A Long Winter's Night

"The Winter's Tale"

National Ballet of Canada

David H. Koch Theater

New York, NY

July 29, 2016

Shakespeare's "The Winter's Tale" is a play about jealousy, madness, grief, regret, and redemption, combined with a complicated plot and questionable geography (the sea cost of Bohemia plays an important role). The National Ballet of Canada, as part of the Lincoln Center Festival, appeared in Christopher Wheeldon's 2014 co-production with the Royal Ballet and Canadians; the choreographer tells the story with imagination and verve. The sets (by Bob Crowley) and the special effects (by Basil Twist) are stunning, while the music (by Joby Talbot) is effective as a cinematic score, reinforcing the moods and story without revealing any depths, though the very long folkish music of Act II ambles along with few hints of rhythm or melody. Talbot is no Minkus.

Nor is Wheeldon Petipa; his choreography was expressionistic rather than classical, with a lot of gestures and very little pattern. The ballet is loaded with bourrées, frequently backwards, to signify anguish, and arabesques, to signify rapture. The bones of the story are clear; I especially liked the Prologue which concisely showed two Princely pals (Leontes and Polixenes, the future kings of Sicilia and Bohemia) growing from boys to men. But the emotions depended more on the dancers' gestures and expressions rather than the shape of the choreography. The most dramatically and emotionally effective moment had no dancing at all; it came at the end of Act I, where, based on Shakespeare's famous stage direction – "exit, pursued by a bear" – the secondary character Antigonus was chased by an oversized projection on a billowing silk curtain. It was an impressive and imaginative piece of stagecraft, which added little to the story.

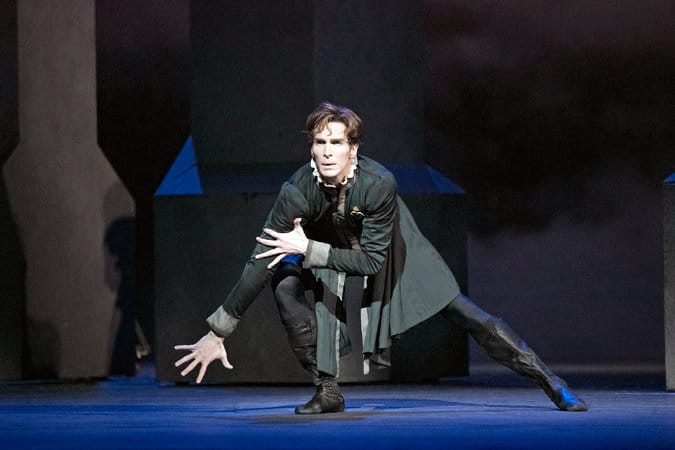

Fortunately, the Canadian dancers were subtle and imaginative actors and most were able to triumph over the somewhat repetitive and limited vocabulary. Evan McKie was Leontes, the King of Sicilia whose irrational and obsessive jealousy led to his son's and his wife's deaths and the abandonment of the baby daughter Perdita on the shores of Bohemia (where Antigonus met his dramatic end). He avoided the easy Dr. Hyde interpretation, and gave his descent into madness a dignified, reluctant inevitability. His quiet joy when he recognized Perdita was exceptionally moving, as was his deep, humbled bow to his wife as she came back to life.

Jurgita Dronina was Hermione, his innocent wife. Unfortunately she had to spend most of the first act being manhandled while sporting a large baby bump (an unnecessary and almost grotesque grasp at realism, so at odds with ballet's abstract nature), but even that couldn't destroy her innate nobility. Paulina, her companion and the story's moral compass, was the former Bolshoi dancer Svetlana Lunkina, who gave a luminous and soulful performance, even with all her flexed feet and invisible accordion playing gestures.

Elena Lobsanova was a sweet-faced Perdita though she could find little depth in the repetitive and unimaginative Act II choreography. She apparently was told to keep smiling and her expression never changed even when her poor shepherd of a foster father gave her a large emerald (found with her when the baby was abandoned on the coast); surely she would have wondered where it came from. She smiled at her Princely lover Florizel, son of Polixenes (danced with bounding abandon by Francesco Gabriele Frola), and kept smiling when he disguised himself as a peasant. Prince or pauper, she flung herself at him with her legs wide open and their various athletic pas de deux, full of impressive ice dancing lifts, had no emotional arc. I had the feeling that Polixenes may have objected to their marriage (in another episode of Kings Behaving Badly, he pulls a knife on the poor shepherd) not because she was a peasant but because of her low IQ.

Act II, set in Bohemia, is basically one long folk dance, as the frisky corps, in vaguely Macedonian outfits (the men all wear skirts), danced to the faux-folk music; the dance, full of flexed feet and swaggering torsos, was about as authentic as Shakespeare's geography. Wheeldon's lack of structure was especially evident here, as the corps circled colorfully but endlessly around the stage without pattern or purpose (did Wheeldon learn nothing from Balanchine's "Cortège Hongrois"?); I for one was wishing the bear would make another appearance long before it was over.

Despite the padding, the company looked very good, with beautifully formed feet, a natural carriage, and a crisp, unexaggerated style, combined with a fine dramatic presence. They made the ballet look both interesting and significant.

copyright © 2016 by Mary Cargill