Anniversary Presents

"Scènes de Ballet", "The Two Pigeons"

A Tribute to Ashton

Sarasota Ballet

Van Wezel Performing Arts Hall

Sarasota, Floria

March 10, 2017, March 11, matinee, 2017, and March 11, evening 2017

Iain Webb has directed the Sarasota Ballet for ten years, and helped celebrate this milestone by presenting an all-Frederick Ashton program. Though tin is the official tenth year wedding gift, Webb's programing was pure gold, giving the audience the Sarasota Ballet's premiere of Ashton's 1948 "Scènes de Ballet" and a revival of "The Two Pigeons", a work Webb presented in his first year. Both of these works require strong male dancers and Ricardo Graziano's injury left a gap which was filled by a guest artist, Marcelo Gomes from the American Ballet Theatre, who danced two performances of "The Two Pigeons". Guests can be problematic, as ABT's summer frequent flyer policy, now thankfully in abeyance, has shown, but Gomes' integrity and generosity let him fit seamlessly into the company. On opening night, after being almost coerced into taking a solo bow, he turned his back to the audience and acknowledged the company, one artist saluting others.

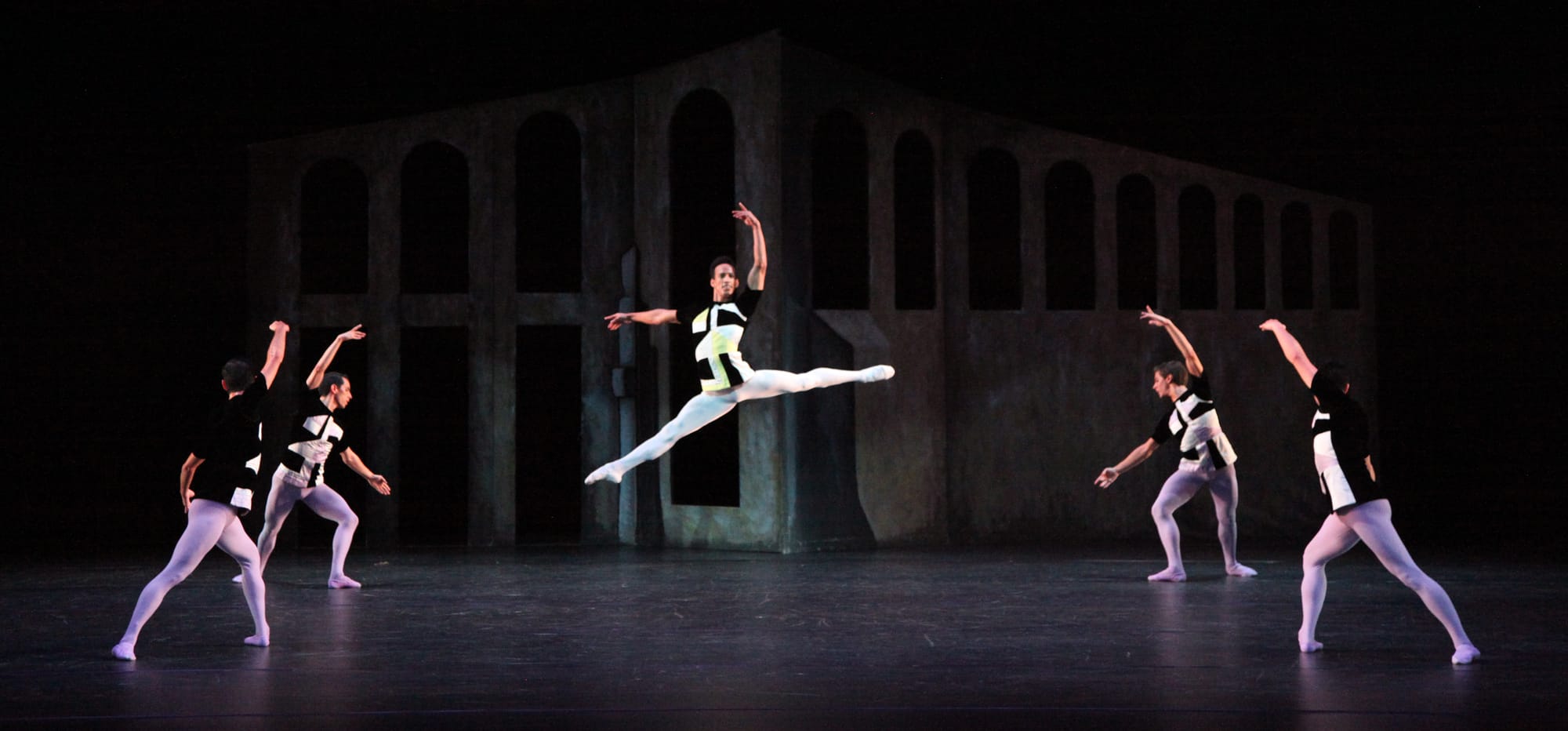

The evening opened with "Scènes de Ballet", an austere, radiant, and endlessly fascinating work set to the 1944 Stravinsky score, written, oddly enough, for the Billy Rose musical "The Seven Lively Arts". This was the ballet, Ashton has said, he would save if he were only allowed one. "The Sleeping Beauty", though, is probably the ballet he would save above all others, and there are many allusions to that work in "Scènes de Ballet". It is as if Aurora had gone to sleep in 1900 and woken up in 1948 to dance in a ballet by a long-lived Petipa who had absorbed all the changing styles. It has the grandeur of the Imperial Court intertwined with the dynamic harmonies and sharp angles of Art Deco joined with New Look chic.

