Hidden in Plain Sound

Lincoln Center White Lights Festival

Thomas Adès: Concentric Paths – Movements in Music

“Outliers,” “Life Story,” “The Grit in the Oyster,” “Polaris”

New York City Center

New York, NY

November 20, 2015

The Thomas Adès program of the Lincoln Center White Lights Festival, offering four works by as many choreo-graphers to Adès’s music performed live with Adès himself behind the podium or piano for each, culminated in a riveting presentation of Crystal Pite’s 2014 ballet “Polaris,” but not in a build-up sort of a way. Instead, the first three ballets managed to conceal their substance behind their respective scores, tasking the viewer with the need to discern meanings that could have been more obvious through design or execution and required less viewer work. The ending piece was a worthy reward for such labors, but that’s also not to say that the journey to it through this Sadler’s Wells production was unenjoyable.

Wayne McGregor’s “Outliers,” a familiar ballet to New York audience from its premiere in 2010 at the hands, feet and bodies of the New York City Ballet, swirled to life on stage to begin the program and immediately proceeded to weave in and out of unexpected poses. The spirit of the ballet is free and misbehaving, like the Adès “Concentric Paths” violin concerto that accompanies it, though the execution by the dancers of Company Wayne McGregor gave it a different feel.

Compared to the originating NYCB cast, these dancers made the moves look less spontaneous and illustrative. The numerous athletic transitions in the work, designed on the technique-focused, less limber and more precise bodies of NYCB, here were missing the crisp geometry in the circular movements due to a lack of grounding strength. Similarly, the more fluid transitions from balances to supported turns that prevail in the choreography felt less instinctive, more labored and also lacking in control and awareness. The ballet may be designed to showcase the boundless and unanchored spirit of the score, but here it looked free-flowing rather than free. While the work’s kaleidoscopic action of differently paced scenes was presented with enough visual cohesion to hold the viewer’s attention, it took the whole ballet to figure out that what kept it from really resonating was the missing execution and delivery structure endemic to NYCB.

The program shifted to lighter notes after an unnecessarily lengthy intermission with “Life Story,” a 1999 work by Karole Armitage set to Adès’s 1994 music and integrating Tennessee Williams’s poem by the same title, which was sung humorously by Anna Dennis. The ballet and the poem capture the odd time between two people at the end of a one night stand, and the dancers, Ruka Hatua-Saar and Emily Wagner, in various forms of undress, painted it with abundant awkwardness and physical objectification.

