An Ever Green Evergreen

"Nutcracker"

San Francisco Ballet

War Memorial Opera House

San Francisco, CA.

December 11, 2019

The same old, yet forever new. Great art doesn’t tire you. But how many works, as awkwardly structured as the “Nutcracker,” is can make that claim? Yet this year, I cannot remember having been so grateful to Messrs. Tchaikovsky, Ivanov, Petipa and Helgi Tomasson. The latter’s 2004 “Nutcracker” was as close to immaculately performed as I can remember. Maybe, it helped that this year is the 75th anniversary of America’s first full-length performance of “Nutcracker” at San Francisco’s War Memorial Opera House. One of its attractions had come from the number of bright red costumes, made from discarded theater curtains. It was the war after all.

Tomasson’s production looks burnished, a little like the family silver people used to treasure year after year. The party guests, dressed by Martin Pakledinaz, looked as relaxed as they were elegant; the women in Edwardian pastel finery, the little girls in party dresses, their brothers and cousins in knickers and boots. Only the grand father (Jim Sohm) was befuddled by this newfangled invention of electric lights on the tree. And the photo ops at the end of a scene, reminded us that taking family pictures was not always a natural custom.

In a show with a fair amount of familiarity, Tiit Helimets’ Drosselmeyer stood out. Apparently, he had performed the role in one of the 2018 performances. New to me, he was the kindly uncle and a magician, a character with a sense of mystery about him. But Helimets outdid all of the Drosselmeyers I have seen. With his slightly swinging walk, open arms and delicate hand and finger gestures, he looked as if he had blown in from a different century. He was a much-welcomed guest, but clearly was an outsider. His graduated bow greetings carried a sense of courtesy in which gentlemen naturally bowed to each other and kissed ladies hands. Such a pleasure to see was Helimets’ finely detailed characterization of — who knows? — a voice from another era.

Max Cauthorn gave his clown a lovely touch of melancholy. A rag doll after his cartwheels, leaps and floor rolls, he pathetically tried to raise himself toward Lauren Parrott’s exquisitely stepping Doll. Her staccato footwork highlighted what he didn’t have: articulate feet. Hansuke Yamamoto, early in his career noted for his phenomenal leaps, has become a much more nuanced artist, but his Nutcracker Doll still had impressive elevation.

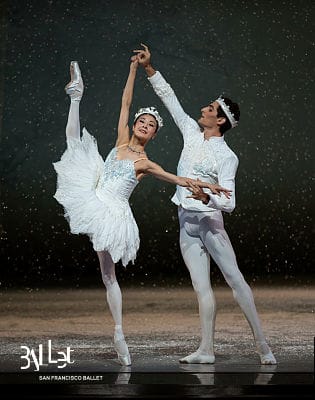

The intricacies of the Waltz for the sixteen snowflakes took advantage of just about every mathematical variation within that number. It surely must be one of the most intricately choreographed ballets blancs. Unfortunately, some of its patterns almost disappeared in what can only be thought of as a blizzard, maybe called up by Drosselmeyer. Yuan Yuan Tan, with Carlo di Lanno as her king, unfolded herself with such majesty and inborn gentility that it became easy to see why Tan, after twenty-three years with the company, still is SFB’s premiere ballerina.

The casting of the second act’s divertissements offered few surprises. Sasha De Sola’s Sugar Plum Fairy graciously accepted Luke Ingham’s large and spacious mime account of Clara’s bravery. (Ingham returned later in the Grand Pas de Due). De Sola’s cloud-like raising arms, shimmering point work and precisely timed turns were set in a pristine glass-enclosed planetarium, recalling one of the 1915 exhibition halls. For a long time, it looked too barren after the Stahlbaum’s warm and comfortable home. But time has proven Tomasson—and set designer Michael Yeargan—right. With just a few props suggesting the dances’ national origins, this simple set squarely focused on the dancing.

We got a Spanish quartet with clacking heels and whipping skirts. Kimberly Marie Olivier slithered out of the Arabic’s magic lamp, supported by two porteurs whose makeup came close to a parody. An impressively leaping Lonnie Weeks just about lost control of his multi-joined Chinese (student) dragon. In another bow to the local culture, Kamryn Baldwin, Maggie Weirich and Ami Yuki managed to keep their ribbon dance flowing, and still deliver some modest can-can steps. This French variation, still doesn’t convince choreographically. The one bow to the past, held over from an earlier SFB “Nutcracker,” is the Russian variation by Anatole Vilzak. Esteban Hernandez led his companions in its explosive leaps from Fabergé eggs.

In the Grand Pas de Deux, Mathilde Froustey and Ingham avoided bravura display, without neglecting the duet’s technical challenges. It seemed appropriate in a ballet that celebrates family and growing up. Despite a mishap, Froustey’s fine technique impressed with elegance and a touch of tenderness. Ingham, precise and musical, gave her the support she needed. Martin West conducted with great affinity for the music. This was no surprise, yet still appreciated.

copyright © Rita Felciano 2019