Tis a Gift to Be Free

“POWER”

Reggie Wilson/Fist & Heel Performance Group

Ted Shawn Theater at Jacob’s Pillow

Becket, MA

July 13, 2019

When Reggie Wilson gets curious, the rest of us start to learn. Wilson’s ongoing choreographic research has delved into his African and Caribbean dance roots through multiple lenses including 20th century modern dance idioms, fractal math, and the Jewish Bible, among many. At heart, the Fist & Heel Performance Group starts with its name – the power of the fist and the heel, the enduring rhythms of the body as reflected in the movement and cultural heritage of those who were brought from Africa as slaves to the Western Hemisphere.

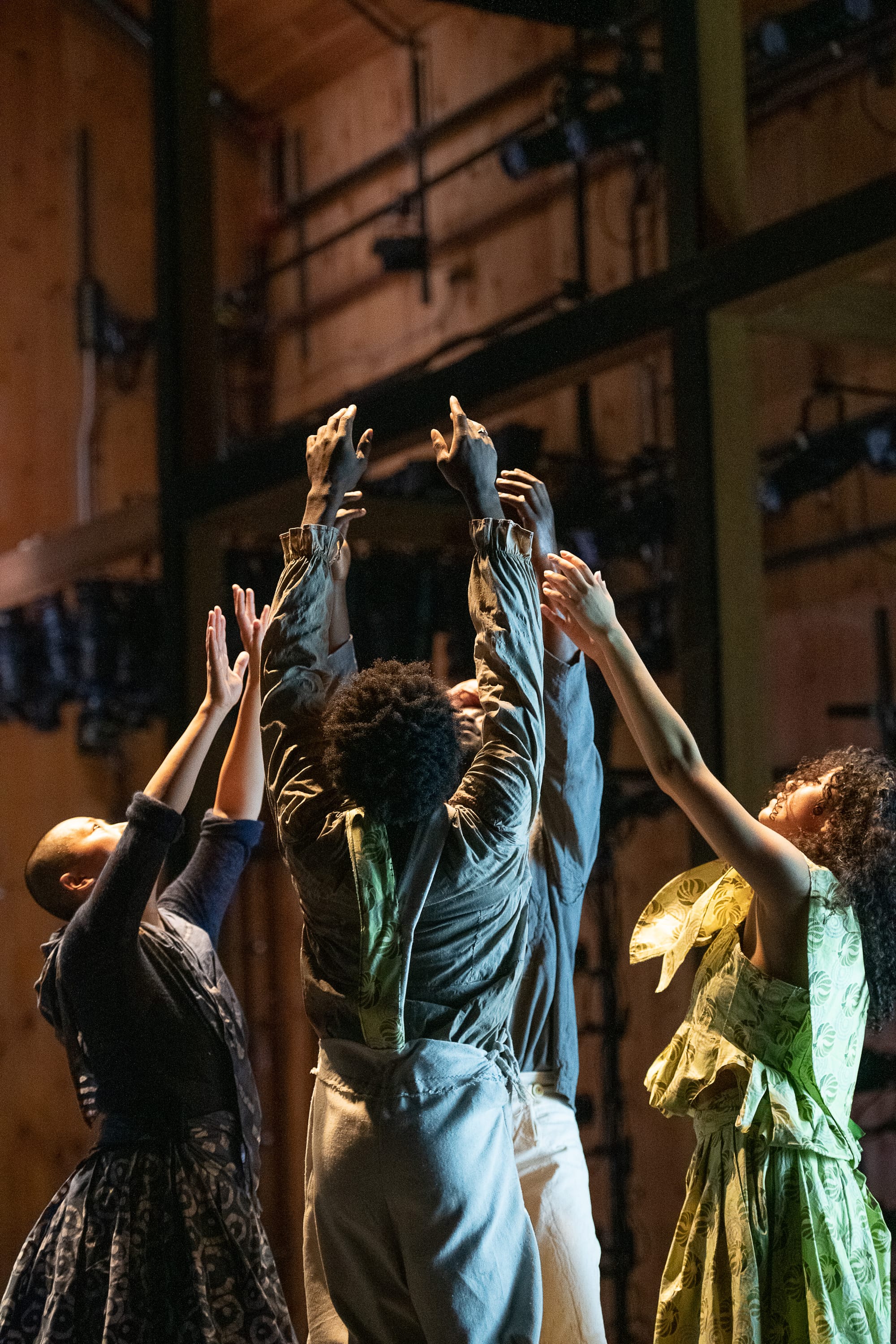

Clement Mensah, Paul Hamilton, and Hadar Ahuvia in "POWER." Photo © Christopher Duggan.

