New and Old

First Program: "Vive la Loïe", "Takademe", "Solitaire", "Company B"

Second Program: "Sunset", "Under the Rhythm", "Beloved Renegade"

Paul Taylor Dance Company

David H. Koch Theater

Lincoln Center

New York, NY

November 12, 2025 (first program) and November 13, 2025 (second program)

The Paul Taylor Dance Company is facing the same questions that other companies whose repertories are based on the founding choreographer are facing—how to continue when the source of new works is no longer around. The Cunningham company shut down, preferring its memories to possibly diluting its material, but others have continued by combining so-called heritage works with those of new choreographers. This is the route Taylor planned; in 2014, he renamed his company the Paul Taylor American Modern Dance and added several older works by other modern dance choreographers. (The company is currently called simply the Paul Taylor Dance Company, but it has continued to add classics of modern dance, most recently, in 2022, Kurt Jooss’s “The Green Table”.) In 2018, Paul Taylor appointed the dancer Michael Novak as the artistic director designate, and in 2022 Novak appointed the ballet dancer Lauren Lovette the Taylor Company’s resident choreographer and in 2024 appointed Robert Battle, formerly directory of the Alvin Ailey Company, as an additional resident choreographer.

The oldest choreographer performed is Loïe Fuller (1862-1928), or rather Jody Sperling’s 2024 homage to the Art Nouveau heroine’s use of color, fabric, and the then revolutionary electric light. In “Vive La Loīe” Jessica Ferretti stood on a light box wearing a voluminous white silk gown which extended from poles attached to her arms and to Max Richter’s recomposition of Vivaldi’s "The Four Seasons” started manipulating the fabric while the lights turned her dress into a Northern Lights show. She became a butterfly, a flower, the Winged Victory, a revolving mass a shapes, at times lyrical and at times triumphant and at all times creating stunningly beautiful forms.

Robert Battle’s “Takademe”, choreographed in 1999, had its Taylor debut this year. It is another brief solo, created originally for a woman but danced by both sexes. Novak has given it to both the very tall, very strong, and very imposing Devon Louis, and the very small, very strong, and very dynamic Payton Primer (I saw Primer). Its explosive moves are based on Indian Kathak dance and performed to a recording of Sheila Chandra, from her "Speaking in Tongues II”, a sharp, rhythmic collection of syllables which the sharp, rhythmic moves amplify. Battle incorporated the Kathak use of the heel, the wrist, and the eyes and added some powerful jumps and, he has explained in interviews, a Michael Jackson feel with leg snaps and head moves. Primer dominated the stage, in complete command of the spiky, quirky, precise choreography— even her head bobbles were perfectly timed.

Lauren Lovette’s 2022 “Solitaire”, subtitled “a gem set alone” was not a solo, its cast of thirteen danced tirelessly through Ernest Bloch’s “Concerto Grosso No. 1”. The stage design (sets and costumes were by Santo Loquasto) was striking, a large triangle with Art Decoish stripes coming to a point; its elegant stylization did not seem to go with the drab beige outfits that the dancers wore, and it vanished towards the end of the dance. Presumably, since solitaire is, among other things, a jewel setting, its disappearance was meant to symbolize the solitary man who finally found some friends.

Alex Clayton was the lonely fellow; he had an long, intense solo, full of rising and falling, twitchy moves (even his back muscles seemed to have minds of their own), and unusual turns and balances. His performance was a technical tour de force, but it was evoked adrenaline rather than emotion. Lovette never let him pause so his thoughts and feelings could resonate and I got the impression he may have been left alone because he wouldn’t stop talking.

Eventually he was joined by the larger group for a get-together while he had a brief duet with Lee Duveneck which seemed to fizzle out when Gabrielle Barnes joined them. The finale was bright and energetic, with several dancers prancing through the loping Taylor runs, as if they were looking for “Esplanade”. The dancers certainly gave it their all, and looked strong and engaged, but it was a bit hollow.

