Judson Dance Theater

“Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done”

Museum of Modern Art

New York, New York

September 16, 2018 – February 3, 2019

The canonic status of the Judson Dance Theater was secured nearly forty years ago with Sally Banes’ two studies, “Terpsichore in Sneakers: Post-modern Dance” and “Democracy’s Body: Judson Dance Theater, 1962-1964.” The handsome exhibition that the Museum of Modern Art has mounted does not question Judson’s place in the canon, although in certain details it expands on it. In other words, the show is in no way a re-evaluation or revision of the standard Judson narrative, but a celebration of it. As a whole, MoMA has demonstrated a remarkable commitment to the show (which, after all, concerns dance more than visual art) with an abundance of performances, symposia, and events surrounding the exhibition.

Since art museums are in the business of collecting and displaying objects, it is not surprising that MoMA emphasizes films, photographs, and documents pertaining to the group. But curators Ana Janevski, Thomas J. Lax, and Martha Joseph have gone beyond this usual format by adding a performance series of Judson dances, many of them overseen by the original choreographers. These include concerts of works by Yvonne Rainer, Lucinda Childs, David Gordon, Deborah Hay, and Steve Paxton along with frequent demonstrations of Simone Forti’s construction pieces. Included, too, are film programs on all these choreographers and on Trisha Brown, whose company appears at the Brooklyn Academy of Music this week in early works. From a dance perspective, the performances may be the most illuminating element of the MoMA show. Since the concerts featuring individual choreographers are given in tandem through January, the focus here is on the films and objects being displayed.

From 1962 to 1964, Judson Memorial Church in Greenwich Village served as the base for weekly workshops and the first sixteen concerts of the Judson Dance Theater, accounting for the group’s name. From the beginning the Judson members included composers and visual artists as well as dancers, most prominently Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Morris. Although each member presented his or her own work, decisions were made by consensus, and members regularly contributed to each other’s pieces. This was a marked contrast to the way modern dance companies were organized and was an indication of the experimental and rebellious nature of the group.

The exhibition is arranged thematically, with sections that highlight elements that concerned the Judson members, including props, scores, process, improvisation, and ordinary gestures. As mentioned, this show follows the standard story line of Judson without much further digging. Although attention is given to some of the artists, writers and composers, mostly in Greenwich Village, who interacted with Judson, we learn next to nothing about the dance tradition from which Judson emerged, except immediate influences such as Merce Cunningham, Anna Halprin and James Waring; of what exactly the group was rebelling against and why; of Judson’s broader ties to modernism and the historical avant-garde; or of Judson’s legacy. Nor are we given any idea of what other vanguard dance was going on in New York in the early 1960s. One would be forgiven for thinking Judson was the only dance group doing experimental work in New York at the time.

What the show does do is document many of the concerns of the Judson members, which were overwhelmingly formal. Among the questions they were asking were: What kind of movement can constitute a dance, how can a dance be organized, what are the limits of dance? They were seeking alternatives to narrative, theatrical effects, and symbols, which had come to dominate modern dance, and which compromised the genre’s credentials as a modernist form. In giving attention to the formal essentials of what constituted dance, the Judson dancers were modernist, rather than postmodernist, a term that has often been used to define them in the dance literature.

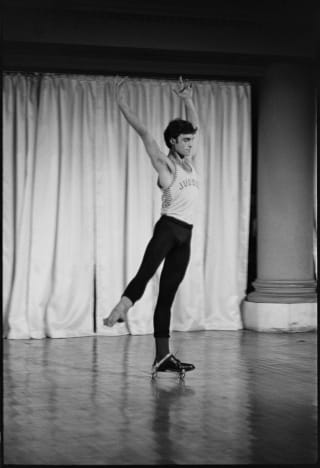

The MoMA exhibition emphasizes these formal concerns in written and visual documents, without getting into the modernist/ postmodern- ist debate that has been important in the dance world. There are examples of posters and written concert programs; scores used to give instructions or suggestions for dances; photos of dances improvised or based on tasks, danced in everyday clothes and incorporating everyday movement. However, the show also makes clear that the dancers, despite explorations in conventional movement and the incorporation of non-dancers like Rauschenberg and Morris in their concerts, were themselves trained in modern dance and/or ballet. A photo of Deborah Hay’s “Would They or Wouldn’t They?” (1963) illustrates how the artists often juxtaposed established dance techniques with quotidian movement.