Like Aurora, the ballerina (Danielle Brown on Friday and Saturday evenings and Ellen Overstreet on Saturday afternoon) demonstrates but does not flaunt her technique, and in a clear allusion to the Rose Adagio she gets four partners (plus her prince). These four men (Nicolas Moreno, Kyle Hiyoshi, Thomas Giugovaz, and Alex Harrison with Brown and Edward Banner, Ben Kay, Daniel Pratt, and Wilson Livingston with Overstreet), though, have graduated from the unobtrusive princes of "The Sleeping Beauty" to a dynamic presence, dancing around and through the asymmetrical groupings (Euclidian geometry was one of Ashton's sources). The Sarasota men danced with a bounding musicality and impressive uniformity, handling the technical as well as the artistic challenges with serene confidence. A series of supported pirouettes, as each man seamlessly transfers the ballerina to the next one in mid-turn is a brief, astoundingly difficult nod to the Rose Adagio.

The ballerina gets two solos, the first a glittering tour de force of intricate footwork and the second a sensuous display of the upper body; I once heard Antoinette Sibley describe them as a diamond followed by a black pearl. Brown, with her cheerful and open style didn't quite capture the remote, impersonal mystery the role can have, though her dancing was clear and elegant. She looked more comfortable on the second night, shading her dancing more delicately. Her long, controlled limbs and beautiful proportions showed off the clipped lyricism of the choreography. Overstreet didn't have all the sharpness the role calls for, tending to place her arms in those geometric shapes rather than snap them into position right on the music, but her dancing too was clear and transparent.

Brown's partner, Ricardo Rhodes, flew through the choreo- graphy; he did a series of double tours with a completely calm upper body and a series of unusual jumps, changing feet in mid-air, with an effortless dignity, right on the music. He was affable and engaging, but didn't have all the weight and gravitas this distillation of Petipa's noble hero can have. Edward Gonzalez, with Overstreet, did have weight and presence; he was especially effective in his opening pose, slowly and majestically moving his arms. He has an especially juicy quality to his movement, though his technique is not as scintillating as Rhodes'; the difficult jumps, which Rhodes seemed to toss off, were a bit sketchy.