In “POWER,” Wilson turns for inspiration to the Black Shakers, a subset of the Shaker Movement that was led in the 19th century by Mother Rebecca Cox Jackson. Like more Puritan American religious forms, the Shakers focused on simplicity, celibacy, and service — but, uniquely, they also danced. Religious fervor inhabited their bodies; and that energy is the “POWER” that Wilson and his dancers embody in this new work.

In the world premiere of “POWER” at Jacob’s Pillow, Wilson and the dancers wove physical strength with spiritual fortitude, and used sound and rhythm to anchor each form. The score created immediacy by mixing traditional music with more modern sounds, all laced with the throb of drumming, clapping, and live humming. Wilson is the narrative guide in his works, a Prospero of his particular island. As “POWER” opened, he hummed as he strolled diagonally across the stage. Landing at a small wooden pew, he sat just in front and to the left of the audience; we were the congregation inhabiting the sacred space he created.

Wilson’s diverse troupe of dancers were the other participants of that congregation, and they represented a wide range of ages, races, body shapes, cultures. Joining him, off and on, to sing and drum, were his two longest running company members, each evocative and powerful movers who started dancing with Fist & Heel in the 1990s: Rhetta Aleong and Lawrence Harding. They inhabit the heritage at the core of Wilson’s choreography with a smooth grace that underpins every motion, from simple strides to their rolling turns in group dances. Often, in “POWER,” Aleong and Harding paced the perimeter of the stage, hips gently swaying and hands stirring the air, like guardians weaving safe boundaries for the dancers. After they joined communal dances, they slid back to sit with Wilson, all three acting as the keepers of the sustaining rhythms, and these “praying grounds.”

All of the dancers changed in and out of various costumes, pulling shirts, skirts, headdresses and overalls from pegs hanging in view at the edge of the stage. They shifted identities with their costumes — the layers allowing them to come from different time periods and places, moving in and out of work and church, partnering and community dances. Sun hats evoked field work; Paul Hamilton’s on and off long-tailed coat suggested a formal house servant. Every costume touched slave history, but slavery didn’t define the dancing — interior freedom did. In an early scene, Hadar Ahuvia and Gabriela Silva spun in wide skirts, their hair flying upward as their arms and hands stretched out and up, as if to heaven. The simplicity and freedom of their turning whirled spiritual energy through the space.

In the earlier stages of his Black Shaker research, Wilson created a work called “… they stood shaking, while others began to shout.” Premiered for Danspace at St. Mark’s Church, Wilson’s dancers migrated from the main church floor to the upper floor — called “slave gallery” — and moved in an ecstatic communal dance that was evoked in “POWER” as well. The traditional “ring shout” that Wilson adapted for that work also found its way into “POWER,” as the dancers moved in rhythmic, shuffling concentric circles. As one ring moved clockwise, the other was counter-clockwise, sharing the movement pattern; each of the dancers moved in their own skin, each was part of something larger than themselves.

One of their repeated patterns was of fours and eights in diamond and square patterns. What started as a traditional four-couple square dance transformed as the dancers stomped into exacting and ecstatic foot and hand claps; the couples broke from the geometry of the square into the soft edged sweeping limbs and twirls. As a community, they scooped their arms and legs up in curves, then sank down into squats and stomps, the wide skirts of the women belled out. When they kicked forward, the kicks became the start of balanced hops, one leg high and horizontal to the ground, echoing the pounding background rhythms. Their hands paddled down on empty air, then lifted heavenward with fingers outstretched. The movement propelled and echoed their collective prayer and offering.

Throughout, the dancers embodied qualities associated with the Shakers – physical fervor, separate but equal gender roles, simplicity. It was clear that Wilson had not only researched and reconstructed these ideas, but in adding his own vision and energy, he brought this culture back to a new form of life. When asked to characterize what his movement is about, Wilson has described it as “post-Africa/ Neo-Hoodoo Modern dance,” a characterization that he offers – and we accept – with a laugh and a wink. But the artist and the audience know that it is so much more. “POWER” emerged from its many antecedents; but Wilson offered a unique, innovative lens, leading us, humming and drumming, from a powerful

copyright © 2019 by Martha Sherman