Bodies in Motion

"Body of Work", "Rhapsody", "Silent Screen"

The National Ballet of Canada

Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts

Toronto, Canada

November 9, 2024

The National Ballet of Canada returned home looking energized after touring in London and Paris last month. They opened their Toronto season with a mixed program designed to attract classical and contemporary ballet fans alike. No classicist could resist Sir Frederick Ashton’s “Rhapsody”, a dazzling exemplar of bravura technique. Created for the legendary Mikhail Baryshnikov, it remains one of the most stunning (and challenging) ballets in any company’s repertoire. “Rhapsody” was paired with “Silent Screen”, the first work from prolific choreographic duo Sol León and Paul Lightfoot acquired by the NBoC. “Silent Screen” marries film and dance, blurring the lines between them and showcasing León and Lightfoot’s unique contemporary style. Rounding out the program was a solo choreographed and performed by principal dancer Guillaume Côté, “Body of Work”, as part of his farewell season (he will retire in June 2025 at the end of the 2024-2025 season).

“Body of Work” was created for the Governor General’s Performing Arts Award gala in 2014 where Côté’s friend and mentor, Anik Bissonette was being honoured. Set to the transcendent second movement of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7, this five minute solo builds in intensity, mirroring the arc of a fulfilling artistic career. The set (standing lamps on an empty stage) and costume design (black pants designed by former NBoC dancer Krista Dowson) are simple so as not to distract from the movement quality itself. Some of the most striking moments are those of stillness and isolation of small gestures. The piece begins with Côté standing with his back to the audience, facing a light ahead of him, arms wide like Atlas. The image is reminiscent of his performances in George Balanchine’s “Apollo”. That visual then morphs as he begins to undulate his arms, creating a rippling effect, an androgynous variation of Michel Fokine’s “Dying Swan”. It is a whirlwind tour of different eras of Côté’s dance journey, mixing classroom steps with bursts of virtuosity and moments with the groundedness of contemporary dance. He brought both pathos and a sense of triumph to the piece, giving it dimension and dynamics.

