Lifar Lied to Himself?

"The Fascist Turn in the Dance of Serge Lifar"

by Mark Franko

Oxford University Press, UK, 2020

Before tackling this exhaustive and exhausting book about the controversial Serge Lifar by Mark Franko, who is a widely published critic and a professor at the University of California's Santa Cruz campus, I suggest that readers review what is generally known about Lifar (1905 - 1986) as a dancer, choreographer, company director, commentator on dance and as a person. I encountered Lifar directly in 1948, when he brought his Paris Opera Ballet to tour the USA. The company was large. Its training seemed admirably uniform. Stylistically, though, many Americans found the dancing "mannered". The choreography and dramaturgy, mostly by Lifar, seemed old fashioned compared to Antony Tudor's psychodramas or George Balanchine's neoclassicism.

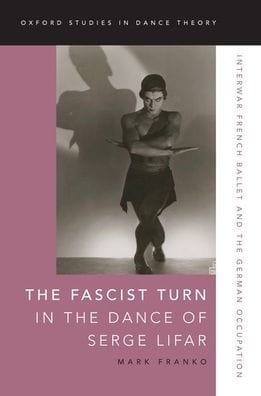

There is the evidence of still photos that Lifar was a strikingly sensual performer in his youth. He had studied in Kiev with Bronislava Nijinska, and in 1923 she funneled him to Diaghilev's itinerant Ballets Russes in Europe. Diaghilev sent Lifar to the Italian maestro, Enrico Cecchetti, for additional technical training. There is, supplemental to the still photos, a bit of film that shows Lifar in the 1920s dancing as continuously as our best male classicists do today. However, Lifar did not endure as elegantly as his similarly aged Diaghilev colleague, Anton Dolin. For the American tour In 1948, Lifar was past peak as a danseur noble. Also influencing the American public's response in 1948 was, of course, Lifar's reputation as a Nazi collaborator, even though he was defended by the Opera's prima ballerina, Yvette Chauvire. She stated that his actions during World War 2 had saved the lives of Opera employees who would otherwise have been on the Nazis' extermination list. Most of the Opera's dancers defended Lifar but most of the stagehands did not. All in all, Americans preferred the small, chic Ballet de Paris of Roland Petit, which toured North America not long after the Paris Opera Ballet.

My reason for calling the book exhaustive is that Franko seems scrupulously thorough in discussing those aspects of the Lifar phenomenon that interest him. The focus is very much on critics and their categories for classifying dance. Franko's discussions of the hide-and-seek games aestheticians play exhausted me. Definitions are crucial for Franko's interest. Not only what is fascism but what is fascist dance? Not only what is neoclassicism but what is neoclassical ballet? Undoubtedly, attention to these and related questions is necessary, but apparently for their sake Franko gives short shrift to the crucial task of comparing Lifar with other choreographers of relevance. How do Lifar's ballets rate when measured by the standards of choreography set by his major contemporaries and immediate predecessors - Fokine, Nijinska, Massine, Balanchine, Lander, Lavrovsky and even by Derra DeMoroda, who may not have been major but headed Kraft durch Freude / Force thru Joy, the official ballet company of Germany's Nazi party? (Ironically, DeMoroda may have been a major Allied spy in Germany during World War 2.) Franko's comparisons of choreographers in this book are few and rudimentary. His most valuable contribution in this regard is to point out that Balanchine's plotless "Le Palais de Cristal" (the Bizet "Symphony in C") in 1947 was prompted by Lifar's 1943 plotless "Suite en Blanc" (music by Lalo). That is a connection not mentioned by most American dance historians. It was Balanchine who had recommended Lifar to the Opera, and to the end of Balanchine's life he asked people returning to New York from a Paris visit what Lifar was up to.

With the death of Diaghilev in 1929, the Ballet Russe ceased to be. Its dancers scattered. Balanchine was engaged by the Paris Opera Ballet to choreograph Beethoven's "The Creatures of Prometheus" but became very ill and recommended Lifar as his replacement. Lifar was offered the directorship of the company, holding the position from 1930 to 1944, and again from 1947 to 1958. The reason for the gap in Lifar's directorship was that he was judged to have been a collaborator with the Nazis during World War 2 and was punished by dismissal. He worked with other ballet companies during his dismissal from the Opera. He retired in order not to be fired in 1958.

Critics who turn up in Franko's book include Akim Volynsky, Andre Levinson, Jean Cocteau, Lynn Garafola, Lincoln Kirstein, Paul Valery, Patrizia Veroli and many more. Some of the critics in France favored Lifar while others did not. Oddly, the anti-Lifar stance of Levinson switched to being pro-Lifar in Levinson's last book.

Fascist ideas about race, nationality and civil behavior appear in Lifar's dance writing prior to the Nazi occupation of Paris. Right after the start of the occupation, Lifar, although not overall director of the house, took the initiative of reopening the Opera and hosting the top Nazis. Of course, artistic directors everywhere tend to be dictatorial, but not necessarily racist. In his pronouncements on dance, Lifar praised Aryan order and damned especially Semitic chaos.

The information Franko gives about Diaghilev and Lifar makes me wonder whether both did not see Lifar's potential too much in terms of Nijinsky. Had the training and molding Lifar received turned him into an imitation Nijinsky rather than into an artist in his own right?

The softcover edition of this book of 277 pages sells for $39.95 at Amazon. Grainy black/white photos illustrate it. They serve in making particular points. For example, Photo 10 of Lucienne Lamballe and Lifar in his "Prometheus" shows her taut classicism vs. his loose cubism. (Erratum: in the caption for Photo 29 of Balanchine and his leading dancers for "Le Palais de Cristal", Micheline Bardin, ballerina for the pert 3d movement, is given an incorrect first name.)

copyright George Jackson 2020