An Isadora Duncan Education

“Isadora Duncan”

Jérôme Bel

FIAF “Crossing the Line” Festival

Florence Gould Hall

New York, NY

September 25, 2019

The purity of Isadora Duncan’s simple, powerful movement and vision was represented with gentle ardor in Jérôme Bel’s framed portrait of the iconic dancer. “Isadora Duncan” was danced, in its US premiere, by Catherine Gallant, a long-time student of the Duncan technique, but the event was as much lesson as a performance. Using the program’s simple structure, Gallant offered the once groundbreaking work as a parade of metaphors. She danced movingly; and by evening’s end each audience member could interpret Duncan’s dances as if they had learned sign language or braille for the choreography – less mystery, more specific, flowing meaning. In its unadorned way, a century after its creation, the movement still speaks.

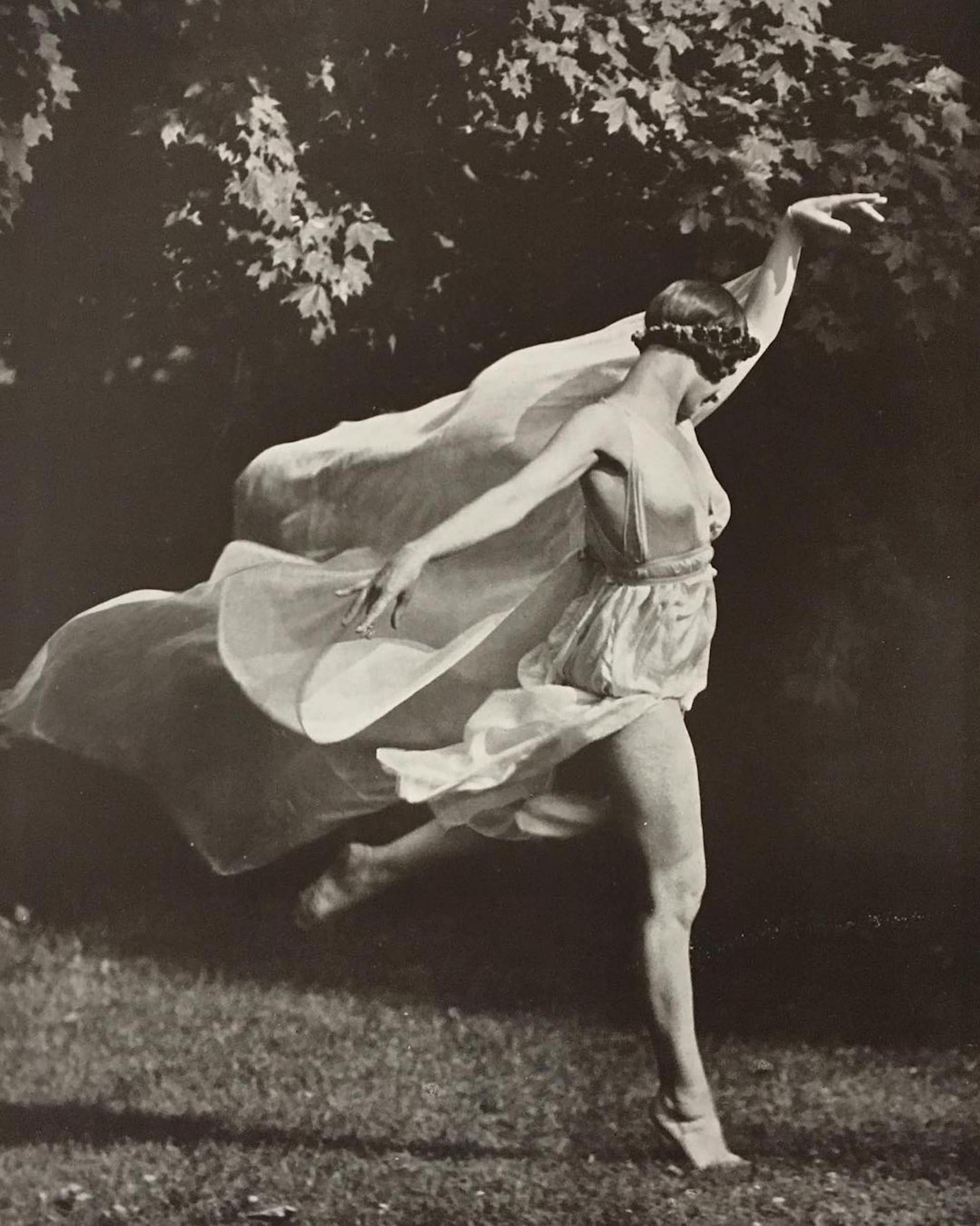

Catherine Gallant in "Isadora Duncan." Photo © Elena Olivo.

Duncan’s style was revolutionary for its time (she was called “the mother of dance;”); she was a pioneer for freedom in movement. The movement grew from images that Duncan was drawn to, particularly Greek imagery and the ocean. For the first danced work, Duncan's early “Water Study,” Gallant described the motions as she danced them: splash, break, spill, dive, emerge. Her arms made the waves apparent and alive. The few photos and images of Duncan dancing were these images, the rise and fall of arms, the high knees of her transporting skip, the flow of hair and neck, the soft contours of the dancer’s spine, the flowing fabric. Gallant’s costume (a revealing Greek-style sheath) and bare feet were also the simple images we have of Duncan.

The hour-long program followed a simple pattern, a series of lecture-demonstrations based on a classic of teaching strategy: show, explain, show again. Gallant narrated the dance with a timeline of Duncan’s bohemian life, from childhood until her well-known and dramatic death at age 50. Punctuating the biography were four dances, each representing a stage in the evolution of Duncan’s choreography and of the priorities in her life.

For each dance, Gallant also interpreted, and like a good audiotape accompanying art in museums, Gallant’s patter was informative and well-paced. The chance to “see for ourselves” was offered first – then, Gallant named and demonstrated each image. We saw the third iteration of each dance through Duncan’s (and Bel and Gallant’s) lens. Though lovely, it was simplistic for those with some dance knowledge.

