Mountains and Valleys

"Beneath The Tides", "Solitude", "Mystic Familiar"

New York City Ballet

David H. Koch Theater

Lincoln Center

New York, New York

May 17, evening 2025

This program grouped three ballets choreographed in the last two years which pointed, presumably, to the future. Alexei Ratmansky, currently NYCB’s artist in residence, was the senior, with “Solitude” which was choreographed in 2024, while Caili Quan’s (“Beneath the Tides”) and Justin Peck’s (“Mystic Familiar”) works both premiered in 2025. It was a case, though, of older being better, and “Solitude” towered over the other two works like a mountain surrounded by valleys.

“Solitude”, dedicated to the children of the Ukraine, was inspired by a photograph of a Ukrainian father sitting beside his son who had been killed in the war. The ballet is both specific and universal in the same way that Antony Tudor’s shattering “Echoing of Trumpets”, which was inspired by the 1942 destruction of Lidice by the Germans. Both are powerfully restrained stylized laments that focus on ordinary people suffering unbearable loss, and which expand to mourn the horror and tragedy of war.

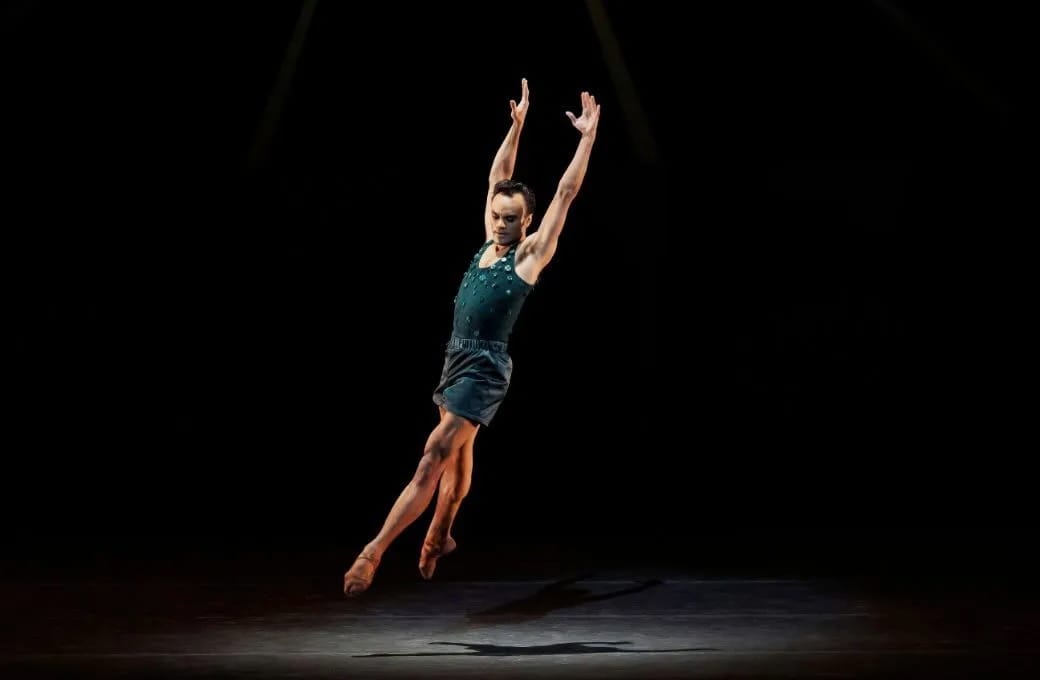

Ratmansky set his work to familiar excerpts from Gustav Mahler works, the Funeral March from Symphony #1 and the Adagietto from Symphony #5. The music swirled around the thirteen dancers as small groups entered in the dark, crawling, falling, supporting each other in uneasy, sharp moves while the lone man sat motionless by his son (Hannon Hatchett, an SAB student). Daniel Ulbricht made his debut as the father. He is of course renowned for his sharp and powerful jumps and is usually cast as a bouncing speed demon, though he is a powerfully dramatic Prodigal. His portrayal was less lyrical than Joseph Gordon’s, who originated the role; Ulbricht doesn’t have Gordon’s long line, but his he gave the off-centered arabesques of the long solo opening the second half a searing urgency.

