Coloring in the Black and White

“Concerto Barocco,” “Monumentum pro Gesuaido,” “Movements for Piano and Orchestra,” “Episodes,” “Four Temperaments”

New York City Ballet

David H. Koch Theater

New York, NY

October 18, 2015 (matinee)

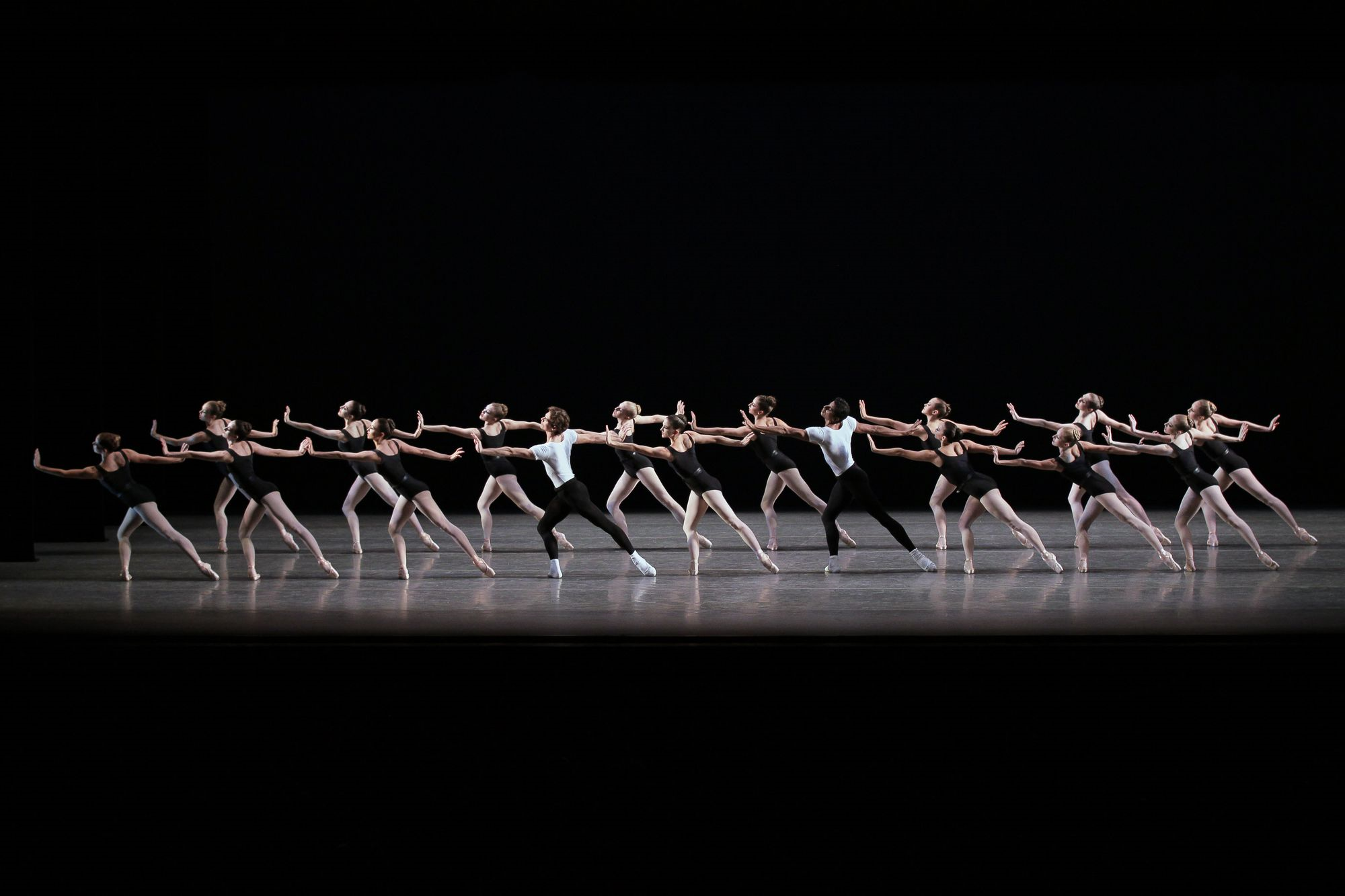

For all the dedication to new and inventive ballets that NYCB stands for, sometimes nothing works as well to please the audience as a collection of Balanchine classics that strip away pomp, circumstance, or the quest to arouse shock or awe, and simply present excellent ballet in all its purity. The five costume-less works of the company’s “Balanchine Black and White” program did exactly that, with added color in the details of the dancers’ individuality, and the company’s evolving identity.