Battle’s first work for the company as resident choreographer, “Under the Rhythm” premiered this season, is also a mixture of styles. He used a variety of recordings; there were excerpts from Damian Bassman, Ella Fitzgerald, Wycliffe Gordon, Mahalia Jackson, and Steve Reich. The work had a variety show feel, tied together by the corps dressed by Santo Loquasto in white shirts, black trousers, snappy suspenders, bowler hats, and blazing white spats that reflected the light, who chugged in and out of the various acts, often with perfectly synchronized mechanical arm movements. The dancing was astounding, strong and vibrant, but somewhat impersonal, as various soloists emerged, performed, acknowledged the raucous applause, to be followed by another apparently unrelated act.

Patrick Gamble was especially strong in his solo set to Reich’s “Clapping Music”, lowering himself to the ground and then exploding upwards. Duveneck and Clayton had a jazzy verve and a great time playing at being the Nicholas Brothers. A more somber Jessica Ferretti and Devon Louis gave their slow, bluesy pas de deux a slightly wary edge, like a couple who had endured too much. Jada Pearman was buoyant and beaming as she danced to Mahalia Jackson singing “Down by the Riverside”; she could have bounded over from “Revelations”. These vignettes were stylish, musical, and distinctive, but the work didn’t really hang together as an expressive whole.

The three Taylor works, “Sunset” (1983), “Company B” (1991), and “Beloved Renegade” (2008), on the other hand, are rich, coherent, and moving. All of them involve death and dying soldiers, though the moods vary from “Sunset’s” lyricism, “Company B’s” bravado, and “Beloved Renegade’s” resigned acceptance.

Taylor used a combination of Edward Elgar and loon calls to create a haunting vignette of four girls in white summer dresses and six soldiers in Alex Katz’s abstract park as they danced and flirted with a lilting innocence before the men go off to war in some unnamed location (the loon sounds evoked a jungle atmosphere). The girls emerged as angelic comforters, nursing the fallen soldiers, then, returning to Elgar, they were back in the park, the girls watching the soldiers leave as a red beret falls to the ground, a reminder of the dead soldier. Taylor’s solemn restraint avoided any sentimentality.

Lee Duveneck and John Harnarge danced the main characters, a vivid portrait of male friendship. Taylor included everyday gestures—hands in pockets, tie straightening, buttoning shirts—to create ordinary guys, people the audience felt they knew. The dancing was not always smooth, and Duveneck did have some white knuckle moments helping Madelyn Ho up the human pyramid, but the overall effect of the work was haunting.

“Company B” too, full of fallen soldiers and popular 1940 ballads (it is set to recordings by the Andrews Sisters), combined upbeat music with falling soldiers. There was comedy—Duveneck was a hapless bespectacled Johnny, and Payton Primer undulated enthusiastically through “Rum and Coca Cola”. But there was, as one of the songs says “much disillusion there”.

Clayton in “Tico Tico” danced with a cocky bravura, as if smoothing his hair would stop a bullet. It didn’t. Nor could Harnage’s bugle help him outrun the guns. Devon Louis was especially moving dancing with a lyrical Elizabeth Chapa in “There Will Never Be Another You”. Louis has a phenomenally strong technique, but at times he can hide behind it but here he moved simply and openly as the ghost lover vanishing from sight; the air around him seemed to shimmer.