But "Scènes de Ballet" is more than a collection of technical feats and the twelve corps dancers are its musical heart, with their elegant black berets, pearls chokers, and black wristbands moving sometimes in harmony, sometimes in counterpoint, catching all the little grace notes Ashton heard in the music; their perfectly timed little nods seemed like bubbles from a very dry champagne. The work and dedication that the company showed in making the choreography look easy and natural is truly inspiring and it is too bad that this great work (Sarasota is the first American company to get permission to dance it) got only three performances.

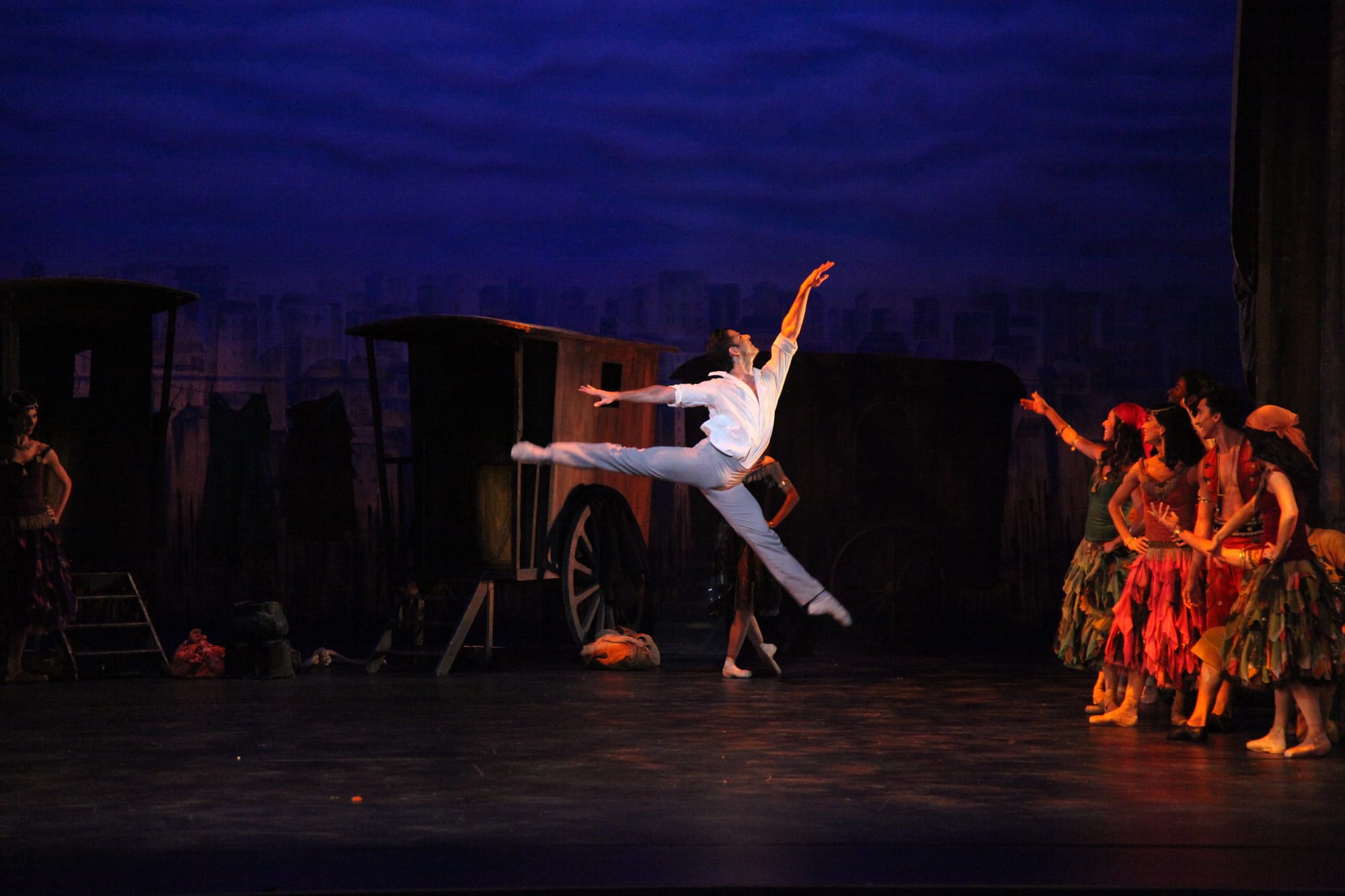

Sarasota Ballet danced "The Two Pigeons" in Webb's first season (2007) and its youthful sweetness suits the company well. A young artist and his model/girlfriend live in a picturesque Parisian garret, though he is tiring of domestic bliss, and a visiting band of gypsies entice him away, only to rob and beat him. He crawls back to his garret (carrying a live pigeon, a symbol of his love) to find his waiting girlfriend who forgives him; basically the Prodigal Son visits La Bohème. Though the situations are not realistic (running off to dance with the gypsies is not a lifestyle option for many people) the emotions are genuine and Ashton translates them into movements so poetically.

Youthful innocence is one of the most difficult moods to make interesting and compelling but Ashton, like Bournonville, creates young love without being coy or cute. The young girl, with her delicate pigeon-like moves, is by turns playful, exasperating as she keeps interrupting the artist, and forlorn when she realizes she is losing her lover, but at all times believable and sympathetic. Victoria Hulland (with Gomes) was completely convincing as the girl, never acting young but letting the feelings come from the steps. Ryoko Sadoshima, in the Saturday matinee, overdosed a bit on the cute, with too many wide-eyed glances at the audience. Her dancing was soft and gentle and she could have trusted that she could move the audience without an extra push. Her sad little solo, though, had real pathos and the final, rapturous pas de deux was danced with and for her partner with a fine and effective restraint.