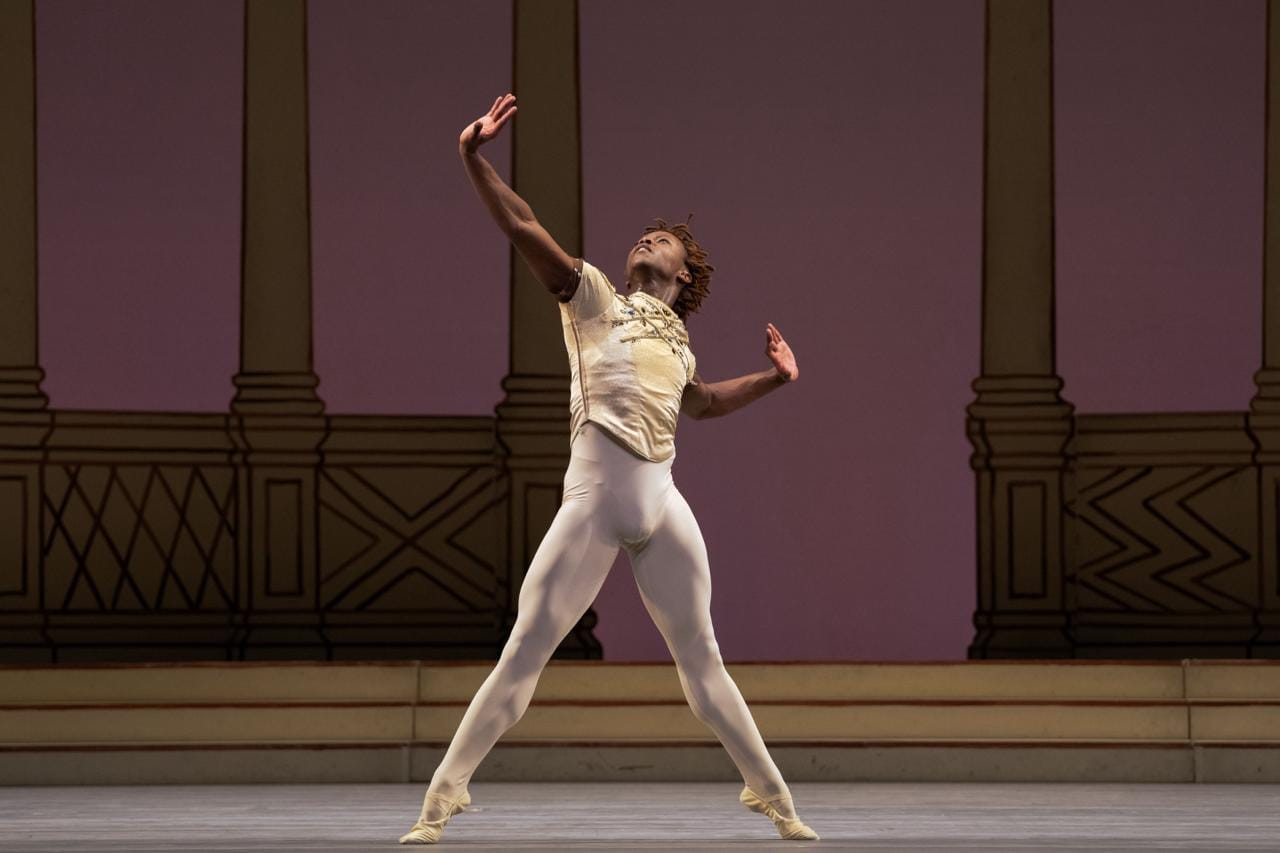

Next was “Rhapsody”. With Siphesihle November and Tirion Law in the leading roles, this joyous ballet was in excellent hands. They truly embodied Sergei Rachmaninoff’s grand “Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini”. Originally created as a vehicle to highlight Baryshnikov’s strengths, the choreography is fiendishly difficult with intricate jumps, dizzying series of turns and rapid weight transfers. It is extremely exposing for even the most assured technicians. Nonetheless, November managed to look totally calm and relaxed the entire time, which is quite impressive. Initially, he looked a bit subdued, almost tired. But this was short lived. It became evident he was pacing himself and the amplitude of his movements swelled with the crescendos of the music. His jumps landed softly and his turns were clean and centred, stopping on a dime. He had the right attack needed for this ballet and was able to infuse it with his signature boyish charm and jazzy inflections. The hip swivels and more pedestrian movements had shades of his recent performances in “Rubies” earlier this year. He showed tremendous strength and endurance, gradually extending his arms in an overhead lift with Law (towards the end of the ballet), really presenting her instead of just popping her up.

Law more than held her own. The quick allegro steps seem to come naturally to her – she is often cast in soubrette roles. But in the adagio sections, she became bigger, her extensions and use of space giving the illusion that she was taller than her 5 feet and 2 inches. She made each backbend poetic and meaningful, luxuriating in the movement. Her balances were suspended and weightless. Rather than dancing to the music, she made it appear as though she was making the music happen with each gesture. She breathed with the orchestra.

The corps of six couples was also dealt very difficult choreography and fared well with it overall. The men looked a bit stressed during the petit allegro, especially the section where they do a variation of entrechat quatre with a wide separation of the legs before the beats. During those more challenging passages, I did notice they lost their connection with Ashton’s épaulment and carriage of the upper body. Hopefully with more runs, these details will get ironed out. NBoC pianist Zhenya Vitort deserves a special mention for her beautiful rendering of Rachmaninoff’s score. November, ever a gentleman, gave her his bouquet of flowers during the curtain calls.

The finale of the mixed program was León and Lightfoot’s “Silent Screen” set to music from Philip Glass’ “Glassworks” and “The Hours”. Toronto audiences will recognize some of the music from Jerome Robbins’ “Glass Pieces”, last seen here in 2009. “Silent Screen” premiered in 2005, before the trend of using film projections in ballet had really taken off. Lately it does feel like almost all new ballets have some sort of film component from “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” to “MADDADDAM” to “Le Petit Prince”. Sometimes adding film to dance can be distracting and unnecessary. However, when used well, it can heighten a work’s visual impact dramatically. Other than Côté and Robert Lepage’s “Frame by Frame”, there is no other ballet in the NBoC repertoire that uses film so inventively and effectively.

For instance, in the first scene, we see three figures standing and looking out at the sea. They are motionless, posing in a tableau while the background is moving. It is purposely ambiguous whether they are part of the film or appearing live, and only becomes evident when two start walking down stage. It is a clever optical illusion. Later the film guides the dancers through a forest, a starry sky and a close up of a window, as well as more abstract settings that represent an inner world.

“Silent Screen” has a universal appeal. There are archetypal characters in different scenarios but everything is open ended enough that one can project almost anything on them. There is a couple dressed in black (Christopher Gerty and Hannah Galway), somber and at odds with one another at times and at other times totally connected and moving in perfect unison. There is a second man (Ben Rudisin) that brings a somewhat menacing and sinister energy. There is a young girl in red that appears in the film (played by Lightfoot and León’s daughter) and later reappears in adult form (Emma Ouellet). There is an energetic pas de deux for a youthful couple in white, filled with soaring lifts and even a supported handstand (Shaakir Muhammad and Erica Lall, two of the newest members of the corps de ballet). There is a mysterious woman with a giant black skirt who rises from the orchestra pit with her skirt blowing dramatically in the wind (retired NBoC principal Xiao Nan Yu appearing as a guest artist). We are not told who these characters are, yet there is something so familiar about each of them.

Lightfoot and León have a very distinctive choreographic style. Perhaps because they work collaboratively and come from quite different backgrounds, the range and variety in their movements is vast. Nothing ever feels predictable and this makes their work exciting and eminently watchable. For long stretches, the choreography does not travel much. The dancers stay in the same spot, perhaps not to obstruct the film. Normally, this would be a problem, yet there is so much going on that one barely notices. Everything is choreographed down to the facial expressions and at times, vocalizations and onomatopoeia. In interviews, Lightfoot and León mention being inspired by the silent film era with its exaggerated facial expressions and use of body language to tell a story. They have the dancers frequently screaming silently with dropped jaws and wide eyes - pantomime for modern times.

copyright © 2024 by Denise Sum