The leading roles in the program’s opening ballet, “Concerto Barocco,” were danced by Sara Mearns, Teresa Reichlen and Russell Janzen, but its actual stars were the eight ladies of the corps. While the principals presented clean but listless dancing of divergent styles, reflected most acutely in the differently styled port de bras of the two women, the corps’ steps were as tight and melodic as the Bach music’s string section. From the purity of their leg movements to lingering arms that protracted the varying notes’ sounds, the eight women really were the corps – the body – of this work. The principals did try to keep up and produce individual interpretations of this ballet classic, but ultimately underwhelmed thanks to the unshapely hip lines and awkwardly unfixed poses from Reichlen, particularly during the usually mesmerizing streams of lifts that Janzen tried to salvage with his assertive partnering, and tired looking performance of the obviously overworked this season Mearns.

There was no such spotlight-stealing by the corps in the next two works, as in their two back-to-back ballets, “Monu- mentum pro Gesuaido” and “Movements for Piano and Orchestra,” Rebecca Krohn and Ask la Cour danced the leading roles with powerful individuality and in a way that made the two ballets contrast, rather than bleed together, which may well have been the risk of such programming. In “Monumentum” Krohn gave her pliant execution of the steps a tender, reflective quality that amplified the lyrical score, with light arabesques that looked suspended in midair, all opposite an assertive, but not overtly commanding la Cour. The roles flipped in “Movements,” with Krohn possessing the stronger character and la Cour appearing more subdued and complementing to her style. Their steps flowed between accented poses and smooth transitions, particularly in the sequence where holding hands together the couple weaves in and out of varying forms in center stage, and every movement seemed purposeful as they danced the pauses of Igor Stravinsky’s structural score, but added melody to the connections between the notes’ isolated rhythms.

Following an intermission, “Episodes” brought with it some awaited debuts, though not all of them resonated. In Symphony, Lauren King and David Alberda delivered all the steps, but gave them about as much differentiating flair or individuality as their uniform black and white leotard and tights. They stood out from the three couples of the corps so little that it likely took some time for members of the audience unfamiliar with the work to figure out that they were indeed the leads. Except for a couple of moments where King tried to command the stage in developpés to the side, the duet was largely a missed opportunity. In contrast, another debuting couple, Ashly Isaacs and Taylor Stanley, left the opposite impression with their treatment of Concerto, enhancing the pure and exploratory nature of the choreography with committed delivery of their signature styles and a movement narrative, such that the section transformed into the ballet’s ornate centerpiece. Of course, this was almost to be expect from these two rising stars.

Of the veteran performers, Claire Kretzschmar and Jared Angle were otherworldly in the Five Pieces section, veiling it with suspense and dark energy, while in Ricercata Mearns continued to labor through the steps to the ballet’s and her season’s finish line opposite Adrian Danchig-Waring, who danced with inspiration and sufficient immunity to whatever was afflicting his partner’s performance.

The last work on the program, “Four Tempe-raments,” also offered some debuts, leading off with Megan Johnson’s first appearance in the opening duet. It was a solid, though otherwise uneventful, performance, and contrasted unfavorably with the remarkable delivery of the third duet. There, Ashley Laracey and Justin Peck, not new to the section, danced with a beautiful romantic quality that made the part where Peck wrapped his arms around Laracey in her lean against him feel like the white adagio from “Swan Lake,” though in a purer, unvarnished by costumes or scenery, and somehow more flavorful way.

Two more personality-infused debuts followed, with Tiler Peck’s take on the Sanguinic role appearing predictably energetic and fueled by the spice of her dazzling technique. At times though Peck’s accenting appeared overwrought, and as a result many of the poses of arm and leg counter-position and body tilts looked too extended. Still she made the role uniquely her own, and there’s reason to believe that it would grow more nuanced as Peck grows into it. In the last section, Megan LeCrone as Choleric looked powerful and detached, but only rarely made the choreography’s erratic movement look like irritation. And so, her dancing looked interestingly different but with plenty of room for further development. As with the rest of the program, it wasn’t black and white.

copyright © 2015 by Marianne Adams