A Fable for Our Time

"The Golden Cockerel"

American Ballet Theatre

Metropolitan Opera House

Lincoln Center

New York, New York

June 1, 2017

Alexei Ratmansky's version of "The Golden Cockerel", based in part on the earlier Fokine ballet, is a hybrid work, a partially mimed (and quite complicated) story with episodes of dancing set to the music of Rimsky-Korsakov's opera. The original 1914 full-length ballet was danced to the opera with singers on the side of the stage, though Fokine's 1937 one-act revision did away with the singing. Ratmansky choreographed a full-length ballet, with the arias rearranged (or sometimes, as in the famous "Hymn to the Sun", smoothed out) for instruments by Yannis Samprovalakis. The score is still magical, and it has the stunning, Russian folk style designs by Natalia Goncharova, reinterpreted with occasional lapses into glitter by Richard Hudson, and a sour, bitter story of cowardice, greed, and foolishness.

Ratmansky choreographed it in 2012 for the Royal Danish Ballet, a company with a vibrant mime tradition, and several of the main characters (fat, greedy Tsar Dodon, the bombastic General Polkan, and the mysterious Astrologer) are mimed roles; so too is the small role of the feckless but kind-hearted Housekeeper (Martine van Hamel, who was both funny and pathetic). ABT currently has some impressive mimes of its own and Alexei Agoudine was a fine, if despicable, Tsar, so lazy he would rather abdicate than protect his kingdom and so lascivious he could turn from his dead sons to chase a pretty face. Roman Zhurbin was a pompous, vainglorious General, convinced that fighting would solve everything, especially if someone else went to battle.

James Whiteside was the enigmatic Astrologer, one of those black-robed, sinister old men who control what may or may not be real, like his cousin the Charlatan in "Petrouchka". Whiteside's hands were especially vivid, as he created the Golden Cockerel out of this air, though the Astrologer's menace is undercut by his chintzy costume – there is nothing mysterious or frightening about black sparkling lurex.

The seductive Queen of Shemakhan (Stella Abrera) and the mechanical cockerel (Skyler Brandt) were the only roles using point work. Abrera was also partly undermined by her costume, as a dime store version of a 1914 Paul Poiret does not evoke Central Asia and is a long way after Goncharova's sensuous design. (Long braids are a lot more enticing than flopping feathers.) Abrera, as the Queen who seduces the deluded Tsar to win his kingdom, used her sensuous arms and her expressive face well, though the role is choreographed for laughs and is danced like a kitten rather than a cold-hearted conquerer.

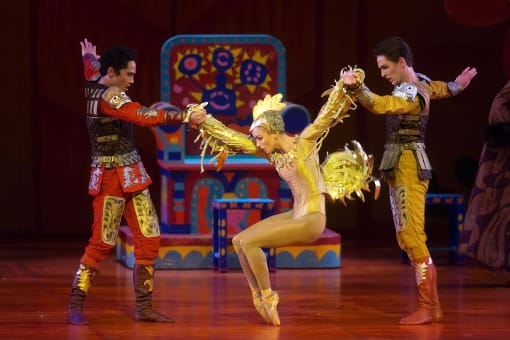

Brandt was scintillating as the mechanical bird who would crow when the kingdom was attacked. Her dancing was full of sharp, brilliant twists and turns and her face was both vivid and impassive; somehow the light seemed to reflect off her eyes, which looked large, flat, and metallic, perfectly capable of pecking the duplicitous old Tsar to death.

Jeffrey Cirio and Joseph Gorak were the Tsar's useless offspring, whose pristine classical dancing was an ironic contrast to their laziness, cowardice, and stupidity -- they manage to impale each other on the battlefield.

The ballet, with its detailed mime scenes (which tend to get lost at the cavernous Met) and complicated story (how does a choreographer show that a mechanical bird will crow when enemies attack?) will probably never be a popular hit with an audience who hopes colorful sets and shimmering music offer a chance to relax into a pretty fairy tale. Rimsky-Korsakov wrote his opera in part as a protest against the Tsar's policies leading to Russia's disasterous defeat in the 1905 Russo-Japanese war, but the cynical story of a lazy, lustful king with stupid, greedy offspring, advised by bombastic war-mongers is certainly not limited to Russia of 1905.

Copyright © 2017 by Mary Cargill