Old Masters

"Concerto Barocco", "Prodigal Son", "Symphony in C"

New York City Ballet

David H. Koch Theater

Lincoln Center

New York, New York

October 7, evening 2023

The works danced on this program are some of the oldest in the company’s repertoire—Balanchine choreographed the youngest one, “Symphony in C”, in 1947. They were also all originally created for other companies; “Concerto Barocco”, 1941 for American Ballet Caravan, an early Balanchine company, “Prodigal Son”, 1929, for the Diaghilev company, and “Symphony in C”, with the poetic title “Le Palais de Cristal”, for the Paris Opera Ballet. Only “Prodigal Son” is danced with the original designs, and the heavy, odd choreography seems wedded to Georges Rouault’s Futurist designs. “Concerto Barocco” too originally had elaborate sets and costumes (designed by Eugene Berman) but these were later dropped for practice clothes. (This was not an esthetic decision, more a lucky accident, since Berman didn’t think the sets were constructed properly and withdrew his permission.) Each movement of “Le Palais de Cristal” originally it own jewel color, and idea which obviously Balanchine reused, but when he set “Symphony in C” on his American company, there weren’t enough dancers, and everyone was in white so the corps could appear in different sections, so the white explosion of the finale that we see today is due to earlier staffing shortages.

There is no shortage in NYCB today, as the company has a number of young talented dancers. Two of them, Unity Phelan and Emily Gerrity, danced “Concerto Barocco’s” two violins, with the unobtrusive and elegant Andrew Veyette. The performance as a whole was a bit muted, with the dancers flowing through the shapes with little of the jazzy accents the Balanchine built in. Phelan and Gerrity seemed at times to be dancing for the audience, and I missed the witty sense of steps being tossed back and forth in their dances together. Those steps, though, were beautiful and Phelan and Veyette gave the pas de deux a calm and beautiful flow. Gerrity seemed to break out of the perfection shell in the third movement, and danced with a more dynamic daring, leaning back and daring her balance to fail—it certainly didn’t.