Particularly interesting are archival films and videos set up on giant screens arranged around the exhibition space. Among them is a film shot in 1964 by Gene Friedman entitled “Three Dances.” It juxtaposes moving images of visitors strolling through MoMA’s sculpture garden (“Public”), Judson members doing the twist in the basement of Judson Church (“Party”), and dancer Judith Dunn warming up alone in her studio (“Private”), which together give a Judson answer to the question, “what can be a dance?”

Another film, this one by Andy Warhol, shows Village Voice critic Jill Johnston, a major supporter of Judson, and Fred Herko dancing on a rooftop while they occasionally smoke cigarettes and swig beer. The film stresses the Judson artists’ youth and the atmosphere of freedom and playfulness in which they operated.

Yet another film documents a work by Robert Morris entitled “Site,” in which he stresses the labor of making art. Dressed in workmen’s clothes and gloves, he moves screens about to reveal or conceal a nude Carolee Schneemann posed as Manet’s “Olympia.” It is instructive to see how different Morris’s aims are from those of the dancers. Although part of the group (Morris was married to Simone Forti and was later Rainer’s lover), his viewpoint is that of a visual artist, not a dancer. To begin with, his reference in the piece is to art history and the tradition of the artist and his model rather than to dance history. More important, Morris is less interested in how movement might count as labor, than in how the artist may manipulate objects and what that does to them. The body is one more object, particularly the woman’s body.

“Site” contrasts with a group of constructions Forti designed as props for dancers to use. These include a see-saw (a wooden plank on a saw horse), plywood boxes, an inclined plywood sheet and ropes. These props were used in conjunction with various tasks and improvisations, but the emphasis was on how the dancer related to the prop through movement, not on the prop (or the dancer) as an object. Sitting in the museum and unaccompanied by dance, the constructions resemble minimalist sculptures, similar to those that eventually made Morris famous, but their purpose was totally different, pointing up the difference between visual and dance aims—one on the manipulation of objects, one on human movement. MoMA wisely brings Forti’s objects to life through her dances, which are being presented at various times each week during the course of the show.

There is a ghost that haunts the MoMA exhibition, and from today’s vantage point it is glaringly obvious. The Judson group was overwhelmingly white and, because of its engagement with formalism, its members ignored the racial and gender revolutions that were building around them. Everyday movement might be incorporated into dances, but only if it made no reference to anything beyond itself. To have made an allusion to the momentous events that were beginning to convulse society would have been to compromise the modernist ideology to which the group was dedicated. It is significant that when dancer Elaine Sommers scattered newspapers around the floor of Judson Church, her dance took its cues not from the news but from the abstract patterns made by the layout of images and text. This rejection of the political paradoxically created a vanguard that was in one sense conservative, and it makes the Judson group’s dances appear today as formally important but limited in scope.

On the other hand, the MoMA exhibition emphasizes how the Judson group, in the two years it existed, was truly experimental, and attractively unpretentious. The members’ dances were not aimed at audience consumption or at scandal (despite some nudity), as much as at problem solving. This owed a great deal to the workshop environment in which dances were created. Compare Judson performances to those of earlier vanguard groups, such as the futurists, and the Judson works appear, if anything, refreshingly unselfconscious, even innocent. The group’s concerts were mainly attended by friends and colleagues, who were less like paying customers and more like neighbors dropping in to see how the work was going. Of course such an experimental phase doesn’t last, and the Judson Dance Theater, at least in its original form, soon broke up. Some of its members went on to become famous choreographers, some dropped from sight. Judson was a moment, and once that moment was over, experimentation gradually hardened into style. Judson’s most important legacy lay in asking: What qualifies as dance? In exploring that question, the group opened the gates to a much more inclusive and democratic definition than had existed before, and one that has greatly enriched all aspects of the dance field.

copyright © 2018 by Gay Morris