To Grow A Garden

"The Sleeping Beauty"

New York City Ballet

David H. Koch Theater

New York, NY

February 13, 2026

Peter Martins’ 1991 production of “The Sleeping Beauty” returned to City Ballet for two well-sold weeks; it has remained basically unchanged for 25 years, with the same strengths and weaknesses. Fortunately this performance, with Indiana Woodward and Chun Wai Chan as the royal couple and Ashley Laracey as the Lilac Fairy, and a number of debuts in supporting roles, was definitely on the strong side. Yes, the production is still unbalanced, with the traditional Prologue, and Acts I and II performed together, making a very long wait for an intermission (especially for the many children in the theater), and breaking in the middle of the voyage rather than before the 100 years sleep disrupts the flow of the story and the music. There are still unfortunate deletions (I do miss Carabosse’s mockery of the fairies and the King pardoning the knitting ladies) and now that many dance goers have seen versions based on the old notations, with the spiteful, petty, and vindictive Carabosse being forgiven and invited to the wedding (though closely guarded), Martins’ fire breathing harridan disappearing in a puff of smoke looks like a one-note cartoon. But Martins did keep much of the traditional choreography, especially for Aurora’s three set pieces (the rose adagio, the vision scene, and the wedding pas de deux), and enough of Petipa’s great work and Tchaikovsky’s magnificent score remain to elevate the evening.

Aurora is a challenge, not just because of the technique needed (jumping in cold to the rose adagio is bad enough, but having to look happy is another issue), but she must change character in each act. Aurora is a bouncy, adorable 16 year old in Act I, a disembodied vision in Act II, and regal wife in Act III. Usually dancers are more comfortable in one of the guises, but Woodward was completely convincing in each act.

Her Act I dancing had a gentle radiance, eager and shy as she greeted the princes. Though the fourth prince in the first go round of the rose adagio was a bit short changed, her rotating attitude balances were steady and secure; I loved the slow descent of her leg as she rolled off point. Her solo was calm and luminous, as she showed off her beautiful arabesque and secure footwork, and her excitement seemed to build as each jump in the final diagonal grew higher. It was a beautifully calibrated performance which seemed to emerge from the music, a vivid and natural portrait of a young, happy, and delightful girl. The confused spasm of pain from the spindle, clearly the first time anyone had hurt her, was almost shocking in its intensity.

