Love, Lust and Power

“Spartacus”

Bolshoi Ballet

David H. Koch Theater

New York, NY

July 25, 2014

As a powerful, masculine and very adult ballet, Yuri Grigorovich’s Soviet-era choreographic chef d’oeuvre, “Spartacus,” is not what you are used to. From the moment the Bolshoi dancers first appeared as the charging Roman soldiers accompanied by Aram Khachaturyan’s commanding score, you were transported into a colorful presentation of a historical tale and a world dominated by a fervent fight for freedom and power.

The work, with its many novelties, forever changed the landscape of Russian ballet and Bolshoi repertory when it debuted in Moscow in 1968, becoming a sensation even before opening night and earning Grigorovich, and those in the two original casts, the highly prestigious Lenin prize. “Spartacus” stood out by being a daring and unconventional portrayal of romantic heroes that made classical dance its sole tool of expression and focused almost entirely on male dancing. Folding lyrical qualities into its epic narrative and presenting a corps-powered, testosterone-fueled, grandiose experience, the ballet is widely considered in Russia to be one of Grigorovich’s greatest achievements. Decades later, its novelties may seem dated today, but its merits remain.

The four soloists in the ballet, Spartacus, Crassus, Phrygia and Aegina, each represent radically different personalities and their respective heroics, domination, tenderness and seduction act as the four corners of the narrative, driving the story to a triumphant but tragic end. A rich portrayal from each is essential, and in the Bolshoi’s history remarkably few dancers have been selected to interpret these roles.

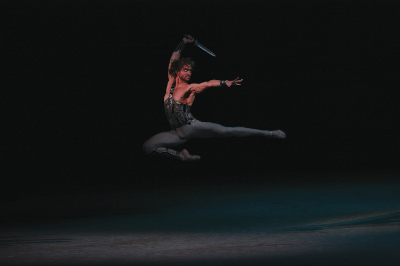

The cast in this performance did the ballet justice. Following the opening scenes that introduced the male-dominant features of the ballet, Mikhail Lobukhin, as Spartacus, wasted no time making a statement, emerging powerfully from the slave crowd for a dramatic solo. His tormented soliloquy after losing his freedom to the Romans presented one of the ballet’s calling cards – the choreographic monologues where the staging cuts away from the main narrative to leave the dancer alone to express his or her feelings.

Lobukhin’s first monologue was a hyper-masculine, rebellious statement against his situation. Although his arms were in chains, he swung them powerfully, creating the illusion of a sword tied between his hands. In other scenes he looked like a Vladimir Vasiliev doppelganger both in appearance (he even had the same choppy blond hair!) and the portrayal of Spartacus as a hopeful dreamer -- a welcome sight to those nostalgic for the legendary performer of the original cast. With his athletic jumps and fierce determination, he was a leader to rally behind, but with a sensitive side.

Alexander Volchkov’s vain and successful Crassus was Lobukhin’s opposite. He remained aloof when he wasn’t vaulting through the many powerful leaps that pepper the choreography. Still, the more cruel or indulgent scenes lacked the diabolical spark or ice-cold resignation that would have made him a better anti-hero. It was in the few scenes where Crassus has to show weakness that he was most effective: when he lost the one-on-one fight with Spartacus and was at the mercy of his enemy, his hysterical and desperate reaction, shakily gesturing “Go on, kill me!” let you feel his panic at such a humiliating defeat.

Of the women, the usually emotionally reserved Svetlana Zakharova exuded so much sensuality as the courtesan Aegina that every step and tilt of the shoulder subjugated those around her. Each of her appearances, even in non-dancing moments, signaled trouble – this seductress quickly gained control over those around her. Such an animated performance was an unexpected and welcome treat coming from Zakharova, whose famously extraordinary physical facility embellished the many extensions and attitude poses.

Aegina spearheads the uncharacteristically sensual elements of “Spartacus,” which were considered risqué enough to earn the ballet an over 16-only age restriction during the Soviet era. Some of Aegina’s moves in the Act 3 dance that spurs an orgy even had to be toned down at the Soviet reviewing committee’s request. The story goes that Grigorovich honored the request, instructing one of the two original Aeginas, Svetlana Adyrkhaeva, to remove certain elements for the first performance but revert back to original choreography after opening night. The Bolshoi performed that restored version and for contemporary times it may have seemed tame enough. Only the subtleties, requiring some imagination, hinted at what was deemed inappropriate for the Soviet youths. Gratuitous or not, it provided a reprieve from the energy-charged performances of the fight, power, and rebellion-focused themes.

Contrasting Zakharova’s Aegina, Anna Nikulina as Spartacus’s partner Phrygia delivered a tender performance, even if at times she looked too cautious. It was difficult to tell if the reservations in her dancing were part of her portrayal of the enslaved and isolated heroine, or actual discomfort on this stage. It looked most disappointing in the Act 3 solo she performed before the famous duet with Spartacus -- her tour lents and elevated rond de jambes were so careful that her focus on executing those simple moves pulled her out of her character.

Ultimately it almost did not matter, as Nikulina gained footing in her role in time to deliver an enrapturing performance in the famous adagio, punctuating the many accented lifts with broad movements. She effortlessly executed the acrobatic one-handed lift where she was carried by Lobukhin across the stage in a vertical split. The duet was full of innocent and hopeful love, and stood in stark contrast to Zakharova and Volchkov’s interactions. Their Act 2 duet arrived out of Aegina’s monologue about her goals of seducing Crassus, and was sexier, but also devoid of deeper emotion: more akin to a delectable business transaction.

Love versus lust, forgiveness versus revenge, subjugation versus freedom, the dancers presented each of these themes in a way that made it difficult to pick a side – you could understand the appeal of each. But in the end, Grigorovich leaves little doubt which he wants you to find winning, as Spartacus’s dead figure was lifted high by a dramatically lit group of dancers on a darkened stage for a sad but nonetheless triumphant finale.

The uniformly grandiose performance, from the leads to the corps, made the Koch Theater stage seem too small for this troupe. This “Spartacus” wasn’t just Bolshoi big – it had passion, power, and glory fit for the Romans.

copyright © 2014 by Marianne Adams