Together to the End

“To Create a World”

Gallim

Joyce Theater

New York, NY

February 13, 2019

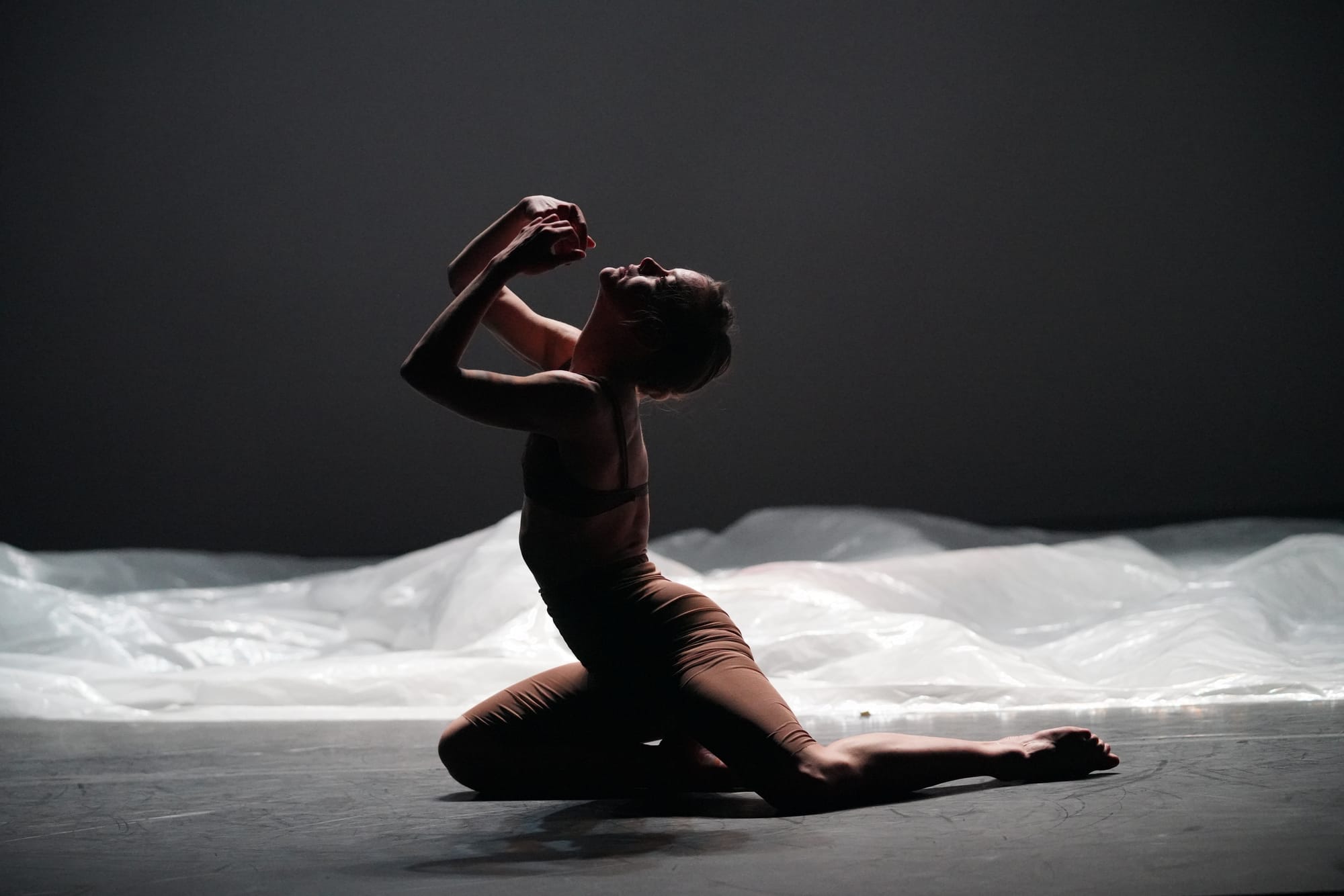

It takes some chutzpah “To Create a World.” Choreo- grapher Andrea Miller, along with the Gallim dancers, had good reason to attempt the feat, in the premiere of their new work. On a stage of swirling, contorted bodies bathed in deep color and harsh swipes of light and dark, Gallim inhabited a place apart, in a community of unique movement and connection.