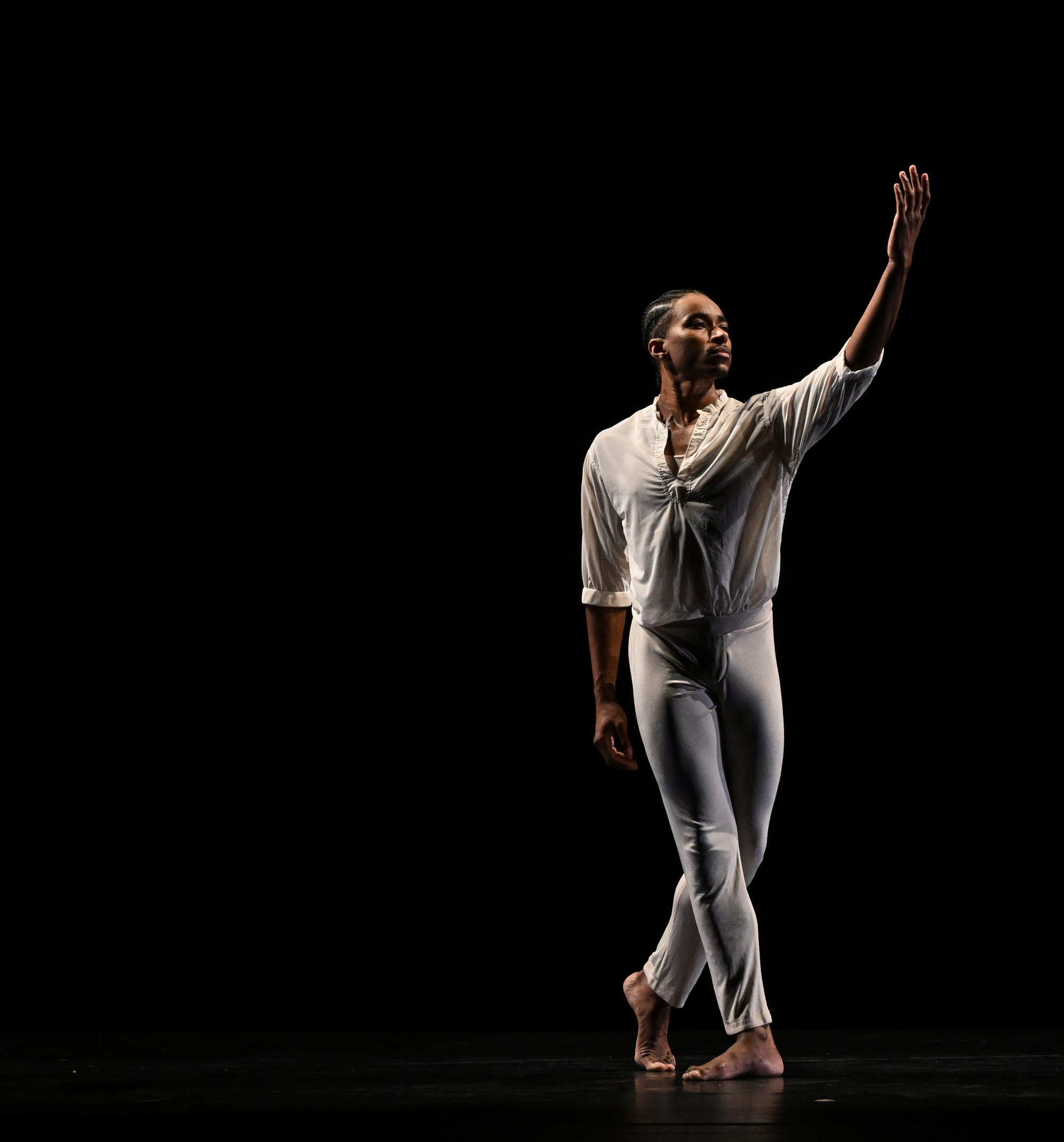

Louis also danced the Walt Whitman figure in Taylor’s “Beloved Renegade” (2008). Set to Francis Poulenc’s “Gloria”, this multilayered late work combines religion with poetry (each of the six sections is given a phrase from Whitman). Taylor, an avowed atheist, seemed to find comfort in the religious ritual, while believing in the power of the artist. The main character, seemed to be a combination of Whitman, Taylor, and Everyman, watched episodes of his life in a seemingly random order. We saw children playing, a happy couple, men dying who were comforted by Louis (Whitman had been a nurse during the Civil War). Taylor created the main role for his long-time dancer, Michael Trusnovic, whose slightly world-weary, magnetic presence dominated the work. Michael Novak, too, though much younger than Trusnovic, gave the role a watchful gentleness. Louis’s eager, youthful presence did lack some of the powerful retrospective resonance but his dancing with Elizabeth Chapa, as an angle of death, was magnificent.

Chapa, in a beige body-stocking, was both impassive and welcoming, moving like a marble statue through the work. Her steady revolving attitudes looked like a figure of Mercury come to life—one of Mercury’s functions, after all, was to guide souls to the underworld. The final Whitman phrase Taylor chose was “I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love, if you want me again look for me under your boot-soles”. Lovette and Battle choreograph for astounding dancers, while Taylor choreographed for people who also danced. If we want Taylor again, we can look at the dancers performing his works.

copyright © 2025 by Mary Cargill