He gave the simple gestures of the solo, standing up, turning, looking for his son, an honest naturalness, moving through the music as if it were part of him. He controlled his jumps so that his landings were completely silent, and it did seem as if he were living a memory. The final realization that he would never see his son alive again, as he resumed the opening pose with the boy lying beside him was almost unbearable. It is a staggering work and Ulbricht gave a powerful performance.

Justin Peck’s “Mystic Familiar” also has a long male solo (danced by Taylor Stanley), and unfortunately the work looked a bit thin coming right after “Solitude”. Peck seemed to be tempting fate by using the word “familiar” in the title, and many reviews have pointed out the many similarities between it and other Peck works. Balanchine, of course, reused many ideas, especially the lone poet looking for his soul mate, and the classical clarities of “The Sleeping Beauty”, but his ballets make is clear that there was more to explore. “Mystic Familiar” seems like Peck is just repeating himself, letting his dancers prance around in sneakers yet again with an “I’m young and cool” air.

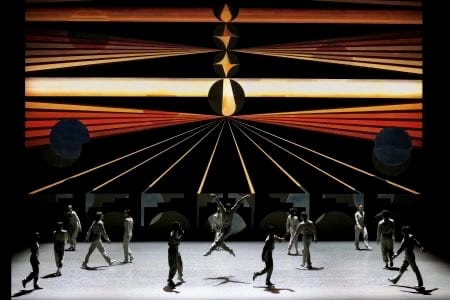

There were five brief sections (Air, Earth, Fire, Water, and Ether), a colorful geometric backdrop by Eamon Ore-Giron, lots of costumes by Humberto Leon, and music by Dan Deacon which was lively in a throbbing Philip Glass style. Peck arranged his 14 dancers in his familiar forms—clumps which opened out to circles and semi—circles and dancers in straight lines leaning sideways. Stanley’s Earth had a squiggly solo, full of repetitive arm waving, which he danced with his usual intense concentration. Peter Walker, too, as Fire (in a bright pink jumpsuit) danced with a loose-limbed enthusiasm, and the corps exploded in the final Ether, dressed in white. They did have to listen to some rather pop psychology as the lyrics explained that “The time is right here, right now. Become a mountain, remain a mountain”. Next to “Solitude” “Mystic Familiar” was just a shallow dip next to a real mountain.

The opening ballet, Caili Quan’s “Beneath the Tides” also remained in the shallows. She danced with BalletX and is currently a free-lance choreographer who has made works for a number of companies. The rather opaquely titled “Beneath the Tides” (it seemed to be set in a ballroom, with no water in sight) was set to Camille Saint-Saëns “Cello Concerto No. 1”, music which was not written with dance in mind, and which seemed to disappear among the swirling dancers. Gilles Mendel dressed these swirling dancers in an odd combination of elegance and tackiness. The men, especially, looked disjointed in their trim black tights, fancy waist clinchers, and bare torsos. The women’s chiffon dresses, though, were elegant, if a bit too long, and their bare legs, looking pale and wobbly, were distracting.

The choreography was a bit rote—loud music meant lots of dancers on stage, and the quiet bits were for duets and solos, with little real interaction or connection. The choreography was a somewhat uneasy mixture of stately classicism (there were lots of courtly bows), and modern signifiers (flexed feet, head swirls, snaky arms). The dancers, though, were immensely watchable, especially Jules Mabie and Aarón Sanz showing off their gorgeous lines in their duets, especially their second one, where they seemed to twist over each other and Indiana Woodward pirouetting through the mass of dancers. Sara Mearns and Chun Wai Chan (in his debut) danced a pas de deux, alternately lyrical and dramatic; Mearns was hypnotic and Chan fluid and grounded, but the ballet’s drama seemed to come in fits and starts, with no connecting threads.

© 2025 Mary Cargill