The Brooklyn-based choreographer has always traded in idiosyncratic movement, pushing bodies into curves and angles that are often more architectural and sculptural than fluid. The world Gallim created in this new piece used their unique physical patterns to build a world of purgatory, struggle, and regimentation as well as deep human connection. The light and dark of emotion shared the stage, while the dramatic stage lighting by Burke Brown – deep shadows, harsh spotlights, brilliant baths of color – offered another metaphoric angle on the struggles in this world. The bespoke music by Will Epstein, played on a diverse group of instruments by his group of three, slid from tinkling and melodic to percussive and techno, each soundscape offering a different medium for new scenes or characters.

The dancers’ contributions to the choreography were evident in the individuality of their movement. Particularly with Gary Reagan’s often tortuous solos, it was hard to imagine anyone else moving quite the way his skeletal powerful body does, his strength and flexibility offering unique patterns of a back bent to what seemed to be breaking, or legs that shot out from his hips as if wrenched from the socket. He tied himself up with his own body; when he rose on the strength of two large toes, his backbend was swanlike and contorted in equal measure.

The other dancers moved in their own distinct ways as well. Even when movement was parallel – often a pair of dancers moving together in shadow, while a soloist writhed in a spotlight across the stage – the two dancers echoed each other but didn’t try to match identically. In scenes where five dancers snuggled back to front in an angled short-stepped march, they became a single entity, like a caterpillar or slithering amphibian – but with five distinct heads. Along with the shifts in music, the pairings and groupings suggested other-worldly beings.

The dance was structured with several symmetries. As the audience members were being seated, a large panel of white fabric stretched across the stage, and periodically bubbled from underneath, the limbs of an anonymous body pushing shapes out of the fabric – maybe a knee or an elbow, maybe the crown of a head. Later in the piece, that same fabric, stretched across the back of the stage, curled around Reagan’s body, swallowing him like vertical quicksand – if we had been seated behind the stage, we would have seen some version of the bubbling screen that had greeted us at the start.

As that stretched fabric – the “curtain” – rose, it released half of a near-naked body underneath the fabric panel onto the stage apron; that dancer joined several others, also barely covered bodies in dark shadow throbbing on the stage in gyrations. Each dancer torqued, rolled, and jumped, mostly alone but breaking into occasional pairs; they disappeared into darkness.

From the blackness after the opening scene, a couple emerged – Reagan and Allysen Hooks, less partners than a pair of citizens in this strange new world, moving in their own powerful ways and separated by most of the stage. When they came together, it was less as lovers than as fellow travelers, despite the intimacy of many of their interconnections. They closed the work, too, their lips finally meeting, only to dissolve into a continuing struggle.

Although it felt like more, the entire cast was comprised of seven dancers -- six company members, plus a Gallim apprentice, the excellent Ashley Hill. Each had a distinct personality – Sung was feral as she attacked the movement, then was dragged around the stage by her limbs. She brought a fierce energy to her duets, as the virtuosity of the – often disturbing – individual movement also fed beautiful paired movement with the other women, like the one that paired her with Hook, as they cradled each other like snuggling children.

The male duet, David Maurice and Dan Walczak, were like magnets who were entangled in their attraction, then repelled to opposite poles, wrenching themselves, at one point, into a pair of crabs, stacked upside down. When Hooks became enfolded in a huge white plastic sheet, her hidden partner, Reagan, dragged her into the folds like a spider entrapping a fly in his web. At the same time, though, there were moments of breathtaking trust – one dancer fell backward, full weight, trusting that her head would be caught in waiting arms instead of crashing to the floor.

In this grotesque and magical world (a bit of Hieronymous Bosch in motion,) each player had their own spaces, their movement contribution. Each was both figure and ground, paired and solo, and always part of a community. They were a hive as they drilled into the beat at the work’s close – twisting, rolling their hips, and prancing. Gallim created its own reality in this hour-long world; it was not safe, comfortable, or beautiful, but it was powerful, and every member belonged nowhere but within it.

copyright © 2019 by Martha Sherman