When Gallant danced “Prelude,” to the very familiar Chopin Op. 28, No. 7, her narration translated the dance into concrete poetry. Her arms swept up and her weight slowly shifted, eyes gazing up, and she softly droned to each movement shift: “I wonder. Is it here? Search. Come back to myself. Maybe the Sky.” As her arms opened to the heavens at the work’s end, she murmured,“It’s here.” This dance lasted only a few minutes, like each of the dances in the evening; this one was a visible poem to Chopin’s accompaniment.

Between the first two and last two dances, Gallant invited audience members to the stage to learn some of the movement; many took her up on the offer. As she taught Duncan patterns to the class on-stage, she also invited the audience to dance from their seats, if they wished – to find our breath, to feel the energy being taken in and sent out, to make contact. Even seated, Duncan’s principles could be exercised.

The physics of the movement was uncovered when the participants learned to use the weight of their thighs to skip a la Duncan. Gallant taught the class to “fly and land,” to “surge, spill, plunge,” building on the many metaphors she’d already shared. When she asked her students what they wanted to learn of the movements in the first two dances, everything was fair game – Gallant led the class into several of those images as well. “Teaching is important,” Duncan had said. It was clearly important in this celebration of her life and art.

Two more dances came after the on-stage lesson, first, a cry of anguish entitled “Mother,” choreographed eight years after the accidental drowning of Duncan’s two children. The closing dance was a dramatic paean to the worker, “Revolutionary,” after Duncan became drawn to the communist movement in Russia.

Like the first two pieces, both “Mother” and “Revolutionary” were translated into descriptive poetry. The pain of Duncan’s loss as a mother surged through her arms, first cradling, then yearning. In “Revolutionary,” she danced a universal and idealized worker with images of struggle (arms thrust down on clenched fists;) outcry (a silent scream, framed with her hands;) and the call to resist (elbow drawn back, then thrust forward.)

Through both the teaching and her dancing, Gallant created a beautifully illustrated biography of Isadora Duncan, seen through an adoring lens. Duncan’s call is a century gone, but a new generation of students watched, learned, danced, and were enfolded.

copyright © 2019 by Martha Sherman