Debuts in Black and White

"Apollo", "Monumentum pro Gesualdo", "Movements for Piano and Orchestra", "Duo Concertant", "Agon"

New York City Ballet

David H. Koch Theater

New York, NY

October 1, 2014

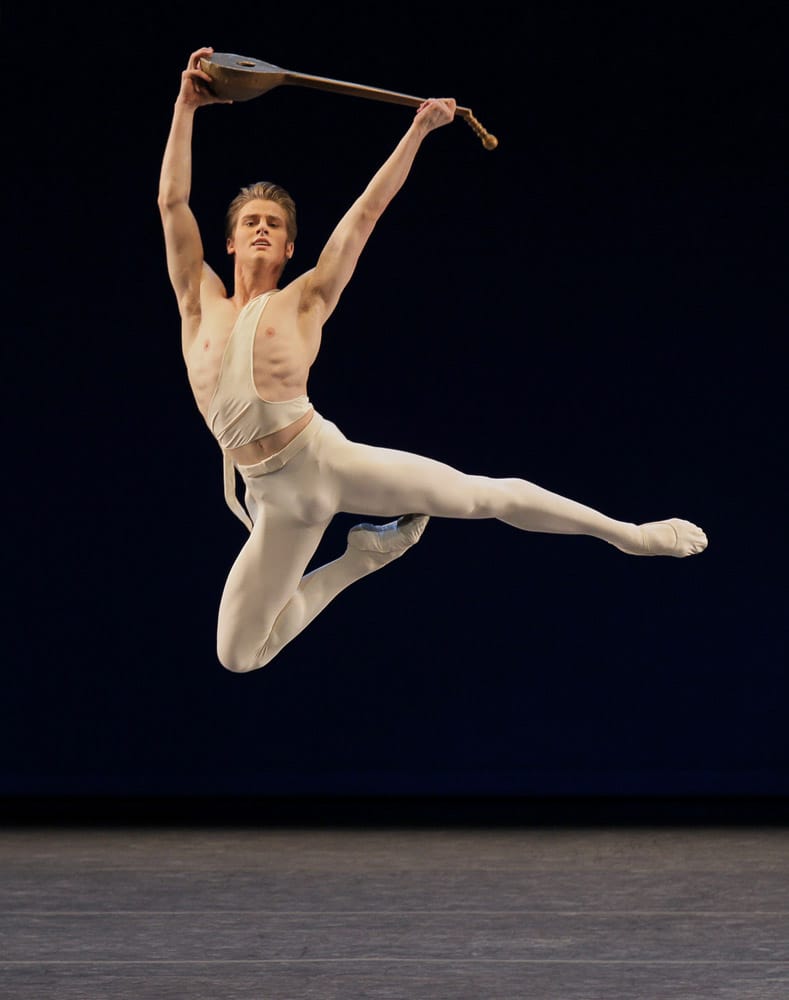

Balanchine in black and white certainly offers a lot of options, and if theme programming is required, this one certainly was bracing. Though there was a certain lack of variety, there were interesting themes running through, as Apollo danced with the same off-center power as the unnamed swain in "Duo Concertant", and "Movements" has the astringent order that shines so brightly in "Agon". Chase Finlay, with his blond innocence and classical body, was an "Apollo" to the manor born, but it took him some time to get there, as he gave each dance its own flavor, testing his strength in the opening, off-balance solo, playing with the muses, and then striding off to Olympus. There were intimations of nobility, of course, from the beginning, but there was a fresh, experimental power to his opening, as he bent and twisted around the lute. The pas de deux was more subdued, as if he was absorbing his fate. The final walk before the ascent (oh, for that staircase) was not as transcendent as some more experienced Apollos, but there was something so moving about his youth.

Maria Kowroski was Terpsichore, a role she is certainly physically destined for. But there was something a bit inert about her performance, all shapes but little substance. There was no feeling of true nobility as she flung those beautiful legs out, but stared a bit blankly at the audience, as if she were reading from an invisible teleprompter. Sara Mearns was an urgent, passionate Polyhymnia and as usual made every gesture resonate; I especially remember her little pause before reaching her arms to join the linked circle, as if she were thinking about what it meant to join the group. Gretchen Smith made her debut as Calliope and danced cleanly and clearly, though as yet she didn't make her character as distinctive as some do.

Amar Ramasar also made his debut as the swain in "Monumentum/Movements". He is often cast in quirky, loose-limbed parts and dances with an appealing openness, so his courtly, calm demeanor in the courtly, calm "Monumentum Pro Gesualdo" struck a welcome note. His intense concentration kept the connection with his partner (the willowy Rebecca Krohn) even when he stood quietly in the back watching her; there was something absolutely magnetic about his presence. He seemed a completely different dancer in "Movements for Piano and Orchestra", crouching, bending, and twisting with a cool, detached nonchalance.

There was nothing nonchalant about Ashley Bouder's debut, with Robert Fairchild, in "Duo Concertant". As yet, she didn't seem quite comfortable in the opening, as the dancers stood quietly at the piano listening to the music, and she seemed to turn her head on cue. Fairchild, on the other hand, dominated the stage by listening and watching with a casual intensity that pulled in the audience and made the opening seem like it was listening to music at a private party.

Once Bouder started to move, however, she looked right at home. This "Duo" was more explosive and playful than most. Her dancing was smooth and sculptured, and it bubbled with energy. Fairchild, too, was dynamic, carving through the shapes, echoing many of Apollo's off-center dynamics. Their performance didn't have the elegiac, wistful undertones of some I have seen; it was immediate, youthful, and full of joy. Bouder is not a dancer of smoke and moonlight and the ending, where she disappears into blackness, did not have quite the air of timeless loss that some dancers can give it, but it looked neither hokey nor melodramatic.

There were more debuts in "Agon"; of the principal dancers, only Sean Suozzi in the Sarabande had danced it before, but it was a confident and polished performance. Teresa Reichlen and Adrian Danchig-Waring danced the pas de deux. Some of the original oddness has disappeared, as the woman has taken more control over her steps, and tends to push herself into positions rather than being manipulated, but Reichlin danced with a cool, crisp impartiality, so much more interesting than the pipe-clearners in heat that we sometimes see. Danchig-Waring was a supportive, unobtrusive partner.

Suozzi's Sarabande combined an elegant carriage with quirky, off-center moves, clearly showing the formal basis of the dance without making it a caricature. Savannah Lowery was less interesting in the Bransle Gay, and her slightly smudged footwork hid the dance's classical roots. She had no trouble with the tricky balances in the Bransle Double, but I miss the witty little nod that years ago the dancer used to give the audience as she walked off the stage, that brief, bright chink in the fourth wall.

copyright © 2014 by Mary Cargill