The gypsy rivals were danced by Kate Honea (Friday and Saturday evenings) and Kristine Kleine (Saturday matinee). Honea was the more enticing and Kleine the more commanding (she looks like she was born to dance the Prodigal's Siren) and both whirled through Ashton's fast footwork. The poor artist didn't stand a chance.

Ricardo Rhodes was the Saturday matinee's painter. Sadoshima's coy, rather artificial approach in the first act made it hard for Rhodes to develop a believable character since much of Act 1 is a dialog between the two. But he clearly enjoyed his romp with the gypsies and his Prodigal Son moment, when tossed out of the camp with his hands bound, was danced with a powerful understatement. Ashton does not require extraneous acting to show emotions, and some dramatic tugging and straining at the rope would destroy the picture that the choreography, with its constantly shifting upper body, creates of ties that limit us and ties that bind us to one another.

Gomes, with his ability to submerge himself into a character, was detailed, sympathetic, and completely winning as the exasperated painter, seduced by the idea of freedom. Though he can be a one-dimensional hero with the best of them, his imagination and intelligence make his weaker, flawed characters so vivid and his young painter is as moving as his Albrecht or his Solor. Both he and Hulland here especially memorable in showing the emotional arc and growth of their characters, young and often thoughtless in Act 1 and grief-stricken, forgiving, and loving in Act 2. Ashton can create such rich feelings out of simple things –who else would make finding a pigeon and placing it in a young girl's hands a tear-jerking moment? (The second pigeon, unfortunately, was not quite ready for her close-up, and couldn't manage the flight into the room at the musical climax.)

Gomes was not the only guest artist that weekend. Barry Wordsworth, the Principal Guest Conductor of the Royal Ballet, let all three performance. Live music, so often seen as a luxury, is thriving in Sarasota. Stravinsky's "Scènes de Ballet" was welcomed by Billy Rose, who complimented Stravinsky on his "great success", but promised a "sensational success" if Stravinsky would allow Rose to have it reorchestrated. "Satisfied with great success" was Stravinsky's laconic reply. Sarasota Ballet, too, should be satisfied with great success.

Copyright © 2017 by Mary Cargill