Play On

"The Muir", "You've Got To Be Modernistic", "Silhouettes", "Mosaic and United" (Program A)

'"The Argument", "Northwest", "Ten Suggestions", "Going Away Party" (Program B)

Mark Morris Dance Group

The Joyce Theater

New York, NY

July 16, 2025 (Program A) and July 24, 2025 (Program B)

Choreographers use music in many ways; it can provide atmosphere, humming along politely in the background, it can be a floor supporting the dancers, it can hint at a narrative, or it can weave through the dancers’ moves; Mark Morris, though, seems to use music as a three-dimensional object where his dancers exist, moving with and for the sounds, far above such mundane items like stories or flashy technique. His dances absorb the audience, helping them see and feel the music. Even at the Joyce, the home of taped music, Morris has honored the dancers and the audience with live music, showing dances set to solo piano or to chamber music (with one taped exception). There were two new works, “You’ve Got to be Modernistic”, an exploration of the Charleston by way of James P. Johnson, an early jazz pianist famous for the that dance, arranged by Ethan Iverson, who played for the performance, and “Northwest”, set to music by John Luther Adams based on traditional music of Alaskan native tribes.

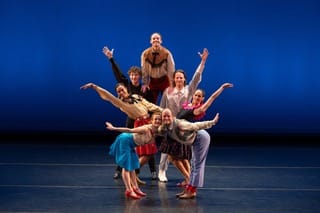

“You’ve Got to be Modernistic”, in Program A, seemed to be inspired by the 1920’s (there were echoes of the Charleston all through it), though Morris did not limit his choreography by mimicking the period. The costumes (by Elizabeth Kurtzman) were timeless; the dancers wore shiny palazzo pants with blousy tops which ripped when they moved. And how they moved! They danced fractured Charlestons, kicking exuberantly, knocking their knees, flashing their hands, and turning cartwheels as the music seemed to ripple through their bodies out to their shoulders. Both men and women had long necklaces, which they treated like hula hoops—Billy Smith was especially adept. There were so many little details, like a Popeye sailor with a spy glass motif, that need repeated viewing.

“Northwest”, in Program B, was a lyrical evocation of traditional Alaskan dances highlighting the little paper fans that the ten dancers fluttered throughout the piece. The delicate music, played on a harp and small drum, had a hypnotic rhythm echoed by the light barefoot swishings of the dancers. They were dressed casually in muddy green shorts and tee shirts designed by Amy Page, which merged into the background so the elegant lighting (Mike Faba) made the fans sparkle and the dancers looked like magnificent fireflies. They wove in and out, forming lines, circles, and groups in constantly shifting patterns that seemed timeless.

Program A opened with “The Muir” (a Scottish word meaning moor), a 2010 work set to Scottish and Irish folksongs arranged by Beethoven; these were sung live by Chloe Holgate, Chad Kranak and Julian Morris, accompanied by a violin, cello, and piano. The six dancers, three women and three men, roamed through the various moods, happy, mysterious, funny, and tragic. The program included the words of the folk songs but there were few hints of a narrative. There were brief hints of sylphide arms (so appropriate for Scotland) by the three women, though they were anything but sylph-like—Morris’s women can stand on their own. So too can the men (Dallas McMurray, Billy Smith, and Noah Vinson). I particularly enjoyed McMurray’s preening to “Sally in Our Alley”, as he dressed up to go dancing. The dancers dug into the rhythms with small prancing steps and odd, quirky gestures that seemed to have a logic and a beauty beyond meaning, ending with the haunting vignette of a woman alone mourning her dead. This was not a folksy visit to Brigadoon.

“Silhouettes”, from 1999, is set to Richard Cummings jazzy piano score, played by Colin Fowler. It is a duet, danced here by Christina Sahaida and Aaron Loux, who share one pair of pajamas, the woman getting the top and the man the bottoms. It was originally choreographed for two men, and has also been danced by two women; it is a seemingly lighthearted, floppy, and fun, with some casual ballet thrown in, beautifully danced by both; Loux especially seemed to be made of rhythm. Morris’s couple danced companionably, side by side, often doing the same steps; his couple was neither the aggressive nor co-dependent type of so many current dances, but by the end the dissonant music seemed to hint at something unsettled.

The final piece “Mosaic and United”, to Henry Cowell’s “String Quartet No. 3 (“Mosaic”) and his “String Quartet No. 4 (“United”), was also unsettled, as the angular, austere music of the first part at times veered into eerie wails, perfect for a horror film, and the softer, more lyrical second part burst with energy. The moves reflected this dissonance; the women crawled across the stage pulled by the wailing music, men stood alone looking up at who knows what, while all moved like musical notes floating in space. The odd, bouncy finale brought the cast skipping to the little hitches in the music. It is a work, like so many of Morris’s pieces, of mood and sound, floating above the words that describe it.

Program B opened with “The Argument”, from 1999; it was set to Robert Schumann’s “Fünf Stücke im Volkston”, played by Colin Fowler, piano, and Andrew Janss, cello. Four couples in chic black (costumes by Elizabeth Kurtzman) with minimal, telling gestures (how powerful a snapped head or a turned shoulder can be) live through troubled relationships, variously angry, proud, unhappy, or resigned. There are no resolutions, no final breaks or rapturous reconciliations, just a feeling that life will go on.

Mark Morris was the original dancer in “Ten Suggestions” (1981), a quirky solo to Alexander Tcherepnin’s “Bagatelles”. (The composer was the son of Nicolai Tcherepnin, who was associated with the Diaghilev company, so it seems appropriate that his music is so danceable.) Dallas McMurray, wearing flowing pajamas, wandered on stage, where he encountered a chair, a hula hoop, a hat, and a ribbon. With his hangdog look and limp, floppy somersaults, he resembled a silent film comedian exploring physical comedy with a childish glee that was both comic and touchingly innocent.

“Going Away Party” (1990) to recorded Western swing songs by Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys (their inimitable twang seems part of the scenery) is certainly comic, but not quite innocent, as there are a few raunchy moves (as when the three women, legs spread wide, hurl themselves at the men, who seem pleased but a bit non-plussed). The glossy Western costumes, including some cowboy boots (by Christine Van Loon) give the piece an affectionate tongue-in-cheek air; Morris seems to be laughing, not sneering, at the sometimes exaggerated sentimentality of the lyrics. And as always, he mines the rhythms and grace notes, sometimes quietly, and sometimes humorously, as in the final song “When You Leave Amarillo, Turn Out the Lights”—blackout, end of show. We know, however, that the show will go on again, lucky us.

copyright © 2025 by Mary Cargill