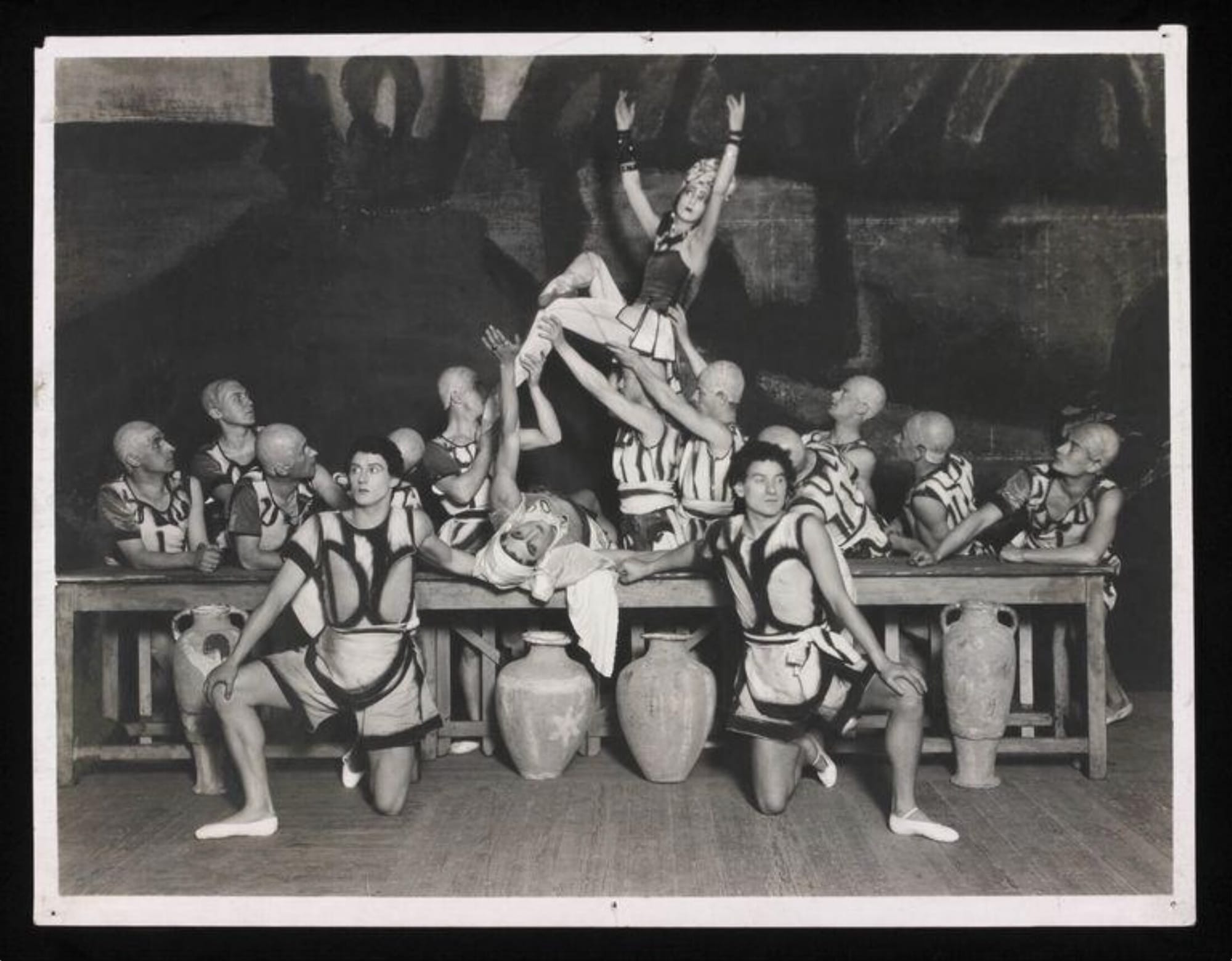

“Concerto Barocco” with its plain backdrop and simple costumes is timeless. “Prodigal Son” with is elaborate costumes, painted backdrops, heavy gestural moves, and stylized pacing, is clearly not modern, but unlike “Apollo” it is hard to imagine it being simplified or updated. The production looks much like the original and though it is sometimes dismissed as dated, it does give the dancers an opportunity to create power through stillness and to expand their power. Daniel Ulbricht and Miriam Miller were the odd couple, and Preston Preston Shamble debuted as the Father.

Ulbricht was a willful prodigal, yearning for the outside world, resenting his limited outlook. His jumps exploded in frustration, shoved his Father’s restraining hand away without hesitation. His Prodigal wasn’t just an innocent trapped naif, he seemed eager to try anything, but was originally a little frightened of the goons, an interesting hint of weakness, and gave them his possessions out of fear rather than trusting generosity.

Miller was a young looking Siren; she is tall but slight and has a beautifully sunny aura which gave the moment when the Siren pounds her chest in an apparent paroxysm of guilt finally seem plausible though she recovered quickly and went after the poor Prodigal, though I did miss the smoldering gleeful venom of more practiced Sirens. Ulbricht’s humiliation and despair alternated between a powerful stillness and sudden movements, falling with a shattering crash when he could no longer stand. His final crawl was slow and painful, done without melodrama and his encounter with his Father was unusually uneasy, as if he weren’t sure of his reception. Chamblee gave the father a stern but rather frightening dignity. He came more downstage for his son’s return than I remember others doing, watching the poor boy carefully as if deciding whether or not to forgive him. Ulbricht had to climb into his arms by himself until finally Shamble slowly gathered him in. It was a very effective and powerful moment.

“Symphony in C” is packed with effective moments though the 2012 costume redesign is unfortunate. The stiff tutus have a distracting accumulation of grayish crystals around the stomach and the poor men look like they are encased in rhinestone breastplates—the program thanks Swarovski for its support for the new costumes. Megan Fairchild, with Joseph Gordon, danced the opening movement with a regal authority and graciousness, opening her arms so generously and footwork was fast and clear. Gordon was her elegant partner, with explosive turns and clean jumps.

Sara Mearns, with Tyler Angle, danced the melancholy second movement. She seemed to have a bit of trouble with her balances, though Angle covered well. But her dancing seemed to go far beyond steps, and she moved, eyes downcast, in a world of her own through that plangent, haunting music, an Odette in excelsis. It was drama without narrative or meaning, pure feeling and pure beauty and was a true privilege to watch.

It was also a privilege to was the blazing third movement, where Emma von Enck and Roman Mejia made their joint debuts. They were well-matched, soaring through the jumps and turns with a joyful abandon. They have both been having wonderful seasons, and both seem to brighten up the stage whenever they appear, dancing for the sheer thrill of moving and eager to share the fun with the audience.

Indiana Woodward and Troy Schumacher danced the fourth movement. She had an unfortunate slip and fall but recovered with apparent aplomb and I missed the quick little leg kick that accents the opening turns, but her smooth, elegant upper body was lovely. Schumacher barely gets a leg in before the rest of the dancers pour in for the glorious finale, but he partnered her graciously. The finale looked glorious with its shifting geometries; a true old master.

copyright © 2023 by Mary Cargill