Sutra

“Sutra”

White Lights Festival

Rose Theater, Lincoln Center

New York, New York

October 16, 2018

Belgian choreographer Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui’s “Sutra” is a spectacle in the true sense of the word. Created in 2008, it features monks from the Shaolin Temple in China, as well as sculpture by the well-known British artist Antony Gormley and a score, played live, by Polish composer Szymon Brzóska. Cherkaoui also performs the central role, along with child monk, Xing Kaishuo.

The monks of Shaolin are known for their martial arts, which they have perfected over centuries, first as a fighting form and then as a means of ritualized discipline. According to a program note, Cherkaoui has long been fascinated with martial arts, beginning with kung fu and then later the Shaolin variety. He also has an interest in Chan Buddhism, practiced at Shaolin. How he talked the monastery into loaning him their monks so they could tour the world, remains a mystery.

“Sutra” begins with Cherkaoui and the child seated at the side of the stage. Cherkaoui seems to be silently instructing the little boy, using gestures that weave in the air but which have no obvious meaning. A series of coffin size boxes are lined up horizontally across the stage, a sword protruding from one of them. A monk appears, pulls the sword out, and then with it, pulls another monk from inside a box. He pulls yet another monk from another box until a whole group eventually appears.

The piece then goes through a number of different phases connected by the child and Cherkaoui, who sometimes seem to be on a journey. The action alternates between Cherkaoui and/or the child moving alone, and the monks performing martial arts maneuvers alone or in unison. The child is able to execute most of the monks’ martial arts movement, which is impressive for one so young. The Shaolin martial arts style is related to traditional Chinese gymnastics, the kind one commonly sees in Peking Opera. Much of it is aerial, with leaping kicks, tumbling summersaults, flips, and backbends. Sometimes swords and staffs are used in the action.

In “Sutra” the monks also spend a good deal of time manipulating Gormley’s wooden boxes to form a variety of config- urations. At times Cherkaoui makes arrangements of miniature versions of the boxes, which the monks then emulate with the large ones. The boxes, which are open on one side, are more than props, they act as participants in the work. They can be made into a giant bookcase, in which the monks recline, or a wall, behind which they disappear. They can be arranged horizontally, as they are at the beginning of “Sutra, “or vertically, to make plinths on which the monks stand. On one occasion the monks drag the boxes about the stage on their backs, and at others they tip them over while they are inside or standing on top.

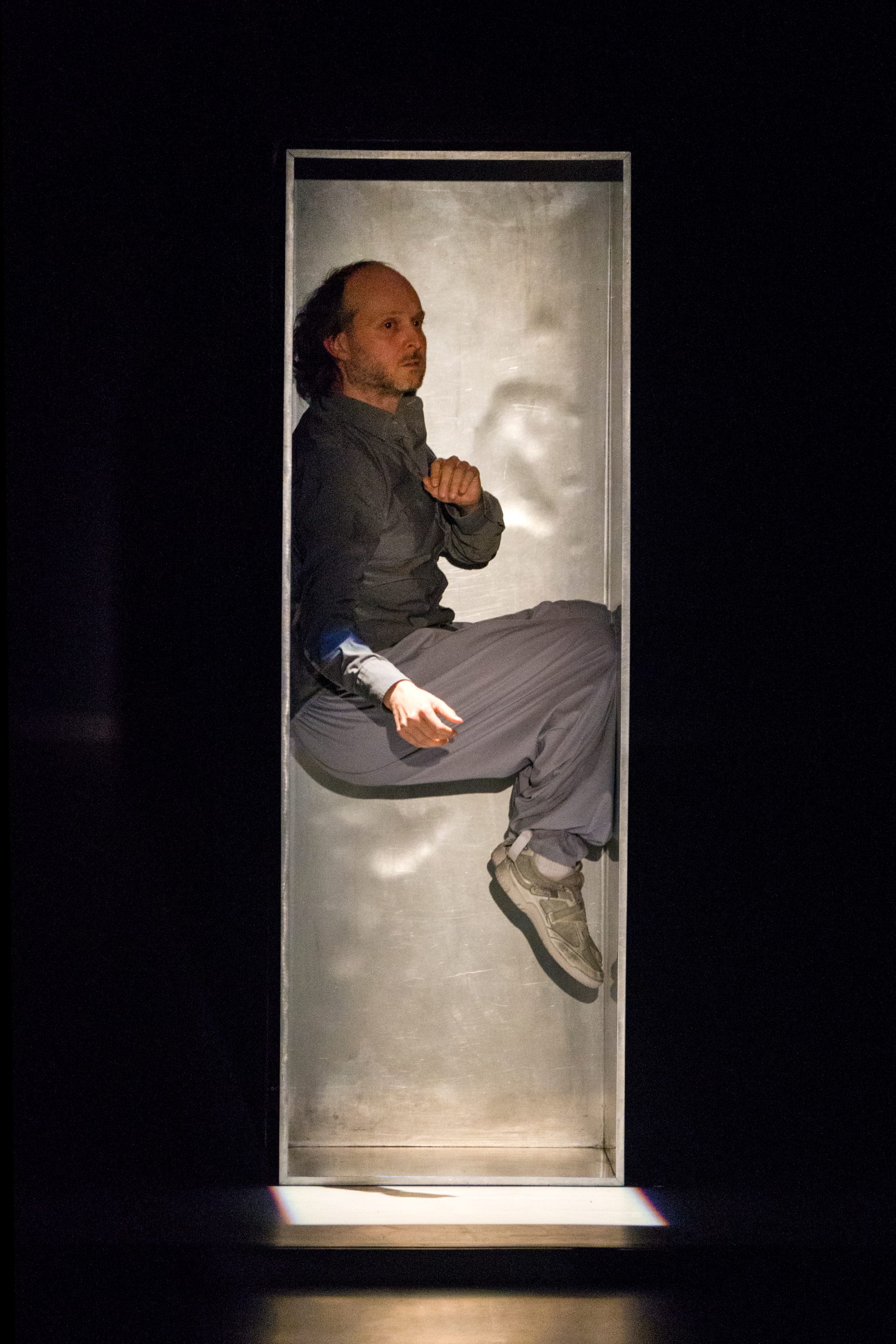

Cherkaoui has his own box, which is silver rather than unpainted wood. He is abnormally flexible and can stretch his legs into many contorted positions, allowing him to wedge himself inside his box so that he appears to be hovering in space. Eventually Cherkaoui begins to mimic the actions of the monks, as if trying to learn from them. Finally he is able to execute, at least some of their moves. The work ends on this triumphant note.

How “Sutra” holds together as a work is a matter of opinion. In my view it looks more like a series of effects rather than a coherent piece. But there is no doubt that as spectacle, it succeeds.

copyright © 2018 by Gay Morris