Dances, Squared

“Square Dance”, “Episodes”, “Western Symphony”

New York City Ballet

David H. Koch Theater

Lincoln Center

New York, New York

September 20, 2025, matinee

New York City Ballet’s second all-Balanchine program of the Fall season showed two variations on bouncy American square dances (the serenely classical “Square Dance” from 1957 and the raucous “Western Symphony” from 1954), sandwiching the austere, angular “Episodes” (1959) to selections of Anton Webern—something for everyone. I do miss the old weekly smorgasbord programming approach, but the current style of one or two programs a week certainly has its benefits; the dancers looked much more prepared (no dress-rehearsal first night vibes) and, especially in “Western Symphony” they seemed to be dancing for pure joy. There were a number of debuts, and all were danced with a confident authority and a distinctive individuality. And a special welcome to the new soloist, Ryan Tomash, who ripped through the last movement of “Western Symphony” like he had been born in the saddle. (He was actually born and trained in Canada, which does have lots of wide open spaces, and has been dancing with the Royal Danish Ballet since 2017, which has lots of style, a wonderful combination.)

Emma von Enck showed a lot of style in her “Square Dance” debut. She has always been a crisp and clear allegro dancer but her performance as the glyph in “Scotch Symphony” showed that she has a soft, lyrical side. Her dancing in “Square Dance” showed both sides; her allegro was precise and thrilling and her phrasing delicate, as she seemed to be tossing her gargouillades around like confetti, while her upper body was soft and fluid. Her performance, though, was not just a technical triumph, she brought a friendly warmth and wit to her dancing, acknowledging her partner, Taylor Stanley. Their slightly distant, introductory courtly bows were both intimate and elegant. The mirroring arabesque sequence, so precisely shaped, seemed to be an echo of their thoughts, and their pas de deux was danced with a hushed reverence; the landings were so quiet it seemed as if they were dancing on clouds.

Stanley first danced the role in 2011 while still in the corps. Even then, he gave the supple, introspective, mysterious solo, added to the ballet in 1976, a haunting power. This afternoon, he seemed to be living in a world of his own, bending backwards with a resigned surrender, reaching for an invisible partner with a contemplative melancholy, moving with a smooth, weighted elegance.

There is little smooth about “Episodes”, a spiky exploration of Webern’s atonal music. India Bradley made her debut in the opening episode, moving with a restrained and impassive two-dimensional calm. She controlled her long arms and legs, making shapes rather than slamming extensions. Emily Kikta and Preston Chamblee danced the second movement, teetering on an invisible tightrope and moving in an out of the spotlights with a witty insouciance.