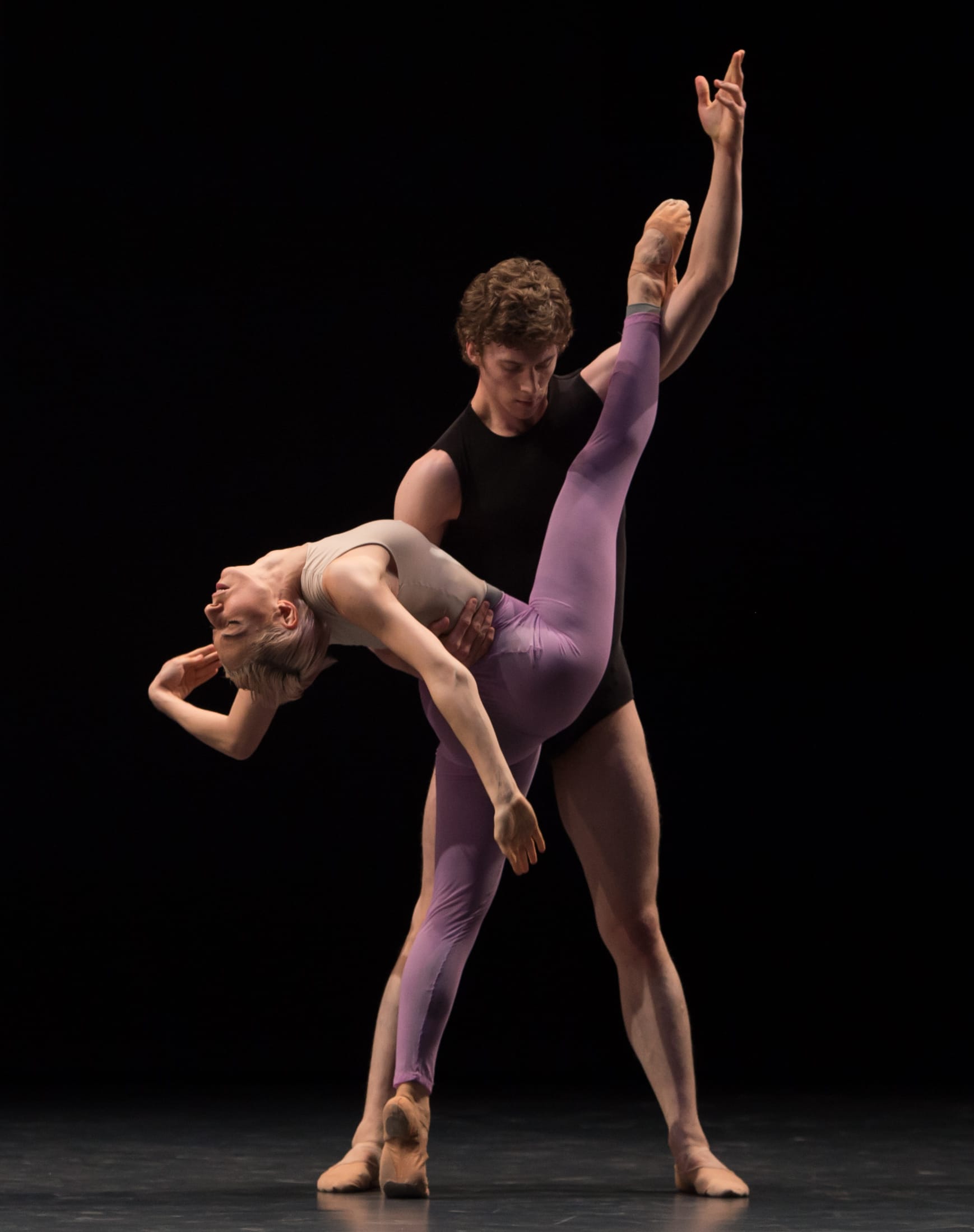

The jagged and somewhat uncomfortable juxtaposition of the music’s abrupt chords with the singing of the poem gave the work an abstract feel, both capturing and highlighting the awkwardness of the depicted interactions. The dancing, with its many lifts (often in splits), intertwinements and body releases, with the dancers periodically slumping in each other’s arms like rag dolls, displayed a closeness without intimacy, and a physical interaction with singular resolve and little warmth. The ballet was both humorous and sad in its emotionally divorced interfacing, with the words of the song frequently coming to aid in making sense of it all, until the dancers’ ultimate release from the situation where they pirouetted offstage in different directions.

Alexander Whitley’s 2014 ballet “The Grit in the Oyster,” to “Piano Quintet,” followed, and set itself up to appear as intriguing as its title suggested. Three dancers, Natalie Allen, Antonette Dayrit and Wayne Parsons, dressed in contemporary multicolored clothing, interacted throughout the ballet, dancing alternatively alone, all together, and partnered in short duets with the third dancer watching. The architecture of the choreography was varied, at times filling the music with nuanced and energetic movement, at other times locking the dancers in interconnected poses and letting the music play on – ceding center stage to the sound. There was a recurring move that tied the work together, a grand rond de jambe in which the body then followed the leg’s trajectory, turning and then collapsing to the floor or continuing under the outstretched arms of a partner, thus breaking or reforging partnerships. Its overall effect and the choreography as a whole resembled morphing play-dough, with the dancers’ dynamic and shapes looking composed in one moment, disintegrated in the next, and then formed into something different. The interactions maintained a discernible tension between cohesion and counter-position, but ultimately not enough to produce their pearl.

“Polaris” was another story. The ballet didn’t seek to make a grand entrance, but in the slow, self-assured seeping of the 66 cast members, which included a number of NYU Tisch School students, in identical black costumes from stage left it was impactful even before the first music notes. With the cast fully onstage, and thanks to the strange smoky looking backdrop that said little but somehow gave context to the movement (and then, through change of lighting appeared to change in texture), the dancers appeared eerie, like a black body of water or a cloud on a dark day, quiet but infinitely alive. The dancers’ movements had pauses, but no real stillness, to remarkable effect. When the music, Adès’s “Polaris,” was finally introduced after the dancers took their first leave, in waves, the score only added to this presentation. Re-entering the stage the cast moved in sequence and unison, and explored the different facets of a collective force through various shapes.

The visual effect of so many bodies moving together was certainly impressive, but more so was Pite’s ability to transform the dozens of individuals into a unified whole and gently push to the periphery the viewer’s discernment and recognition of its parts. While in dance it’s generally difficult to cause such a perceptual isolation without the use of props of some kind, Pite accomplished exactly that. The steps Pite employed weren’t particularly complex, with infinitely interconnected moves mainly consisting of body waves and horizontal transition that were earthy, dropping and weaving with the ground as the home base, but their effect was remarkable. The ballet looked like a reflection of the entropic nature of the collective, sublime and mind twisting, but in a quiet, meditative and wholly engaging way, giving the audience, at last, a perfect visual complement to the presented Adès music.

copyright © 2015 by Marianne Adams