Eloquent Passages

“Castles,” “Fabulist,” “Dome”

Doug Varone and Dancers

The Joyce Theater

New York, NY

December 2, 2014

The three works presented by Doug Varone and Dancers at the Joyce Theater each told a different type of story. The 2004 “Castles” opened the night with formations and disintegrations laced with narratives resembling and inspired by fairy tales, the New York premiere of “Fabulist,” a somewhat autobiographical solo performed by the choreographer himself, was a deeply moving storyteller’s monologue, and the world premiere of “Dome” left plots aside and instead spoke the music of Christophe Rouse’s Pulitzer Prize winning “Trombone Concerto.”

Leading off the program, the critically acclaimed “Castles” embodied the rhythms of Sergei Prokofiev’s “Waltz Suite” accompaniment in interactions and steps, as the dancers came together and apart, triggering different tales of conflict and fascination, love and courtship, estrangement and belonging. Varone’s free-flowing choreography charged certain sections with a staccato of jumps and embellished the more lyrical and fluid moments in others. The passionate duet between Hsiao-Jou Tang and Eddie Taketa was particularly captivating, as the dancers crawled on the floor and periodically lifted each other as though fighting death and providing revival. The emotion only kept building when Tang passionately and desperately lay on top of Taketa as their duet’s music faded, calling to mind Romeo and Juliet. The work’s more jovial parts had comedy, particularly in the cheery duet between Hollis Bartlett and Alex Springer, which resembled a courtship, and the grand finale set to the famous waltz from the ball scene in “Cinderella” presented a unique and liberated way to feel the grandness of the famous music with the company’s eight dancers’ free and liberated movements, jumps and reaches.

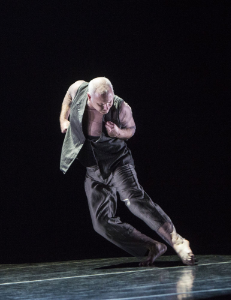

The light energy left by “Castles” was replaced with the more somber and intimate “Fabulist” set to the emotional songs from “Death Speaks” by David Lang. The piece began with the 58-year old Varone, who has been absent from the stage for eight years, standing in a pool of light at the top of a dark stage and moving toward the audience. As he began his narrative, the performance felt deeply personal and seemed permeated with the passion and tenderness of someone who loves his craft, both as a creator and performer, using the dance as a way to express that emotion. Although the music contains lyrics, the work rarely connected to them or their death theme and did not seek to express them, but when such connections were made they were powerful – “I love all of you” sang the uncredited voice toward the end of the performance and Varone dropped to his knees facing the audience, as though directing the sentiment at the viewers.

Much of this mesmerizing and intimate piece seems to tell the story of the creative process and craft of storytelling through dance, but the brilliance of Varone’s work fills it with choreographic double entendres: the same movements could either be interpreted as a story told by the fabulist or a description of what he goes through in crafting the tale. At one point Varone knelt with his hands behind his back like a slave, either telling a story about a captive man, or representing the ideas’ bind. Indeed, Varone’s fabulist seems beholden to threads of stories yearning to be woven together and shared. He would grab at them in the air with his fingers, hold an invisible whole that seemed to materialize in his hands, balance it on his shoulders, then mime writing in the air, and put a silencing finger to his lips. At times the idea would take hold of him, and he would clasp his head, as though stabilizing his mind in his hands. Ben Stanton’s dark lighting design and a very creative use of the spotlight with which Varone interacted throughout the work, added to the tone and presentation.

“Dome” was diametrically opposite to the first two dances. Unlike the other pieces, Varone’s construction did not layer the score with a narrative but rather echoed the music in the dancers’ bodies. The approach allowed the dancers to be extensions of Rouse’s score, the eight of them resembling its certain passages, instruments and different moods and at times remaining immobile, shifting the audience’s focus to the sonic presentation.

Varone does not define the story embedded in the music, but instead gives the score center stage and lets it do the talking. The piece originally had a working title of “Symmetry & Narrative” which was referential to the music’s structure and the emerging narrative within its symmetry. The renaming to “Dome” seems particularly apt however when it becomes evident that the world that takes shape within the score consists of coexisting and alternating chaos and order. The symmetry in the music is not linear, and the notes, and so the dancers, are contained within it as it curves around the more violent high points.

Periodically the dancers’ movements are slowed down, and indeed when they are first presented the slowly lifting curtain reveals them immobile. As the work progresses, the dancers would slide across the floor, then cut their trajectory short. When certain dancers’ music stops or gets interrupted, such as by a blaring trumpet, so do those dancers, allowing the physical representations of the interfering passages to become the focus. During the work’s more explosive points, the slap of percussions in the score are echoed with aggression through grand battements as the dancers move forward; the bursting chaos of random notes in the music comes with isolated but explosive jumps. The choreographic language in “Dome” is perfectly calibrated to the music, not adding any more to the physical expression than what is contained in the score, full of complexity, but not complication. When the curtain slowly falls to end the piece, the dance seems to remain ongoing; a welcome take-away from a work deserving of repeat viewing.

copyright © 2014 by Marianne Adams