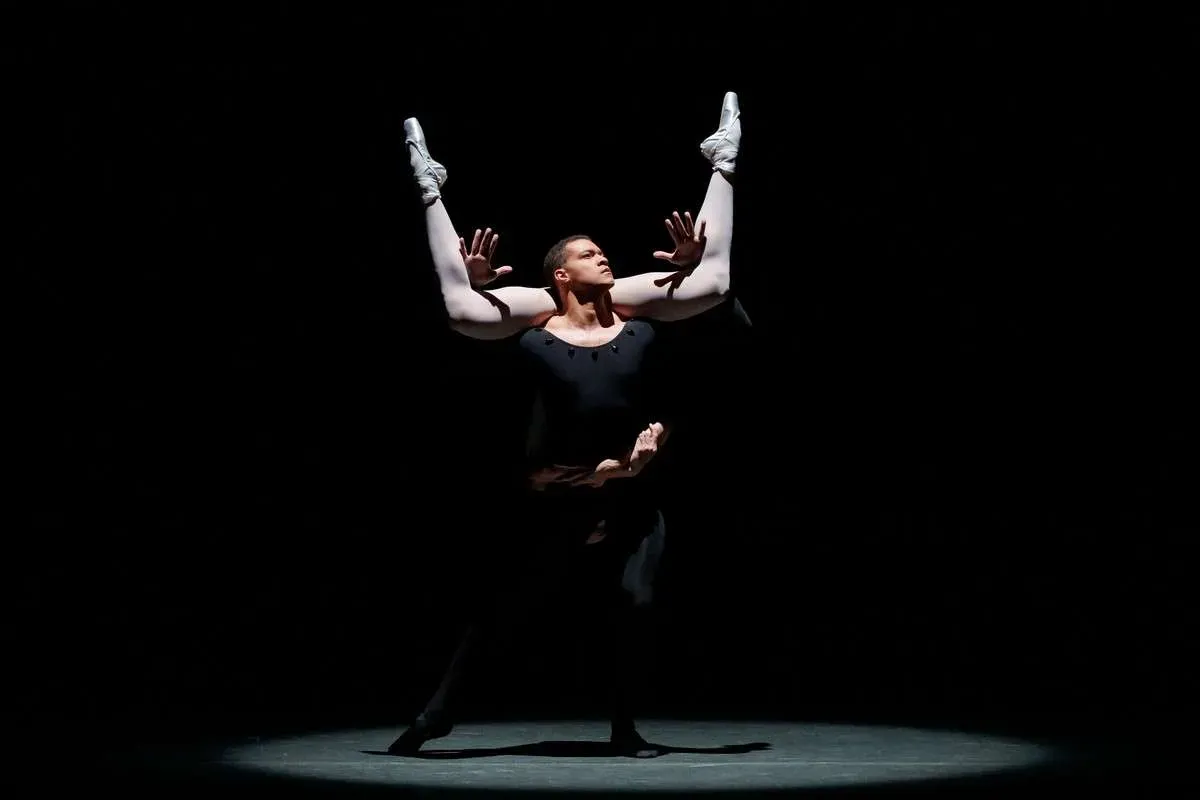

Dominika Afanasenkov debuted in the spiky third movement, partnered by Christopher Grant. Though he spent most of the section manipulating her into odd and intricate shapes, Afanasenkov was not a passive doll and she seemed to be in control, as if her legs had a mind of their own. Sara Mearns, in the majestic final section set to Bach by way of Webern, certainly has a mind of her own, and, though she has been more intense in the past, she made the final lowering of her arms into a powerful blessing.

“Western Symphony” had a completely new cast of principals, and they all looked like they were having a wonderful time. Balanchine’s slightly over the top valentine to the imaginary American West is also a precisely structured classical ballet, whose original four movements were modeled on the traditional symphonic structure ((Balanchine removed the third movement, the scherzo, in 1960; it did make a brief reappearance in the 1993 Balanchine retrospective, but has since disappeared) and whose choreography, underneath the swagger, is full of classical steps and formal shapes. The exuberant dancers, the men in hats and the women in headdresses, could, with a few tweaks to the choreography, join in all those Hungarian, Polish, or Spanish dancers which spiced up the nineteenth-century ballets.

Alexa Maxwell and Alec Knight opened the hoe down, combining an aw shucks casualness with a sassy swagger, while making the tricky partnering look easy. The second movement, an adagio interlaced with the plaintive strains of “Red River Valley” (the music is American folk songs orchestrated by Hersey Kay) tells the story of Odette of the prairie; it is very easy to overplay, but both Olivia MacKinnon and Victor Abreu played it almost straight, and went for wit as well as laughs. MacKinnon bourréed on with a slightly confused expression, as if she had expected to find a lake, but was determined to carry on regardless, and Her Abreu, was very funny as a practical Siegfried who decided if he couldn’t be with the one he loved, the four little dance hall girls would do quite well.

Tomash and Isabella LaFreniere were an explosive couple, leading the rousing finale. LaFreniere seemed to revel in the luscious hip swivels and looked amazing in her hat. Tomash, who seemed especially enamored with his red scarf, danced with a warm bravura, tearing through the jumps and pounding the stage with enthusiasm; those dances, square and otherwise, sent the audience home happy.

copyright © 2025 by Mary Cargill