. Blakeley White-McGuire had some rock-solid balances as the more dynamic woman in red, but I missed the slight air of danger some dancers give the role; she seemed to be more effervescently flirtatious than dangerous. (She does go off, briefly, with the white dancer's partner, after all.) Xiochuan Xie, with Lloyd Knight, as the woman in yellow, was a rousing bundle of joy, though there was a slight air of sadness, as if she knew that youth's joys could not last forever.

copyright © 2013 by Mary Cargill