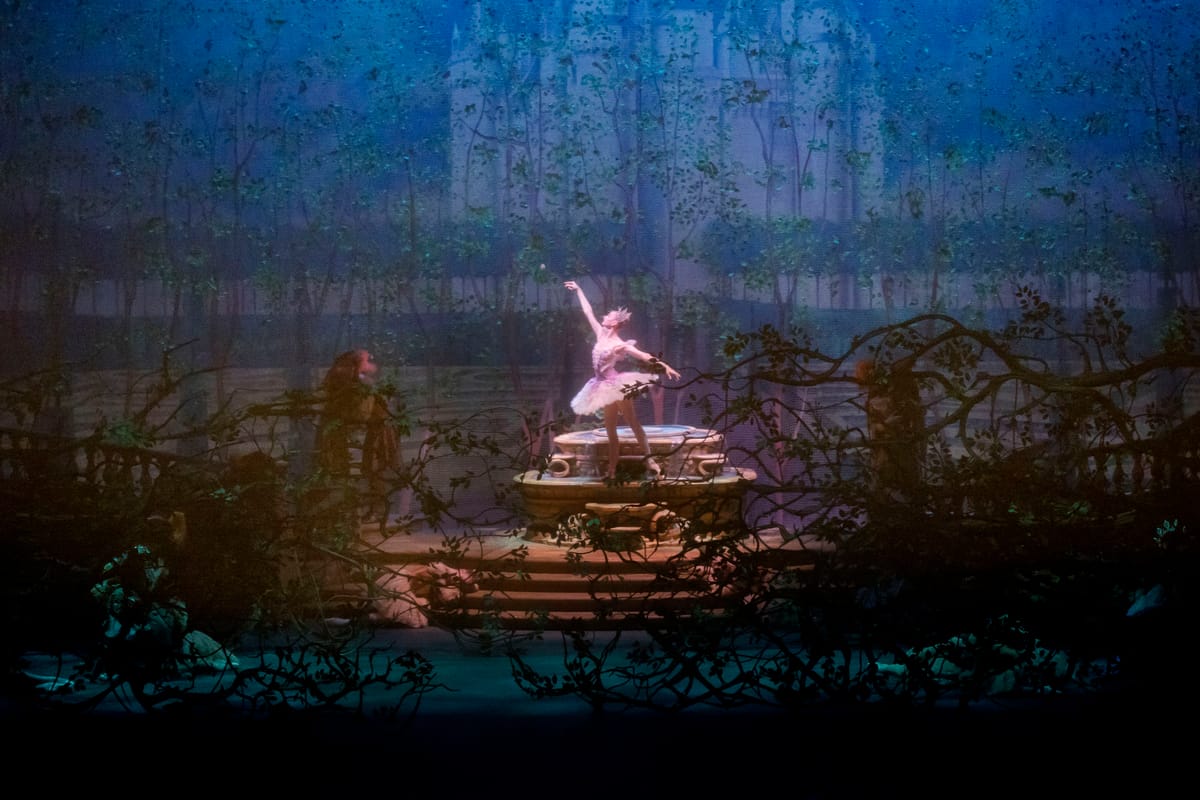

Woodward gave Martins’ poetic vision scene, with Aurora flitting through the white-clad nymphs like an enticing mist, a mysterious presence, as if she felt the Prince, rather than seeing him. She danced with a limpid clarity, floating through her solo with apparent ease, and then disappearing—it was no wonder the Prince was eager to run after her.

Chan was a noble Prince, polite yet somehow isolated from the hunting crew. It is too bad that the hunting scene is so truncated since it gives him so little time establish his character but Chan, helped by Jenelle Manzi’s controlling Countess, was able to give the Prince a warm dignity. The wedding pas de deux was both warm and dignified, though it does seem a bit cavalier of the couple to leave while their fairytale guests were celebrating, only to return after all the dancing.

Woodward put aside her happy Act I smile and moved with an inward glow; the pas de deux was both private, as the couple kept their eyes fixed on each other, and expansive, as their warmth seemed to radiate out. The highlights were all there—the one handed fish dives, the secure balances, and the fast footwork—but there was poetry as well. The solemn “My heart is yours” mime and the quiet moment after the dancing where Woodward nestled in Chan’s arms were profoundly moving and the final apotheosis combining grandeur and serenity, amplified by Tchaikovsky’s use of the French song “Vive Henri IV”, felt like a strong, if fleeting, case for monarchy.

Laracey as the Lilac Fairy was a force of nature, powerful and generous, embodying the Enlightenment’s confidence in rationality and balance, so different from the dangerous Romanticism of “Swan Lake”, where the natural world of the forest is full of evil and deadly creatures. Laracey was an unusually serious Lilac Fairy, aware that she had to work for her success, an individual and captivating approach. She used her long, willowy arms to weave a powerful spell; her careful, considered movements while conjuring up the magical rose garden were hauntingly beautiful.

Brittany Pollack debuted as Carabosse, and was a nasty piece of work, almost howling with rage, a bit over the top, but that is built into Martins’ approach. Craig Salstein, as the fussy Catalabutte, obsessively checking the guest list and then falling apart when he discovered his error (and blaming everyone else) gave a fine lesson in creating a character in a few gestures.

All the five prologue fairies were debuts; City Ballet cast corps dancers, who, given the company’s current strength, had no issues with the steps. (The previously frantic tempos of the variations were played at a more danceable speed, which certainly helped.) But the dancers didn’t fully embody the individual characteristics of their gifts and I missed some of the generous grandeur the Prologue can have. Gabriella Domini as the second fairy, Tenderness in this production, used her eloquent arms and deep curtsey to the King and Queen on her entry, pausing briefly to emphasize her gift, and the story clicked into focus.

Many of the packed Act III variations were debuts as well, and Martins has paced the act well, alternating character and classical dances. The always popular cats were Quinn Starner and Kenneth Henson (both debuts), and they scratched and rolled with a light touch. The more classical jewels (Jules Mabie as Gold, Mary Thomas MacKinnon as Diamond, Olivia Bell as Emerald, and Kloe Walker as Ruby, all debuts) had a slightly mixed success, with several unfortunate slips. Martins’ choreography for Gold and Diamond is a bit rushed and unmusical, but Emerald and Ruby are both recognizably Petipa; Walker’s Ruby was especially sparkling. And so were the Court Jesters, which Martins choreographed to the bouncy Tom Thumb music. Spartak Hoxha and Simeon Daniel Neeld were led by Alexander Perone, who tossed off some very impressive sideways split jumps with a lighthearted glee. But what I will remember longest, I expect, is Laracey’s spell, and the feeling that somewhere the Lilac Fairy is still growing a garden.

© 2026 Mary Cargill